August 30, 2019 – This week in my science reading uncovered two stories I would like to share with readers.

Oxygen Overshoot Causes Massive Life Die-Off

The first research article focuses on the collapse of life on Earth after the Great Oxidation Event (GOE), a dramatic growth of atmospheric oxygen some 2.5 billion years ago that was followed by an extinction event. Described as an “oxygen overshoot” Earth’s microbial plant life flourished producing copious levels of oxygen. Paleobiologists describe the GOE and the following transition as a period of feast and famine that lasted 1 billion years.

How do we know this happened?

The clues are found in multi-billion year-old rocks on an island at the north end of Hudson Bay in Canada’s Arctic. The mineral barite laid down at the time captured the oxygen levels in the atmosphere showing huge changes as a result of the planet’s growing biosphere, followed by a massive drop off of life around 2 billion years.

Why did it happen?

The GOE happened because of the blooming of life in Earth’s early oceans. Ancient microbial plants (think algae) through photosynthesis flooded the atmosphere with oxygen. The growth was spectacular producing lots of free oxygen absorbed into the atmosphere. When food supplies ran out, like an algae bloom that grows and dies, the microbial population collapsed as did the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere.

What does this tell us about the environment of early Earth?

It was far different than today where plants and animals balance each other out keeping oxygen levels in the atmosphere in equilibrium. Early earth was anything but stable for life to establish itself. And it tells us something about our Earth today and the fine balance that keeps our planet in equilibrium.

The recent fires in the Arctic and Amazonia, we are told, could alter the balance of atmospheric gases, as well as cause significant harm to Earth ecosystems dependent on the forests in these areas. It tells us about how positive feedbacks from changes to planetary conditions can produce catastrophic outcomes.

In the ancient atmosphere, the successful expansion of microbial plant life created a super oxygenation event which reinforced life’s growth beyond the carrying capacity of the planet’s environment at that time. In the end it led to a series of extinction events. In our modern discussions about climate change, we refer to such events as tipping points.

Life Under 50,000-Year-Old Permafrost Blows Researchers Away

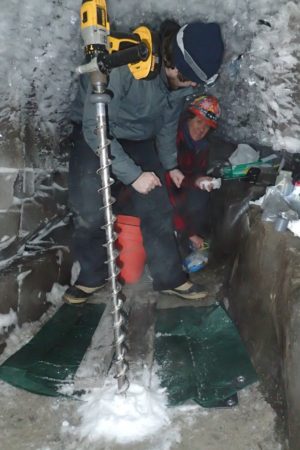

The second story that caught my eye was about a earlier in the year announced discovery in Alaska where researchers drilling into the permafrost found a trapped briny water deposit called a cryopeg. The scientists estimated the water had been preserved under a permafrost cap for 50,000 years.

This wasn’t ordinary water. In its isolated environment, it was filled with concentrated salt (14% by weight) and ti was very cold. Water this salty, if used to preserve canned foods would be sufficient to kill any bacteria on the surface of the planet today. So could anything survive in this ancient pocket of saltwater?

What did the research teams discover?

Described as a robust community of microbes and viruses, the scientists were startled by not only the existence of, but also the density of this living community. In fact, the amount of life found in the cryopeg appeared to be in concentrations much greater than would we bound under sea ice today anywhere on our planet.

What are the implications of this discovery?

For exobiologists studying ice deposits on Mars, and the planets and moons from the Outer Solar System, the discovery strongly suggests, that life once established, has an ability to flourish even in the most extreme and exotic environments.

The implications for life on Mars which was once home to a surface ocean and today contains subsurface ice deposits, could be enormous. Or for life on Europa, Jupiter’s sixth-closest moon, characterized by a thick icy crust concealing a saltwater ocean with water volumer larger than all the oceans on Earth. Or for Saturn’s moons, Enceladus and Titan, both with saltwater oceans of their own lying beneath the surface. Or for Triton, Neptune’s largest moon, which could also harbour life in its watery depths. And finally, for Pluto, the dwarf planet of the Kuiper Belt that also, as we have recently learned, is geologically active, and is suspected of having its own subsurface ocean.

If life can be found deep under the surface of Earth where none was anticipated, and if that life can survive for tens of thousands to millions of years without access to the surface, then conceivably life can exist in these other extreme environments. That once life establishes itself for even a short period of time it can become robust enough to survive changes to its environment that we would consider extreme, and yet thrive.

That is one of the reasons for concerns about NASA’s ambitions to land human explorers on Mars in the 2030s, or Elon Musk’s call to establish a human settlement on the Red Planet by the mid-century. If we are to go to Mars carrying our own microbiome, we may permanently alter the native life of Mars as we probe into its ancient subsurface ice formations in pursuit of resources we will need to survive there: hydrogen, oxygen, and water.

And NASA has also announced a Europa mission in the works to first survey the moon from orbit, and possibly even deploy a lander to look for what lies beneath its icy surface. The fear is we are as likely to plant life there from Earth as we are to find Europan native life. To me, that is a disturbing consequence of our current scientific and human space mission planning.