December 11, 2013 – In this final installment on Africa’s rivers and how climate change may impact the watersheds, biodiversity and human populations that rely on them, we look at Sub-Saharan West Africa including the Niger, Senegal and Volta river basins.

Although all of Africa’s rivers are vulnerable to rising atmospheric temperatures, the rivers that flow south from the Sahel region south of the Sahara Desert are probably at greatest risk. Of these the most vulnerable is the Niger.

Niger River – This river is home to more than 100 million and stretches 4,200 kilometers (2,600 miles) or the distance between Reno, Nevada and Baltimore, Maryland. That gives you some perspective on this river, the third longest in Africa. Its watershed touches ten countries. Like the Nile it flows through highly variable geography and many climate zones that are in stark contrast to each other. From tropical highland rainforests to desert, to farmland and urban centres, the Niger sees incredible diversity along its route to the ocean.

Uniquely the Niger forms two deltas, one inland and the other on the Atlantic coast. The inland delta forms as the river leaves its Guinea highland source and enters the western reaches of the Sahara Desert in Mali where it loses both speed and volume through massive amounts of evaporation. But as it winds and turns to the southeast it is eventually joined by a number of tributaries including the largest, the Benue, which restores water volume from its tropical rainforest sources. The river then descends to the Atlantic coast where it forms a second extensive delta, an area that covers 7.5% of Nigeria. Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city, lies within the Niger delta along the Atlantic coast. The delta is also Nigeria’s largest petroleum and natural gas production area.

So what will happen to the Niger in a world experiencing climate change? One can expect a similar outcome to other areas within Africa including reduced precipitation and river water volume. Already the river in serving the 100 million who live close to or on its banks is severely water stressed.

Climate models indicate changed weather patterns from increased greenhouse gas levels. The Niger will experience drier wet seasons and wetter dry seasons as temperatures increase. Since the early 1970s the Niger River basin has seen precipitation levels drop between 10 and 30% depending on climate zone. At the same time river volume has declined between 40 and 60%. Part of this can be blamed on extensive damming of the river at several locations. The Sahel and Western Sahara sections of the river may run dry should trends continue while the lower river experiences flooding from intense periodic rainstorms which the models are also predicting. Growing desertification in the northern part of the river basin is expected as well putting further pressure on scarce water resources.

Senegal River – This 1,790 kilometer (1,100 mile) river lies north and to the west of the Niger. It flows through four west African countries – Guinea, Mali, Mauritania and Senegal. Heavily dammed, the river is being exploited for both its hydroelectric capacity as well as a water resource for agriculture. Rain fed and originating in the Guinea highlands, the Senegal experiences highly variable seasonal distribution of precipitation and water volume with flows 300 times greater during peak precipitation periods.

A strategic action plan called the Senegal River Basin Climate Change Resilience Development Project is focused on climate change adaptation looking at how the countries of the basin will coordinate efforts to ensure sustainability beyond 2100. This plan is being funded in part by the World Bank and looks at land degradation, desertification, saltation, overgrazing, bush fires, water quality, proliferation of invasive species and waterborne diseases, and threats to biodiversity. Climate change mitigation measures include managing waste discharge to protect water resources for human consumption and wildlife, flood protection zones, epidemiological monitoring of waterborne diseases, forest and aquaculture restoration, corridor zones to assure wildlife diversity, and capacity building to ensure that the local governments can continue to sustain the river basin without outside assistance. It is an ambitious project but the Senegal River, the most intensively developed in West Africa, is an excellent candidate for such a project and should ensure its sustainability into the 22nd century.

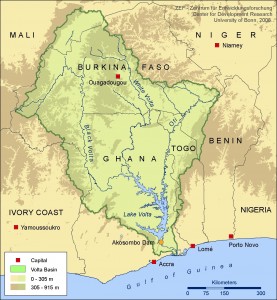

Volta River – This 1,600 kilometer (1,000 mile) river lies largely within one country in West Africa, Ghana. Its twin source tributaries, the White and Black Volta originate in the highlands and mountains of neighbouring Burkina-Faso. In a study released last July, climate change models indicate that by 2100 much of the river basin will be under severe water stress impacting agriculture, power generation and freshwater for drinking.

Temperatures are expected to rise by as much as 3.6 Celsius (6.5 Fahrenheit) degrees in the river basin with significant increases in evaporation and reduced river water volume. Volumes will diminish 24% by 2050 and 45% by 2100 according to the models. The population of the river basin is expected to top 34 million by 2015. That represents an 80% growth since 2000.

The river features the world’s largest human-made lake, Lake Volta, rising behind the Akosombo Dam. Other dams have been constructed for power generation but as water volumes fall in the face of climate change power generation capacity is expected to decline.

A Final Note

This three-part look at Africa’s river basins from the perspective of climate change is meant to give you some perspective on the impact greenhouse gas emissions will have on an area of the world that is not a primary emitter of CO2. Africa will once more be a victim of the Developed World’s exploitation of the planet’s resources. And other than contingency planning to deal with the consequences of what we have already put into the atmosphere to date, we have only this, to ensure that we can mitigate the worst and reduce further greenhouse gas emissions so that what we project as the worst remains just that.