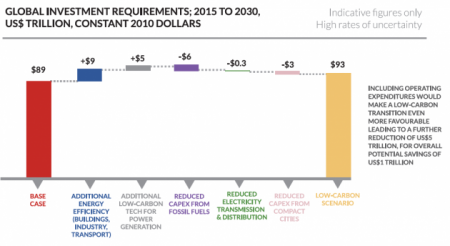

April 19, 2015 – The World Bank, International Monetary Fund and United Nations held a powwow in the last week along with representatives from 42 countries. Collectively they concluded that the next decade-and-a-half will require a global investment of $89 trillion U.S. in infrastructure, energy, land use systems and urban development to meet the challenge of climate change. An additional $4 trillion would fuel the permanent transition to a low-carbon economic future keeping temperatures within the internationally agreed to target limit of no more than a 2 Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) rise.

By making this global investment the world would gain the benefit of operating in a new paradigm, a low-carbon infrastructure costing far less than our current fossil-fuel energy paradigm. In the end there would be winners and losers. Holding back the seas for countries threatened today would not be possible. Relocation of citizens would be the only answer. And the other losers, the fossil fuel companies, would find themselves stuck with significant stranded assets. For them “business as usual” would no longer be possible.

The one thing those attending the joint meeting agreed upon was a low-carbon transition would only be financially viable if a price were put on carbon globally and if fossil fuel subsidies were ended. The money saved frome one and the revenue raised from the other would be sufficient to help those immediate victims of climate change adapt to changing circumstances. It certainly wouldn’t be sufficient to meet the larger investment target of $89 trillion. But it would be a good start.

For our planet “an ordered transition to a well-functioning, low-carbon economy” will require investments in improving the energy efficiency of existing infrastructure everywhere. It will require a significant investment in renewable energy, in nuclear and also in carbon capture and storage (CCS) where the latter would offset our need to continue to use coal and natural gas in this century. By 2100 that need would end with the full low carbon transition complete.

Our method of energy distribution would change not only in the way we produce it but where and how it is delivered and consumed. A good amount of the trillions we spend would go into urban investment to produce more compact and connected cities with better mass transit, reduced congestion and far less pollution.

But right now our current business models, accounting and investment rules are not designed to encourage the kind of investment we are talking about. Investment today is all about the short-term. Take for example the way my portfolio is built. I have mutual funds managed by a financial adviser who constantly does short-term reviews and adjustments to my assets. The holding period, therefore, for one or a group of stocks is watched and measured against a series of parameters. Not necessarily liquid but certainly not illiquid these investments are not the kind that are designed to benefit future generations. And they seldom are focused on infrastructure.

So the first thing that needs to be done is creating new ways to entice the financial industry into longer-term, illiquid, low-carbon investments that take into consideration social and environmental risks. Banks need to become early-stage risk takers on emerging technologies that are oriented to getting us greener. Capital pools need to be established for municipal governments to fund individual clean energy, urban intensification and energy efficiency building projects. In addition we need to see a significant expansion of high-yield green and infrastructure bonds to create sufficient capital for large-scale projects like mass transit.

And as for the funding of low-carbon initiatives in the Developing World, loans from richer nations should be denominated in the local currency to minimize the potential for default should the currency’s value fall against that of the loan provider.

And since cities will be where 70% of us will live by mid-century it would seem that reform of municipal financial structures is imperative.

For example, I wrote recently about Miami Beach funding its climate mitigation projects by issuing new building permits to condominium developers on the beach. The reason, the city only has property taxes and development fees from which to get revenue. This type of restrictive revenue model makes no sense in an urban world. Cities need to have the authority and financial resources to make the critical investments that align with the goals of a low-carbon end result.

Another example, in Toronto, where I live, traffic congestion and pollution combined with an antiquated and inadequate mass transit system has produced gridlock. But the city largely raises revenue from rate payers and their property taxes. So for projects that go beyond the daily operation of the city and all its services it goes cap in hand to provincial and federal levels of government in its search for capital needed to fund projects to end the congestion. It has limited taxing authority and thus other than a levee on homeowners must find creative means to fund infrastructure.

The same holds true for investment in energy infrastructure. The models of the past, large utilities and massively integrated power grids, must undergo a dramatic change. A low-carbon energy future includes small-scale power generation using renewables, modular nuclear, smart grids, micro grids, and off grid energy production and distribution. The costs to continue to operate current carbon-based energy production technology can only continue with incremental investment in CCS. If not then the carbon-based energy source must be shut down to be replaced through more investment in the aforementioned new sources. Green climate funds dedicated to energy production and distribution will be essential over the next decade-and-a-half to capitalize the transition.

It is true that in this mix of new financial policy the problem of stranded holdings will at some point require a write-down in the book value of companies today deemed to be energy giants whether fossil fuel producers or operators of coal-fired power plants. For Exxon-Mobil, BP, Royal Dutch Shell, and coal mining companies, no longer able extract fossil fuels from asset holdings will mean hundreds of billions in potential investor losses. Ultimately once assets are declared stranded the hit investors will take will be a one-time thing but its impact cannot be underestimated. The recourse for a world instituting a low-carbon outcome is to match the loss investors take from the stranding of assets with opportunities to invest in the new high-yielding financial instruments of the low-carbon transition.

None of this will be easy, but all is necessary. $89 trillion is a daunting number. Over 15 years it amounts to a little less than $6 trillion a year which equates to $16 billion per day. The sooner we get started the smaller the total bill and the closer we will be to minimizing global warming’s impact. Any delay will add trillions of dollars to the cost.

And according to those at the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and United Nations member countries, “the good news is that between public and private sources there is sufficient capital available globally to finance an energy transition.”