July 20, 2014 – If you work for the post office these days then you already have an inkling of what the 21st century will do to many jobs. Texting, email, and mobile connectivity have forever altered the way we communicate. How many of us still write letters on paper and mail them?

Back in September of 2013, Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne, of Oxford University, published a paper entitled The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerisation? They looked at artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics and the potential impact that advances in these two fields would make on 702 different occupations.

They cited other studies that looked at software technology advances and the attendant labour disruption in manufacturing. And they cited published works that pointed to a future of autonomous driverless transportation. In the former case computerization (the word being used to collectively represent both AI and robotics) was altering the labour component on assembly lines. In the latter our driving future, one of the most common rites of passage we humans learn as we approach adulthood, may soon vanish. Imagine what taxicab, transport truck and bus drivers are thinking when they read about autonomous computer-driven vehicles?

We are not the first humans to experience technological advances that have altered employment patterns. Disruptive technologies have always produced creative destruction in labour. The spinning wheel and later the loom altered cloth manufacturing forever. Typists on typewriters replaced scribes and stenographers? Assembly line manufacturing eliminated cottage artisan industries. And large-scale manufacturing facilitated rural to urban migration which today is happening at an increasing pace everywhere in the world.

Cities are where jobs are found. Workers congregate to do collective tasks. And where workers congregate so do those who provide services to meet their Maslowian needs. The concentration of humanity in urban settings continues to inspire disruptive innovation that is creating whole new classifications of jobs and work for millions. And although it remains true that no individual wants to experience having the skill set they acquired in life declared obsolete, this continues to happen and at an increasingly faster pace in the 21st century.

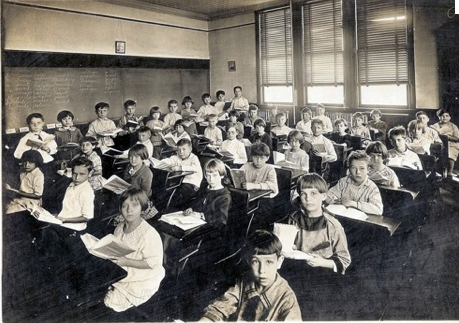

Our current educational system is today experiencing the tensions that disruptive technologies are inflicting on it. I grew up in a 19th century industrial model of education. The primary and secondary schools I attended were assembly lines for cranking out a workforce for 20th century jobs. I took typing because office jobs required it. I studied geophysics and history in university thinking I’d be a high school geography and history teacher but when I graduated there were no job opportunities in either of those subject areas.

Today teachers are feeling the change that computerization is having on education. Rote learning and times tables are being replaced by software and search algorithms. Students who know how to ask Google questions can learn more in an evening of search then in a week of classroom lectures. Libraries, once the physical repository of all knowledge, are moving to the Internet Cloud where even obscure journal articles can be called up during a search.

My typing skills came after I learned to write in cursive script. Young people, however, struggle with handwriting and penmanship because until they have to sign a cheque, contract or letter, they don’t manually write. And this skill which dates back to the dawn of our human civilization may completely disappear in the digital age.

Our politicians talk about the current threat to the middle class, the hollowing out of our modern societies, and the concentration of wealth in the hands of the few. But what they don’t point to is the root cause. What is it? The pace of change and disruptive innovation with computerization as we have defined it here, a significant contributor to all of the above.

So who will and who will not work as the 21st century unfolds? In a recent New York Times Sunday Review, Steven Rattner writes about the coming of robots and future jobs. He provides two charts showing technology’s transforming influence. On one side he lists occupations in decline betwen 200o and 2013. On the other side he lists growing professions during the same period.

Here are some examples of jobs in decline:

- Word processors and typists have seen a job decline of 74% with 287,000 jobs lost at an average median wage of $35,270 (US 2012).

- Travel agents have seen a 46% decline in jobs representing 65,000 at an average median wage of $34,600.

- Bookkeepers have seen a 29% decline in jobs representing 501,000 at an average median wage of $35,170.

Here are some examples of jobs in ascendance:

- Computer and systems managers have seen a 164% increase in jobs representing 374,000 at an average median wage of $120,950.

- Financial managers have seen a 28% increase in jobs representing 270,000 at an average median wage of $109,740

- Accountants and auditors have seen a 16% increase in jobs representing 255,000 at an average median wage of $63,500.

