May 5, 2020 – The world is 1.1 Celsius (1.98 Fahrenheit) degrees warmer on average than it was in 1950 according to the latest data collected by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). This is a mean average increase. Has the rise made any parts of the world uninhabitable for humanity as of yet? It’s a near thing in some parts of the world with places in Pakistan, India, and Iran hitting 50 Celsius (122 Fahrenheit) or higher in the last couple of years.

In central Australia, in areas of the Middle East, the Sahara Desert, and on some asphalt-covered city streets, it is not uncommon to see summer daytime high temperatures exceed 50 Celsius. Asphalt melts and the human population abandons the streets when the temperature reaches halfway to the boiling point of water.

These types of temperatures are toxic to humans. Our cell function diminishes. Our bodies try to release moisture to cool down but in many cases, the atmospheric heat is compounded by high humidity interfering with our natural cooling apparatus. We don’t even need to hit 50 Celsius in high humidity for our bodies to be compromised. A web-bulb temperature of 35 Celsius (95 Fahrenheit), one that combines the metrics of both heat and humidity, is a killing combination. Yet today around the world, more than 350 of our cities are seeing average summer daytime high temperatures that exceed 35 Celsius.

In a paper published yesterday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), researchers from the Nanjing University (China), Washington State University, University of Exeter, Aarhus University (Denmark), and Wageningen Univesity (The Netherlands) describe how current trends in the growth of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions without climate mitigation will leave us with a world by 2070 where living conditions for between one to three billion of us will be severely compromised. It will render entire sections of our planet as uninhabitable for our species.

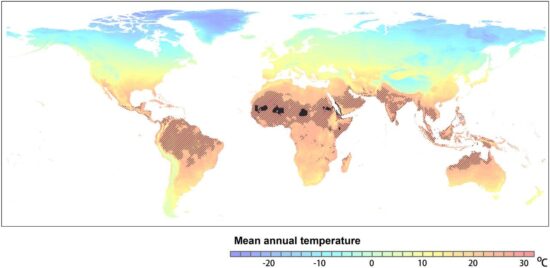

The authors define humanity’s natural climate niche as a mean annual temperature of approximately 13 Celsius (about 55 Fahrenheit) and consistent for the past 6,000 years. Many of you may think 13 degrees seems awfully low. But remember, this is a weighted mean average temperature across the entire habitable area of the planet. The weighting includes diurnal and seasonal temperature changes. This is what defines our human optimal environmental niche. The 13 degree Celsius mean temperature also refers to where the crops and domestic livestock we grow and husband can thrive. This is the human habitability zone for business-as-usual. Any place beyond the zone exists for us because of our technology. That’s where HVAC systems make it possible for us to live in the hottest deserts, the coldest polar regions, and at extreme altitudes. But we cannot apply HVAC technology to the great outdoors.

The authors describe what is likely to happen in the absence of climate change mitigation noting that temperatures by 2070 will be 2.3 times the mean global temperature rise of the last three centuries or as much as a mean increase of 7.5 Celsius (13.5 Fahrenheit) on land. If that number seems high, the weighted mean increase of 3 Celsius (5.4 Fahrenheit) across the globe takes into consideration temperatures over our oceans. And since we don’t live on the ocean, or under it, the 7.5 Celsius is the right number in the redefinition of our future habitable zone.

What this means is that places currently at a historical mean of 13 Celsius will in fifty years rise to 20 Celsius. Canada should fair well in this scenario without mitigation. But for places today hotter than the 13 Celsius mean where 3.5 billion of us live today, it means temperatures will rise to a mean 29 Celsius (84 Fahrenheit). Currently, a portion of the Sahara reaches that mean temperature representing a mere 0.8% of the planet’s land surface. But in 2070, that temperature regime will cover 19% of the world’s landmass.

In the absence of mitigation, migration is the likely response to these rising land temperatures. Predicting the climate-driven redistribution of our human population, however, is not a simple task. Warming will not be uniform, very much the way it is distributed today, and it is likely that migration will move in waves and pulses responding to rising heat, increased droughts, and extreme weather events. Add to these factors the changing vectors for tropical diseases that will migrate right along with rising temperatures and you have a very complicated scenario that will more than likely lead to conflicts and increasing death rates.

The redistribution of humanity as seen by the authors of this study will become our greatest challenge in the mid to late 21st century, that is, if we make no concerted effort to mitigate GHG emissions in the present. The paper concludes “it is not too late to mitigate climate change and to improve adaptive capacity,” and that “looking at the benefits of climate mitigation in terms of avoided potential displacements may be a useful complement to estimates in terms of economic gains and losses.”

With as much as one-third of our global population expected to experience mean temperatures of 29 Celsius, we cannot afford to wait on tackling the GHG emissions causing global warming. The areas of the planet most affected are already the least capable of adapting to these forecasted changes. Many of the countries located on the edge of uninhabitability today, will certainly be totally uninhabitable in 2070.