I have been writing about artificial intelligence (AI) a great deal in the past few because of the emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT. In addition, I have received many submissions from authors who want to contribute to the conversation. As a result, I am putting together this conversation series on AI to share with 21st Century Tech Blog readers.

What follows comes from the pen of Professor Ioannis Pitas who is the Director of the Artificial Intelligence and Information Analysis lab at Aristotle University in Thessaloniki, Greece. He believes a large number of academics, scientists and business people are demonstrating technophobia in response to the emergence of LLMs.

Professor Pitas’ is also the Board Chair of AIDA, the AI Doctoral Academy, a global portal where you can find the latest AI research. He believes the current work on AI should continue, but what is needed is for all of us including the laypeople, academics, scientists, and those in business to become better educated so we can embrace what this technological advance brings to the collective table for all humanity.

I have taken the substance of Professor Pitas’ submission to present to you and welcome your comments. Remember, this is the first part in the AI conversation. So more will follow.

Overcoming AI Technophobia

Currently, there is a public surge of interest in AI topics, especially in Large Language Models, like ChatGPT. This is not a random development.

AI is here to stay and will have huge social and economic implications, seen as both a blessing and a curse. In view of its potential dangers, many AI scientists have expressed concern over AI developments that border on technophobia. But there is a means of defending ourselves from the dark side of AI as expressed in dystopian science fiction.

What can be done? One approach which many are advocating is to apply guardrails and regulations to AI development, something that the publisher of this blog site has written about and advocated. But I believe a better approach would be to educate the public about AI to know the risk and benefits.

Citizen Morphosis

AI is a technology that has arisen out of humanity’s response to an increasingly complex, globally interconnected world, and to the crises in our natural and human-engineered environments. The growth process of physical and social complexity is deep and seemingly unstoppable.

Today, data increases exponentially while knowledge grows linearly. This has to change. The need to make knowledge grow exponentially through educating the public is what I call “citizen morphosis,” citizen formation, a Greek term that emphasizes the need to equip all of us with critical thinking, precise multimodal communication skills, imagination, and emotional intelligence. This morphosis will give us the means to understand, adapt, and ultimately harness the tremendous technological and economic possibilities that lie ahead in the 21st century.

Our need to change how we are educated permeates all levels of society. It is simply not sustainable that one-third of humanity understands and benefits from scientific progress, while the remaining two-thirds are impoverished and technophobic. All should reap the benefits of knowledge including the people of the Global South and North, or we may eventually face a catastrophic social implosion similar to what happened with the demise of Rome and the dawning of the Middle Ages in Europe.

Fortunately, the basic concepts necessary for understanding AI and Information Sciences (e.g., data similarity, clustering, classification) are simple and can be taught at all educational levels. If properly taught, these concepts can easily be grasped.

But to change education requires political will and follow through from primary grades to secondary and post-secondary, and then through ongoing learning after joining the working world.

Today, many countries have adopted STEM curricula. STEM stands for the teaching of science, technology, engineering and mathematics. But mathematics needs to go beyond sciences and engineering and into the humanities. Mathematics has a place in the social sciences. And so does another subject, informatics.

The term informatics is usually associated with computer science, but in this case, informatics embraces far more than bits and bytes, code, and circuit boards. That’s why I propose the creation of Schools of Information Science that feature departments that cover informatics, mathematics, computer Engineering, AI science and engineering, and Internet/Web science.

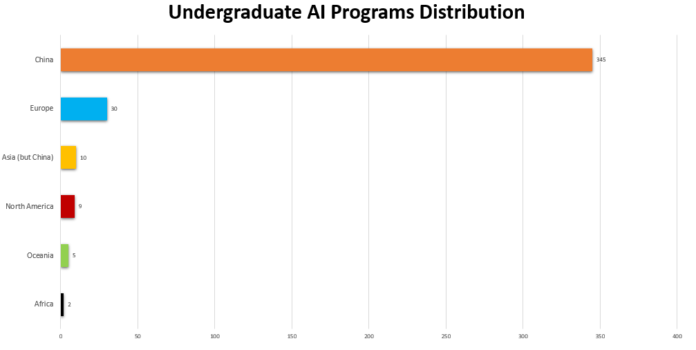

In China, as you can see by the graph at the top of this article, there are already post-secondary undergraduate programs embracing AI in far greater quantity than anywhere else on the planet.

But what I propose goes beyond teaching AI courses. There needs to be a fundamental shift to information and knowledge in an independent subject called Information Science and Engineering to be treated on an equal level as learning the hard sciences like physics and chemistry. We have to expand the past association of the word informatics beyond computer science to encompass for example AI and Network/Web science and engineering. This new Information Science and Engineering curricula will be the mother science of all other information-related disciplines.

If you question this fundamental principle, let me remind you that in the 19th century, the move away from classical education and the physical sciences to engineering gave birth to our modern world.

Humanities Should Mine the Mind

I further propose a creation within humanities curricula of courses that mathematize the social sciences. Currently, the humanities face the greatest pressure from AI advances (ChatGPT can write an essay, a book report, a test, and more, and get pretty good grades). Indeed, the mathematization of classical subjects such as linguistics, psychology, and sociology would lead to new curricula such as philology/linguistic science and engineering, social science and engineering, and more. Being a fan of classical studies, though an engineer by training, I believe there is merit in retaining non-STEM studies, but with a twist.

The health sciences need to be rethought to incorporate advances in bioscience and engineering with new curricula covering subjects like genetic engineering and systems biology.

And there should be mandatory courses on mathematics and computer science in all the sciences. Simply, one or two courses in statistics or programming do not meet current needs.

Given the inertia of the global educational system, I am not naive to believe that such ideas can be implemented without pushback or overnight. But I am hoping that in starting this conversation it will reach the eyes of political leaders, academicians in universtieis and colleges, and those in the business world globally so that we can generate a society where knowledge growth keeps up with technological advances to embrace what is best in them to help humanity progress in the 21st century and beyond.