An article in today’s Globe & Mail by Shaun Pett got me thinking about our heavy reliance on annual staple crops to feed the world and the cost we bear because of this. Annuals are labour intensive. They involve plowing the soil every year and seeding. They are responsible for 70% of the food calories we humans and our animals consume. And their management and cultivation contribute to greenhouse gas emissions amounting to 24% of the total.

In the article Pett states that we fell into this trap 10,000 years ago at the dawn of the Neolithic when we chose annual grains, legumes and oil seed crops to be our main source of plant nutrition. The result today is agricultural practices that are problematic with Pett in his article providing some statistics and challenges that we face because of our reliance on annuals:

- today 70% of the food calories we consume come from these types of crops;

- growing annuals for food contributes 24% of the greenhouse gases we produce globally;

- deep plowing for planting annuals contributes to soil erosion;

- or the alternative no-till planting requires lacing soils with enough chemicals to inhibit weeds and competitive plants.

At the Land Institute in Salina, Kansas, researchers are looking at ways to alter our dependence on annuals by developing perennial versions of the plants we grow for food. For years I have planted a perennial garden rather than annual flowers. I have done this even at our new apartment downtown here in Toronto, planting perennials in pots rather than the typical flowering annuals. Why? Because perennials seem better equipped to handle environmental changes. They persist under the most difficult conditions. If it is too cold in the spring they tend to be self inhibiting waiting for the weather to improve. And they seem to be less demanding about soil conditions or needing artificial fertilizers. A good mulch cover in the fall works wonders.

The researchers at the Land Institute believe that perennial grains, oil seed crops and legumes can be developed reversing 10,000 years of agricultural mistakes made by us. They are doing this in two ways:

- discovering wild perennial plants with the best crop potential and domesticating them;

- or cross-breeding annuals with related perennials to create new hybrids.

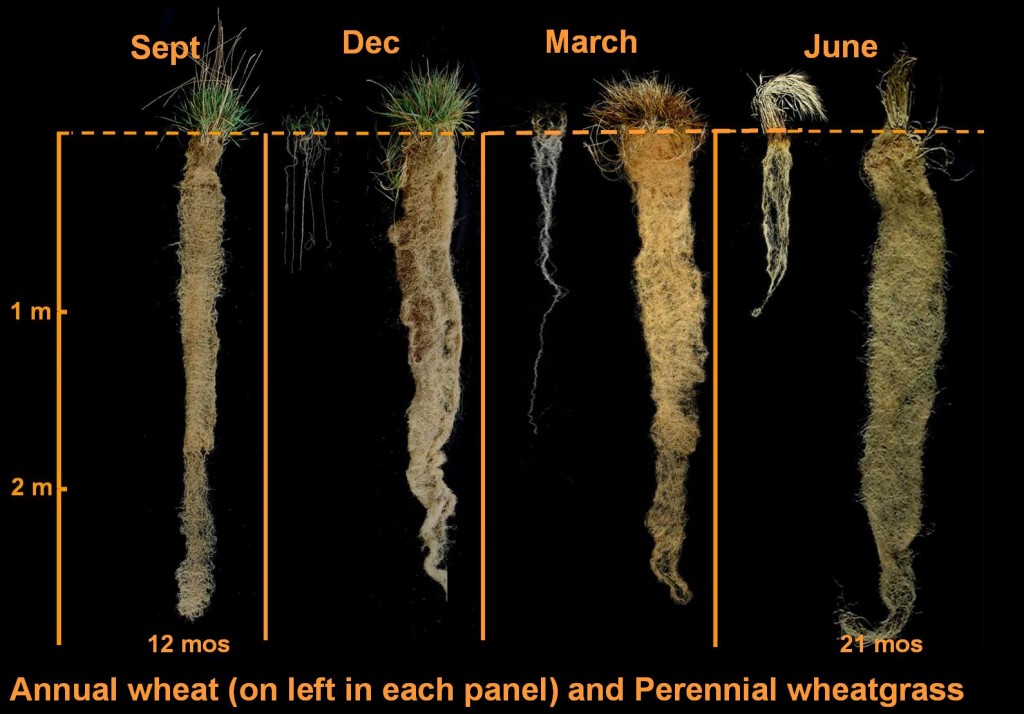

The hope is to release the first perennial grain crop within a decade. The Institute is currently developing a wheat grass called Kernza. It looks a bit like wheat but like most perennials it grows more slowly. It develops extensive root systems (see image below) which hold the soil in place and retain moisture. It shows high variability when planted so a Kernza field isn’t as pretty as the wheat fields you see on the Prairies today. But it provides continuous coverage so the soil is not exposed to erosion. It needs less tending and as a bonus provides winter fodder for native and herding animals without losing its viability to propagate and produce subsequent harvests.

The Institute has been developing Kernza for 7 years and has harvested the crop to produce flour “excellent for use in biscuits, cookies, crackers, and muffins.” The yields to date are far less than those produced by annual wheat but the researchers believe they will soon match wheat in future harvests.

And Kernza is proving to have other unique benefits. Its protein content per kilogram is 20% higher than wheat. It produces more fibre, double the level of omega-3 fatty acids, five times the calcium and ten times the folate.

Other perennial projects at the Institute include development of a perennial variety of sorghum as well as perennial sunflowers.

Is the Institute unique in pursuing perennial crops? Hardly. We’ve been growing them as food sources for years. After all fruit and nut trees, bananas, palms, breadfruit, and avocados are all perennials. Several types of perennial beans and tubers provide staple crops for many tropical and subtropical countries. But none of the above equal the volume of food we get from grains like wheat and rice, two of the dominant agricultural crops grown on this planet. We can, however, learn from our experience in cultivating perennials, ways to develop even more choices and in the process reduce the toll we are putting on precious top soils and fresh water while feeding the planet.