February 2, 2020 – I know no groundhog saw its shadow here in Toronto today. Both Punxsutawney Phil and Canada’s Wiarton Willy also saw no shadow which means, an early spring…..or not.

Thinking that a groundhog could possibly possess the skills and knowledge to predict the weather when our homo sapien weather gurus struggle to get it right, got me thinking about intelligent species in the animal kingdom.

That made me think about the “lowly octopus, squid, and cuttlefish.” These three species are classified as cephalopods and are as alien to vertebrates as almost any other creature on the planet. their brains are equated to be as smart as dogs, if not smarter, and defy all our conceived notions of what makes animal species smart.

Even odder is seeing the high levels of intelligence these animals exhibit while only living very short lives compared to intelligent vertebrates. Cephalopods have lifespans that vary from 6 months to 5 years. In vertebrates, we associate long lifespan with intelligence and point to elephants, whales, parrots, crows and humans, who all exhibit high intelligence. But in the octopus, squid and cuttlefish, you have an animal that shows cognitive skills equal to if not greater than most of the vertebrates on the above list while living very shortened lives.

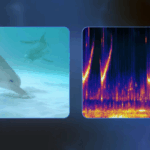

Cephalopods are fascinating to watch. They employ deception in seeking food. They can hide food from other cephalopods using misdirection. They change appearances in an instant. Some use bioluminescence to freeze prey. Their tentacles are equivalent to an elephant’s trunk, or a human hand but even better, containing 10,000 neurons and sensors that touch, taste and smell. And their main brain demonstrates sentience on another level entirely.

When you first encounter an octopus, it is hard to not notice their eyes. They are as sophisticated as those found in vertebrates and in their 600 million years of evolution have developed camera eyes similar to ours but with additional ways of processing visual information, we cannot even fathom. They always are watching and they respond to humans in the wild or in a fish tank in ways that suggest they are our equals.

An invertebrate that exhibits the kind of mental complexity and behaviours states Peter Godfrey-Smith in an article that appeared in Scientific American in 2017, states, “they are probably the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien.”

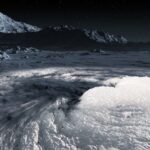

Godfrey-Smith notes their evolutionary roots go back 600 million years to the beginning of the Cambrian explosion when complex life first started appearing in the oceans and well before the first invertebrates and vertebrates appeared on land. And in terms of their intelligence, it may have developed smarts well before any of our chordate ancestors, an intelligence that is very different from vertebrates, and that reflects their anatomical structure.

So just how smart are cephalopods? We have yet to meet an octopus Einstein but we certainly have witnessed amazing behaviours.

In captivity, octopi have been observed doing food raids outside their home tanks, slipping out or through pipes and emerging in another aquarium to grab a snack. At the University of Otago in New Zealand, octopi have learned to turn off lights in a room by squirting jets of water at the wall panels to cause them to short out. The university described it as such a nuisance that the researchers released the animals back into the wild.

Octopus and squid can recognize different people outside their tanks even to the point of distinguishing them when wearing identical uniforms. They are situationally aware unlike fish in an aquarium. A captive octopus knows exactly where it is and will mess with its human keepers if so inclined by trashing the tank’s life support equipment causing floods. It could be they are plotting an avenue of escape.

And then there is the observed behaviour of octopus turning non-food objects into toys, a curiosity seen in higher intelligence vertebrates.

Other than the tentacles and the lack of bones, how different are cephalopods. Our nervous systems and spinal cord derive from our fish, reptile, bird and mammal ancestors. The octopus, squid and cuttlefish evolved from flatworms with neurons distributed in bunches throughout the body and interconnected running through the body. Over the 600 million years the bunches turned into the neurons that populate the tentacles, twice as many as can be found in the central brain. Some researchers believe the neurons in the tentacles have their own memory while the central brain controls overall motion. It is akin to a combination of top-down and localized control.

A final note. My wife and I are heading to Costa Rica for the next two weeks. I’m bringing my chromebook along for the ride and may from time to time write something new. And while we are in Costa Rica I will recharge my batteries so that when I’m back I can continue to share my curiosity about science and technology with all of my many readers.