July 24, 2014 – I don’t know about you but I’ve been wearing prescription glasses since I was seven years old. I’ve tried contact lenses several times and given up on them. I’ve contemplated laser vision correction but have been told that my astigmatism would make it less than effective. And at my age today I wear progressive trifocals regularly and progressive bifocal computer glasses when I am writing this blog. So you can imagine my interest in an article that describes a new display technology that alters images it projects to those watching to adjust to their individual vision.

How does it work? Using algorithms to alter imagery based on your eyeglass prescription, the pixels in the display get re-oriented to create a sharp image for the viewer. You can be near or far-sighted. It doesn’t matter.

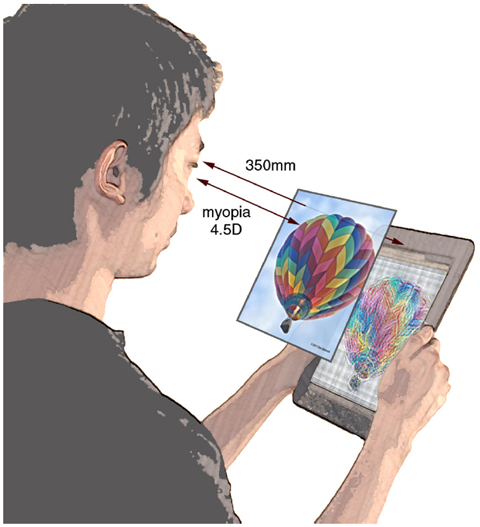

The technology comes from University of California, Berkeley and is being developed in collaboration with Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Microsoft. To create a perfect image for viewers who normally wear prescription contacts or eyeglasses, images are warped and then passed through a screen filter pierced by thousands of evenly spaced holes (see the picture below). This controls individual light rays emanating from the display and provides a sharp image with no loss of contrast.

To test the technology the inventors, Brian Barsky and Gordon Wetzstein, have used a digital camera with its focus set to simulate a range of vision problems. They still have a lot of work to do to get the technology beyond prototype. For example right now the technology requires the person to keep his or her head still. That won’t do. We move our heads all the time when watching a screen. So the the software needs to adjust the image to new perspectives based on viewer head movement behavior.

Also, the technology is one-on-one. You can view it or I can view it but not both of us at the same time. For it to be commercially viable it needs to simultaneously correct for many viewers at once regardless of their prescription. The researchers believe both problems are easy to fix by software additions and by improving pixel density.

A paper describing the results will be presented at Siggraph 2014 in Vancouver, British Columbia this August. Siggraph is known for being the forum for announcing latest breakthroughs in computer graphics research.

When will we see the commercial results? In several more years say the inventors.