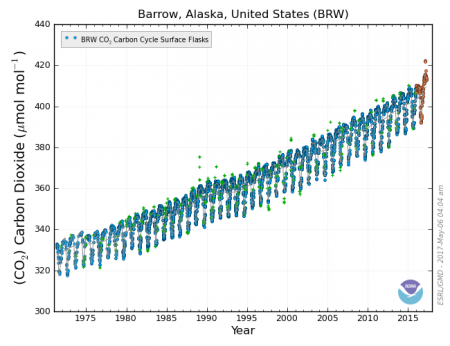

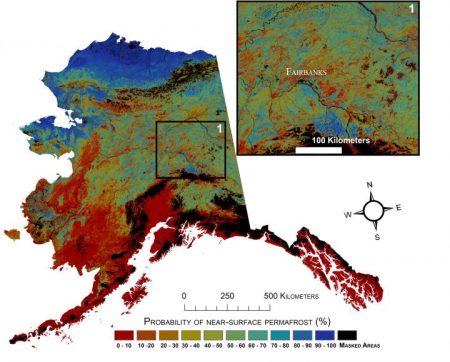

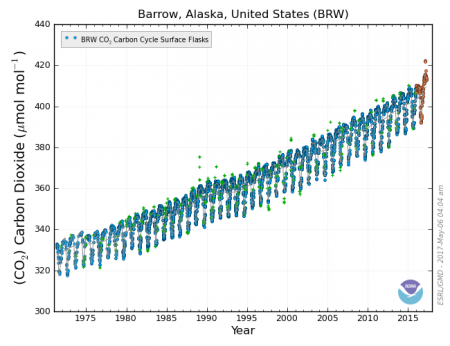

May 14, 2017 – A new study by Harvard University, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and other affiliates shows that permafrost in the face of global warming is no longer a carbon sink, but rather, a net emitter. In the researchers’ paper entitled, “Carbon dioxide sources from Alaska driven by increasing early winter respiration from Arctic tundra,” it states that “tundra ecosystems” are now a net source of CO2 emission. What has always been feared by climate scientists is now confirmed by data collection. At Barrow station in Alaska, CO2 emissions from surrounding tundra have increased since 1975 by 73%.

Normally, as Arctic winter approaches, the permafrost becomes a net carbon sink. But as summer temperatures in Alaska have risen the ability of the permafrost to function as a sink has lessened. The authors of the study believe that current climate models are underestimating the impact of Arctic greenhouse gas emissions as the region warms at twice the rate of the global average.

The natural planetary cycle is fairly well understood. In the spring when plants germinate they become natural carbon sinks. In the fall when the plants die they become net emitters as they decompose. That pattern is consistent with observations made at the Mauna Loa observatory that tracks atmospheric CO2. It’s as if the planet inhales and exhales annually with the inhalation stronger in the Northern than in the Southern Hemisphere because of disproportionate land mass favouring the former.

The Barrow station study compiled data from NASA aerial missions over a 3-year period (2012-14) plus 41 years of CO2 measurement from NOAA sensors on location, supplemented with satellite remote sensing data. The researchers were able to separate permafrost CO2 emissions from fossil fuel, wildfire, and miscellaneous human sources.

Lead author, Roisin Commane, Havard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, points out that Alaska’s ground isn’t freezing up in October and November the way it used to in the 1970s. “In some places in Alaska, it’s taking nearly 100 days until the entire layer, about 1 meter down, gets frozen hard through.”

The research paper was published coincident with the 10th meeting of the Arctic Council hosted by the United States in Fairbanks, Alaska in the last week. The nations of the Council, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States, in their concluding documents reiterated a commitment on “actions to mitigate and adapt to climate change.” That conclusion runs counter to the current policy drift in the United States driven by recent climate change skeptic appointments to key positions in the Trump administration.

The Barrow station study is not a standalone. Recently independent research done in the Canadian North indicated that as much as 1.3 million square kilometers (a half million square miles) of Canada’s Arctic is experiencing similar increases in CO2 and methane (CH4) emissions. You can read more about this study in a posting written on this blog site back on March 5th, 2017.

Swedish scientists have seen similar results. And evidence in Russia points to significant CO2 and CH4 eruptions from melting permafrost that has produced massive sinkholes.

As the 15 million square kilometers (5.8 million square miles) of permafrost loses its capacity as a carbon sink, it means the biomass contained within it will release an entire range of chemistry and biology to northern rivers and lakes that have been trapped within it since the last Ice Age. That represents more than a greenhouse gas emissions problem. It also threatens the health of Arctic animal and plant life, and the humans who live and work in the Arctic.