What these statistics reveal is that disruptive technology is altering what we need to know to be successful in the 21st century, and that the types of jobs and earning rewards attainable by riding this wave of constant change and creative innovation is well worth the end reward.

In my recent talk to the Jamaica 2030 conference under trends in robotics and AI I listed the 2 billion jobs on this planet that will disappear by 2030. I share the content of two of these slides here:

- In Energy as trends move to renewables, off grid and micro-grids we will see jobs disappear in mining and extraction, transportation, grid utility maintenance, pipelines, and railways.

- In Transportation as trends to smart highways, autonomous EVs, more mass transit and on-demand systems in place jobs will disappear for truck drivers, delivery companies, taxis, bus drivers, limo services, gas station attendants, and automobile and truck manufacturers.

- In Learning as education moves to the cloud jobs will disappear for teachers, trainers, and librarians.

- In Manufacturing as additive technologies replace traditional processes jobs will disappear in construction, forestry, quarrying, concrete, assembly line engineered products, clothing manufacturing and retail sales.

- In Agriculture, Fisheries, Mining and the Military with robots replacing workers there will be fewer farmers, fishermen, miners, soldiers, and construction and manufacturing workers.

In those same fields where will we see new jobs?

- In Energy we will see new jobs for micro-grid operations, national grid conversion, solar, wind, tidal and wave engineering and installers, hydrogen engineers and infrastructure developers.

- In Transportation we will see new jobs for smart sensor designers and developers, automated traffic engineers, software architects for autonomous systems, and maintenance and emergency workers.

- In Learning we will see new jobs for courseware designers, search algorithm creators, mega data analysis tool designers, and personal learning coaches.

- In Manufacturing we will see new jobs for additive manufacturing materials developers, 3D printing engineers and 3D printer maintenance.

- In Agriculture, Fisheries, Mining and the Military we will see new jobs for robot designers, AI coders, robot coaches and trainers, and robotics repair.

Frey and Osborne list where we humans still have machines beat. In the three areas they cite I agree with two but not the first. They list first our advantages in perception. As I have recently written autonomous vehicle technologies are proving that we may soon lose our lead with advances in computer vision and AI. But on the latter two I am in full agreement. They are:

- Creativity

- Social Intelligence

In creativity we maintain a huge lead over our robotic and AI technologies. We humans are a fount of ideas. We are creative problem solvers. We write novels, compose music, produce dance, art, sculpture and drama. We are the original thinkers.No AI system can match us in this area.

In social intelligence there is no AI rival that can challenge our skills in negotiation and persuasion. No algorithms can match our nuanced ability to judge body language in interacting with other humans. No AI can match our empathy and emotional support in working with coworkers, clients or those requiring personal healthcare.

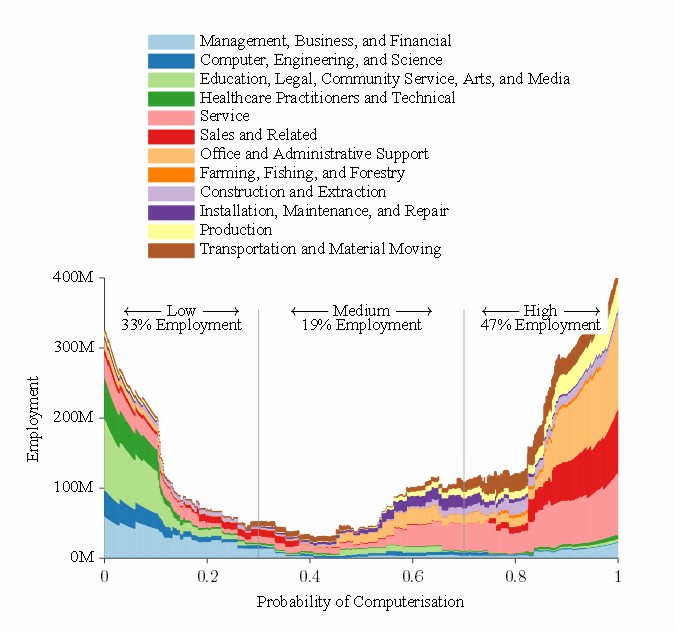

Frey and Osborne provide a graph showing probability of computerization related to future employment across a range of industries. It reinforces much of what has been described in this post.