April 20, 2016 – At the United Nations this Friday, Earth Day, 150 nations’ representatives will sign the Paris climate agreement. But signing an agreement with good intentions doesn’t amount to much more than a gesture. That’s because the agreement has no teeth, just the promise that the signatories are committed to the effort to keep temperatures from rising above 2 Celsius with a further effort if possible to not exceed 1.5 Celsius.

But anyone looking at national carbon reduction commitments and doing the math can quickly figure out that the results will not meet these temperature targets. It is far more likely that we will see by mid-century mean average temperatures rising more than 2 Celsius.

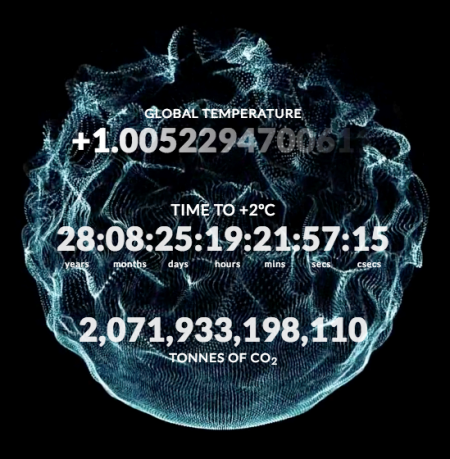

Documenting that rise is the Countdown 2 Degrees clock that already shows we are half way there. We certainly will surpass 1.5 Celsius by 2030 if we remain on our present course. That’s because almost all nations have set carbon reduction targets that roll back greenhouse gas emissions over these next 14 years to levels approximating those in the first decade of the 21st century. Those levels of output exceed the natural capacity of our ocean, forest and soil carbon sinks and mean CO2 levels will continue to rise. To call the 2030 targets unrealistic, therefore, is an understatement. In fact, the emission cuts will achieve about 1% of what is needed leaving those after 2030 with the much bigger challenge.

So what is needed?

A “damn the torpedoes” mentality to build green energy and implement green policies globally starting with a carbon tax to act as an inhibitor to the non-green practices of current economies. The investment needed in research and development (R&D) should be akin to running several Manhattan Projects in parallel and over decades.

Bill Gates, the founder of Microsoft and wealthiest man in the world, argues the need for the combined push and pull strategy of a carbon tax plus a hefty dose of R&D. In a recent The Atlantic article entitled, We Need an Energy Miracle, he indicates his own personal pledge to commit $2 billion to the R&D cause.

He criticizes the outcomes of COP21 pointing out they “are not binding” and “fall dramatically short of the reductions required to reduce CO2 emissions enough to prevent a scenario where global temperatures rise 2 degrees Celsius.” He further argues that “everything that’s hard has been saved for post-2030” in referring to the less than dramatic commitments made by world nations in Paris.

His reasons for implementing a carbon tax are simple arguing “without a substantial carbon tax there’s no incentives for innovators or plant buyers to switch” from existing energy sources. Compounding the problem is the length of time needed to bring new energy technologies from the laboratory to commercial scale. Gates states, “almost everything that’s been invented in energy was invented more than 20 years before it got scaled usage.” Twenty years from now puts into the year 2036. So doing R&D at current levels of spending whether from government or private sources isn’t going to cut it.

Gates points out that the American annual energy R&D budget equals $6 billion per year. He would like to see it immediately tripled and just to fund basic R&D. The mechanism to find the money could come from carbon and energy consumption taxes. He states, “this is not an unachievable amount of money.”

Gates feels that funding many ideas in parallel is the way to go. He says, “we want to give a little bit of money to the guy who thinks that high wind will work; we want to give a little bit of money to the guy who thinks that taking sunlight and making oil directly out of sunlight will work.”

Gates argues that not just governments should be investing in the R&D to combat global warming. Government may be the initiator of a particular R&D but unleashing the private sector to implement successful laboratory outcomes will help to get us “beyond the CO2-based energy economy.”

For Gates he views what we collectively are doing today as a “2-degree experiment.” His concern is if we don’t get it right in the next 15 years then we will be running the “3-degree” or the “4-degree experiment” and we haven’t a clue what kind of and the cost of adaptation strategies in these latter two scenarios.