In 2007 New York City released a plan entitled PlaNYC. It focused on the future sustainability of the city and included a section dealing with climate change. The key points focused on increasing the resilience of the city’s built and natural environments by:

- Developing strategies to encourage the use of flood protection in buildings.

- Protecting New York City’s critical infrastructure.

- Identifying and evaluating city-wide coast protective measures.

- Recognizing the potential destructiveness of coastal storms combined with the rise in sea level.

New York recognized not just waterfront property would be impacted by climate change and weather events. Flooding could immobilize 700 miles of subway, impact the 90,000 miles of underground power cables, compromise 14 wastewater treatment plants, and potentially cause a transportation nightmare if any of the 2,000 bridges and tunnels were damaged. All this infrastructure was immovable and a storm could make it vulnerable to massive disruption.

Enter Hurricane Sandy, a Category 1 storm that tested the city and its neighbouring shorelines like no other before it. Today in the aftermath of Sandy, the Atlantic coastline that includes New Jersey, Long Island and New York City is faced with a herculean task.

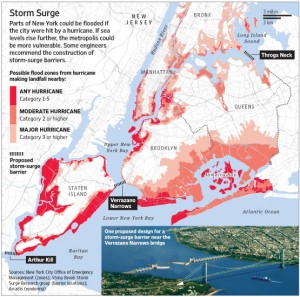

How do you prevent another storm from wreaking damage ($50 billion estimated so far) equal to or even greater than Sandy? If Sandy, a Category 1 hurricane could do this imagine what a Category 2 or 3 could co and then consider what kind of infrastructure would be needed to deal with such destructive storms.

What are the forces of nature we have to fight to keep the Atlantic Ocean at bay?

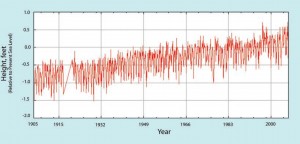

- Rising sea levels – In 2007 the IPCC projected global sea level rises of between 0.2 and 0.5 meters (approximately 8 to 20 inches) by the year 2100. But recent evidence according to the Geological Society of America is suggesting the projections are too low. Revisions suggest a high end of close to 1 meter (39 inches). So whether we take the low ball number or the revised number we are looking at higher water. See the graph below showing New York City harbour data on rising sea levels. It’s an eye opener.

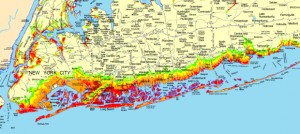

- Storm surges and Local Geography – New York City sits at the apex of a funnel. A storm coming from the southeast will push Atlantic Ocean water into this narrowing space aided by a shallow and wide continental shelf. In addition, much of the shoreline is primarily composed of loose materials including sand, gravel and clay, all easily reworked by wind and water. Factor in all these characteristics and you have a recipe for a Sandy to do its worst.

- Storm Frequency Changes – In the last century the frequency of Atlantic hurricanes has doubled. Climatologists conclude that warmer ocean surface temperatures and altered wind patterns are the cause. Between 1900 and 1930, we averaged 6 tropical cyclones (not all at hurricane strength) per year. The frequency between 1995 and 2005 has reached an annual average of 15. Between 1900 and 2005 tropical ocean surface temperatures in the Atlantic have risen by 0.7 degrees Celsius (1.3 Fahrenheit).

- Storm Intensity Changes – Hurricane Sandy was a Category 1 when it struck the Jersey Shore. Hurricane Hazel which tracked over a similar path in 1954 was a Category 3. Hurricane Donna in 1960 was a Category 1 by the time it reached Long Island. So intensity seems to be highly variable with no correlation to rising ocean surface temperatures.

With Sandy it was much more than intensity, it was the immensity. And now this area has to rebuild. What should be done? Here are a number of initiatives that can harden the area to future storms and storm surges.

- Long Island and New Jersey need to re-engineer their shorelines to build them up to withstand Atlantic storms and rising sea levels.

- Flood gates need to be built on the approaches to New York City to counter storm surges

- New York City needs to develop flood defenses to ensure its infrastructure is not compromised.

- Buildings in coastal cities in New York and New Jersey need to develop self-sustaining capability to withstand a blackout from the grid going down.

Re-Engineering the Shoreline

Because of the nature of the material content of the New Jersey, Staten Island and Long Island shorelines beach replenishment is a non-starter. Just piling sand on top of the areas eroded by storm surge will do little to ensure the durability and duration of any repair. Not only that, the cost of pumping sand up from offshore where the hurricane dumped it can be quite prohibitive. Once you start down this path it becomes an ongoing exercise.

