What part have pandemics played in history? Kyle Harper, a Professor of Classics at the University of Oklahoma, published a book entitled The Fate of Rome in which he described the 2nd Century CE Antonine Plague that devastated and depopulated the Mediterranean world leading to a prolonged period of migration of populations from outside it destabilizing the empire into the late 3rd century.

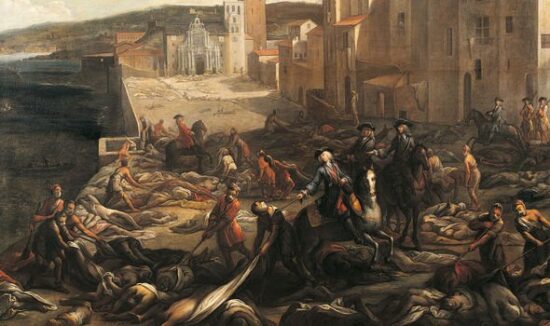

Well, something similar happened in the mid-1300s and we know its name from the history books: The Black Death. Also called the bubonic plague it began in Asia and arrived in Europe seven years later. But up until now, we didn’t know from where the Black Death originated.

Modern science, however, has unravelled the mystery of the pandemic that lasted from 1346 to 1353 CE (AD) in the first wave. An article appeared last week in the journal Nature, entitled “The Source of the Black Death in Fourteenth-century Central Eurasia.”

The Black Death was caused by a bacterium, Yersinia Pestis (Y. Pestis). Searching for the bacterium, not its evolved variants, took paleogeneticists to northern Kyrgyzstan in Central Asia where unearthed plague victims were found to have traces of the original Y. Pestis DNA. It is likely the disease emerged even earlier, by as much as a century before it marched across Medieval Europe.

Without antibiotics or any understanding of how the disease spread, The Black Death wiped out between 30 and 50% of Europe’s population. It got its name from the spots that appeared on those who were infected. The name bubonic plague refers to buboes which were painfully swollen lymph nodes that bulged. The Black Death infections included other symptoms such as delirium, high fever, and vomiting.

The key to uncovering the origin relies on evidence from three women who were buried near Lake Issyk Kul on the edge of the Tian Shan mountains. They died in 1338 and 1339 of what was referenced on their grave markers as a pestilence. Nearby were many more grave markers covering the decade before The Black Death arrived in Europe.

Y. Pestis was a bacterium that resided in fleas which then past it on to animals and humans through bites. Rats were seen as the likely source of Europe’s outbreak. But humans were facilitators of the spread along trade routes from Central Asia to Europe. What we do know is that the original strain of Y. Pestis mutated into four variants with one of those arriving in Europe seven years after the Kyrgyzstan outbreak.

The parallels to today cannot be missed. The Black Death has never gone away in almost 600 years since its first appearance. It has evolved and although it is treatable by antibiotics still persists with outbreaks making the news from time to time. The four variants still represent 40% of the current Y. Pestis bacteria and can still be found near the Tian Shan mountains in Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and the Xinjian Uygur Autonomous Region of Northwestern China.

This latter fact should be noted by those studying the emergence and persistence of COVID-19. The pandemic virus that has currently travelled around the world has undergone a Greek alphabet of mutations with each new variant more transmissible than the previous ones.

Fortunately for us, unlike in the Medieval World, we have mapped the virus variant genome, and created vaccines and medications in record time to try and minimize its damage.

We have a new set of investigative tools for historians today. These are called phylogeography and metagenomics. Both are changing how we explain the great trends of history that formerly were subject to conjecture, or explanations focused on warfare and migration. Now add biological evidence and paleoclimatology to the mix. The study of ancient and medieval history has never been more interesting.