June 21, 2017 – When NASA this week held a news conference to talk about more exoplanet discoveries it was almost a ho-hum affair. Astronomers working with the Kepler Space Telescope over the last four years have found thousands of exoplanets. This latest find of 219 additional planets beyond our Solar System produced 10, deemed habitable. That is, they met the criteria of the “Goldilocks Zone” and their size was comparable to Earth.

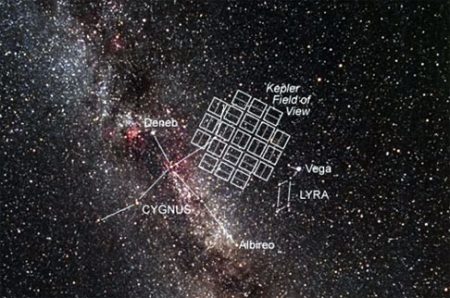

Near-Earth analogs represent only a small percentage of exoplanets discovered so far. Some are deemed “Super Earths,” because they are larger than our planet but smaller than Neptunian-sized worlds. But the reason they are deemed analogs is, they can sustain water in liquid form on the surface. And it appears that only Kepler has been able to make these planets known to us. No other space or ground technology has spotted Earth analogs. The most interesting discovery so far is the sheer volume of these worlds, 50 in an exoplanet inventory of 4,034. That amounts to better than 1.2% observed to date. And when you consider Kepler is only looking at a small subset of the sky near the Cygnus constellation, it infers that there are many more Earth analogs to be discovered.

States Benjamin Fulton, University of Hawaii at Manoa, a lead author of this latest study of Kepler discoveries, “we like to think of this study as classifying planets in the same way that biologists identify new species of animals…….finding two distinct groups of exoplanets is like discovering mammals and lizards make up distinct branches of a family tree.”

To what is he referring in describing two distinct types of exoplanets?

As Kepler has searched it has found Jovian-sized gas giants and smaller rocky planets. The gas giants were the first to be found because their size made the detection easier.

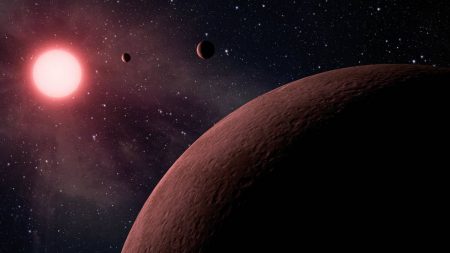

The second category of rocky planets has implications for life in the Universe beyond Earth. Half of this latter category even though existing within the “Goldilocks Zone.” appear hostile to life being Venus-like with a thick atmosphere and a runaway greenhouse effect.

The remaining half, from planets the size of Mars then Earth, and finally to “Super Earths” approaching the size of Neptune, appear more amenable to biology. What has been interesting so far in the Kepler data is the proliferation of rocky planets 75% greater in mass than Earth. Astronomers can’t explain the prevalence of these large Earths but note that gravity on the surfaces of these planets would impact biology in very different ways than what we see here on our home world.

Kepler continues its mission looking at new patches of sky and should produce future NASA news conferences giving us a glimpse of a galaxy and Universe we may physically never reach. Our physical roaming to the stars may be confined to our home Solar System considering the enormous distances between systems. But our ability to see the details further out has proven fascinating.