April 28, 2015 – Are extreme weather events the “smoking gun” of climate change? Back in July 2012 I wrote a posting entitled, “Weather Extremes and Global Warming – Are they one and the same?” At the time I stated “it’s important not to associate today’s weather with the bigger hypothesis that espouses global warming.” Well in a study appearing in Nature Climate Change this month, the authors, Erich Fischer and Reto Knutti, from Zurich’s Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, challenge that lack of association, correlating heatwaves and heavy precipitation events to human influences.

In their study they state that “today 75% of the moderate hot extremes and about 18% of the moderate precipitation extremes occurring worldwide are attributable to warming, of which the dominant part is extremely likely to be anthropogenic.” That means the balance are not causally linked to what we humand are doing to the planet. Think about that. For every four extreme heat events three are anthropogenically derived. And almost one in five extreme weather events can be linked to anthropogenic causes.

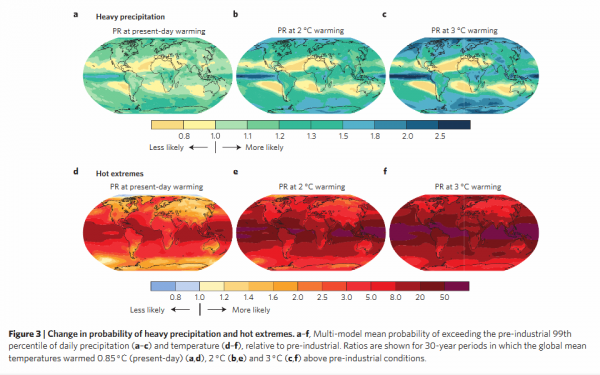

The authors link present day warming of 0.85 Celsius (1.53 Fahrenheit) and increasing extreme precipitation events as exceeding pre-industrial occurrences by a small margin. But when they project the trend to a warming of 2 Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) the link increases by a 1.5 to 3 times factor depending on location on the planet. Worse in the tropics and in extreme polar locations and weaker in the mid-latitudes.

They write, “this implies that on average…an event expected once every 10,000 days (about 30 years), in pre-industrial conditions, is expected every 10 to 20 years at a 2 Celsius warming.” There is a similar correlation with extreme heat events. The authors state, “the trend to more hot extremes with increasing global temperature is ubiquitous. Already at an observed warming of 0.85 Celsius the probabiliyt of 1-in-1,000-day hot extremes over land is about five times higher than in pre-industrial conditions.”

For the “I’m not a scientist” crowd the study states that that quantifying the human contribution to a single weather event is challenging, but when you analyze the massive amount of observational global data you remove the uncertainty. The authors use sophisticated modeling of the data to draw their conclusions and although models aren’t the real world, they are an attempt to simulate it as closely as possible.

It is hard to argue with the wealth of sampling the authors have used to build their hypothesis. Nor can you argue with their motive. They hope policy makers can use this as a tool for mitigation and adaptation decisions. When combined with maps the data can serve to show actual risk and vulnerability. The authors state “the fraction of heavy precipitation and hot extremes attributable to warming is highest over the tropics and many island states, which typically have high vulnerability and low adaptive capacities.”

The maps appearing below come from the study. Areas of greatest vulnerability are highlighted.