August 28, 2016 – The climate change we are observing today is anthropogenic in origin. It is by far the most formidable challenge we humans face in the 21st century and beyond. But to master it we have to address not just the carbon dioxide (CO2), methane and other greenhouse gases our modern industrial society produces. We also must come to grips with the three “Ps” that hold us back from achieving a successful outcome.

You may ask what do population, politics and policy have to do with climate change? The answer is “everything.”

Mastering Population a Critical First Step

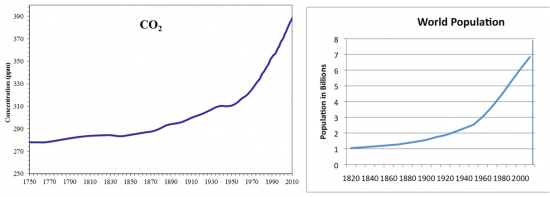

Look at the two charts below.

On the left we trace the rise of CO2 levels in the atmosphere from the mid-1700s to 2010. On the right we trace population growth from 1800 to 2010. The correlation of these two curves is more than coincidence. More humans on the planet directly contributes to more CO2 output from human activity.

We are closing on on 7.5 billion today and United Nations’ estimates by mid-century has our global population reaching upwards of 10 billion. Our current rate of population growth is an additional billion every 13 years. Those who study demographics believe that rate of growth will slow towards 2050. But if it doesn’t the projections will be off by at least a half billion.

Any way you look at those population numbers and the trend in the CO2 chart and you know that without an abrupt change in our behaviour we will see greenhouse gases rise well above current levels.

In a 2009 Earth Talk column appearing in Scientific American, a reader asked the question, “To what extent does human population growth impact global warming, and what can be done about it?”

The response stated that a four-fold increase in human population in the 20th century was accompanied by a twelve-fold increase in CO2 emissions. The conclusion drawn stated “population, global warming and consumption patterns” were linked and that “the overriding challenges facing our global civilization” was to address both the climate and population growth. The Worldwatch Institute has stated, “If we cannot stabilize climate and we cannot stabilize population, there is not an ecosystem on Earth that we can save.”

An illustration of just how serious the population bomb is lies in what is happening in Africa. In a February 2016 article appearing in Scientific American, author Robert Engelman of Worldwatch writes about Africa’s population growth indicating that based on current birth rates we could see the continent exceed 6 billion by 2100. This is three times the total that conventional projections done by the United Nations had forecast.

So why project a number so high? Because African governments for the most part have turned a blind eye to runaway population growth, partly because of cultural norms which value large families, and partly in response to the HIV pandemic which devastated Sub-Saharan African countries for several decades leading to governments encouraging increased birthrates.

Engelman states that “Africa’s situation is already bleak,” and goes on to cite high rates of poverty, malnutrition, overgrazing of domestic animals, low crop yields and conflicts over land and freshwater. He points to some of the wars in Africa as correlated to population growth accompanied by declining resources. Extreme weather events are on the increase in Africa as they are in other areas of the globe. But in Africa with its youth-dominated demographics the despair that comes from the continent’s condition has produced polls that show as many as 37% of young Sub-Saharan Africans want to move away. The boat people crossing from Libya to Italy are evidence of the desperation that many Africans feel about their continent’s future.

For Africa’s leaders, predominantly male, the prospects for their countries and the continent are indeed ominous. For the world community having to deal with an Africa unable to feed itself and with its population seeking a place where basic needs can be fulfilled, represents an external challenge that they may be incapable of providing sufficient assistance. A new African strategy is needed fast. And that’s where politics and policy need a new set of marching orders.