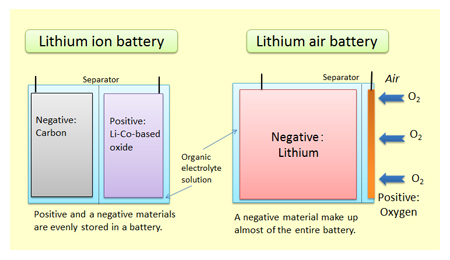

January 28, 2015 – The promise of electric vehicles (EVs) is very much dependent on improvements to battery technology. Today’s lithium-ion batteries consist of a series of cells that contain layers of lithium separated by cobalt-oxides. Lithium salt is the anode. Lithium cobalt oxide is the cathode. Ions travel between the two to create an electric charge. But if you could remove the oxidizer from the battery and substitute air (see diagram below) then you reduce the battery weight and size, and extend the life of the charge.

A commercial lithium-powered battery has been the goal of a number of universities and commercial laboratories with varying success and a lot of failures. The latest progress comes from Yale University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The failures have largely been because lithium when exposed to air gets chemically altered and loses its ability to be recharged. Coming up with the right materials to act as a filter then is critical to improving the batteries overall efficiency as well as extending its recharge cycles.

To achieve this the Yale and MIT teams are experimenting with nanotechnology, creating nanostructured membranes made from catalyst-coated polymer nanofibers. The results so far have been a doubling in the number of recharge cycles to 60 in the lab. But only in the lab because the current test battery requires pure oxygen, highly impractical in the real world.

For lithium-air researchers the ultimate goal is to build a battery that operates in normal air while equaling the 1,000 recharge cycles capable in current EV batteries. The move from pure oxygen to air is not trivial. The presence of carbon dioxide in normal air alters the chemistry of the battery creating lithium carbonates which inhibit recharge cycles. So the batteries die pretty quickly.

But there is no doubt that a lithium-air battery, and other experimental air-based batteries using zinc and aluminum would prove to be disruptive for the entire transportation technology industry segment. These batteries would weigh a fraction of what is currently found in EVs and would require much smaller form factors. This would mean engineers would not be constrained by the battery in designing EVs from small to large to meet every transportation requirement including building commercial aircraft powered by electricity. It would also mean extended range equal to most gasoline and diesel-powered vehicles on the road today making the move to low-carbon transportation solutions viable.