September 16, 2016 – In Canada accounting for carbon today is complex because there is no single authority establishing a pricing or industry cap on emissions. Instead the provinces under Canada’s constitution have primary responsibility for what gets emitted into the air. It does seem somewhat strange to those readers who are not Canadian that our atmosphere which knows no borders is governed by sub-jurisdictions. But that is the nature of Canadian federalism.

This presents a problem for our federal government in implementing a national carbon strategy based on commitments made at COP 21. In an article appearing in today’s Globe and Mail Report on Business, Tracy Snoddon, author of a C. D. Howe Institute study on this subject declares that to-date all the “heavy lifting” related to carbon has been done by provinces with themes and variations across the nation. British Columbia has been sitting on a $30 per ton carbon price for a number of years. Quebec and Ontario through cap-and-trade have priced carbon at $16 per ton to start. Meanwhile the federal government has promised to institute a national carbon price starting this fall. Will it be $16 or $30 or somewhere in between? Whatever the decision may be, establishing a uniform baseline price on carbon is an essential step for a country to begin accounting for the carbon it emits.

Canada will soon be joining other nations committed to the COP 21 agreement at the next world gathering. COP 22 will begin operating the terms of the Paris Agreement. Article 6 of that Agreement establishes a global carbon market with every nation made responsible for determining its contribution to emission reductions. These nationally determined contributions or NDCs will vary as much as the carbon policies found in different Canadian provinces.

Article 13 of the Agreement introduces an inventory framework for reporting emissions by source and removal by sinks using common methodologies from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). What makes all of this even more complicated is the interactions among countries where high emitters buy credits from low emitters to offset their emission contributions.

So how does this work?

Let’s use Canada as the example. The country has set a target not to exceed 5,650 Megatons of greenhouse gas emissions released to the atmosphere between 2020 and 2030 so that it can meet reductions of 30% below 2005 levels by the latter date. What happens if the country exceeds that ceiling?

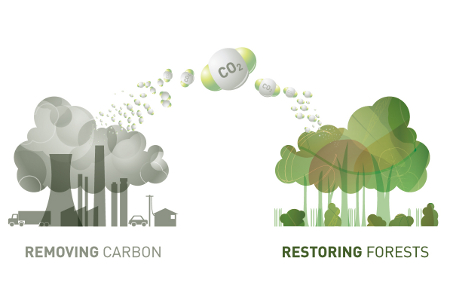

A solution is to purchase carbon credits from another country that is producing emissions below its established targets. The credits could be purchased from a Developing World country that is expanding expanding forests to create natural carbon sinks.

In the example if Canada doesn’t keep emissions below 5,650 Megatons, then the excess greenhouse gas emissions must be accounted for. Let’s say the total is 5,700 Megatons. Canada purchases credits equal to 50 million tons based on the unit price set for carbon.

Would that price be globally determined or be negotiated between the buyer of carbon credits and the seller?

If $30 per ton Canada would pay $1.5 billion. But if a world price on carbon is agreed to by signatories to COP 21 as the agreement is enforced that is much higher then the cost would go up?

How likely is a ton of carbon in 2030 to be priced at $30? Highly unlikely according to Tim Wiwchar, project director for the development of Shell Canada’s Quest carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) plant in Northern Alberta. In the last week Quest achieved a milestone, a million tons of carbon extracted from production processes and stored permanently underground. According to Wiwchar, CCS as a carbon reducing strategy really becomes economically self-sustaining when carbon is priced at $100 per ton.

Quest cost $1.35 billion to build. The majority of the money spent came from the governments of Alberta and Canada. As part of the agreement the plans for the plant’s construction and operation were made publicly accessible so others can use them to build CCS projects of similar scale. Wiwchar believes that future CCS projects can cost 20 to 30% less to construct and operate than Quest. He also believes there are enough production facilities and underground storage capacity to add 20 more projects equivalent to it in Western Canada alone. Around the globe the potential for CCS projects is far greater numbering in the tens of thousands. But the accounting must add up. And Wiwchar believes the right accounting number is $100 or higher per ton.