Another traditional coastline rehabilitation technology is the building of groins (seen below) and jetties. Although successful as sand traps they prove to be ineffective against storm surges turning shorelines into obstacle courses.

The most commonly used defense for storm surges includes the building of seawalls and levees. It was poorly maintained levees that allowed Katrina’s storm surge to flood New Orleans. Properly built and maintained they would have prevented that Category 3 hurricane from inundating much of the city. A series of seawalls on Long Island, Manhattan, Staten Island and the Jersey Shore all failed during Sandy. They were not built high enough or strong enough to withstand the storm surge. If rebuilding of the walls is to be done, engineers may want to consider defense in depth with a combination of berms or levees and well anchored taller walls.

At best any beach shoreline re-engineering will prove a temporary fix as a line of defense against storm surges. It is the price of building on shifting sand.

Flood Gates

With 75% of the world’s population expected to be living in coastal communities by 2025 a more effective technology solution, than those described above, for combating rising ocean levels and storm surges is very much needed. And yet there are plenty of good examples of a technology that works already in place – flood gates. The Dutch have been building them for years allowing them to reclaim hundreds of square kilometers of land from the North Sea. The Thames River gates stave off potential flooding of London. Venice has been building new flood barriers to stop the Adriatic Sea from further damaging the city. Flood gates control the flow of the Mississippi River. And even New Orleans has them now to protect it from storm surges. So why not New York?

The cost of such a project is estimated at $15 billion, less than one-third of the estimated cost for cleaning up the damage caused by Hurricane Sandy.

City Internal Defenses

One proposal that has come out of Hurricane Sandy includes the development of a giant inflatable plug that looks like something out of a Woody Allen comedy. You can see it in the picture below.

The plug is just under 10 meters in length (32 feet) and 5 meters wide (16 feet). It can be inserted deflated into a tunnel opening and then quickly filled with water to effectively seal it off. Made from Vectran, a liquid-crystal polymer fiber, several could be placed in strategic locations to protect subways, roadway tunnels and other vulnerable sub-structure. Each costs $400,000.

To protect smaller underground accesses such as ventilation shafts technology can be designed to automatically seal entrances in the advent of a storm surge, further protecting New York’s infrastructure from flooding.

Building for Off the Grid

Urban living is heavily reliant on the energy grid. When it goes down it’s more than lights out. Elevators are inoperable. Appliances no longer work. Water pressure falls and without supplementary pumps is no longer available to apartment dwellers. Add to this the loss of transit like subways which rely on electricity and you have a pretty dysfunctional urban setting. That’s why cities like New York need to develop sustainable energy technology for high rise buildings in the event of a prolonged loss of power from the energy grid.

This can be accomplished using renewable energy sources like solar and wind. Apartment waste can be converted to energy using small cookers to heat water to drive turbines. Apartments could be outfitted with supplementary battery storage to cover the gaps when the sun is not shining or the wind not blowing. This would ensure continuous power for operating essential services such as elevators, air conditioning, common area lighting and water pumps.

Some buildings today in New York City are installing Otis “Gen2” elevators that use 75% less energy by feeding energy recovered from braking during descent and feeding it into the building’s internal electrical grid. Other innovations include blue roofs designed to capture rainwater for use in sanitation. A typical New York building outfitted this way could capture thousands of cubic meters of water for lots of low-flow toilet flushes.

Build seawalls

Move inland more

build storm barriers 30-90 miles out

build canals to take water inland or to lakes

Live away from beaches

Build offshore sea cities in LI Sound & off Staten Island for populace.

Move Manhatten commerce to Albany or Pittsburgh , away from Manhatten Island area.

Estd backups for Manhattten business, telecomm etc.

build artifical reefs to stem storm surges

OK wind farms near LI & Staten Island area for power

Acess Manhatten by RR, subway, bus & remove cars from Island.

Make Hwy connecting LI to Manhatten cutting through Harlem.

& more

Tear down older bldgs or house under domes or enclosures for Historic value.

After the hurricane sandy there are a lot of things to rebuild, refurnish and rebuilt. It has caused many buildings and subway flooded with water. This giant inflatable plug was a good idea. Though, there are still subways that was reached by the water. We should be aware now that our climate has changed and we should always be alert whenever there is typhoon.