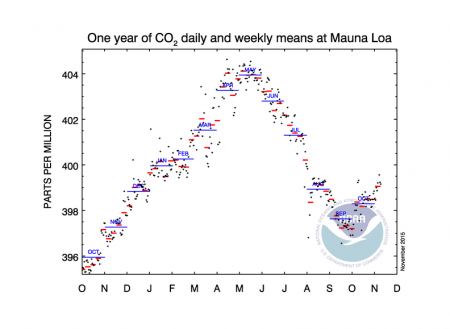

November 9, 2015 – Just exactly how much CO2 is in the atmosphere? Back in May 2013 I reported that the observatory atop Mauna Loa in Hawaii had recorded CO2 concentrations exceeding 400 parts per million for the first time. But in the last week scientists reported that 2016 would be the year we surpassed 400 PPM. So what gives? Well it seems the Manua Loa record in 2013 was obtained at CO2’s annual peak. You see CO2 levels vary in the atmosphere throughout the year. When the northern Hemisphere is in summer CO2 levels decline because trees and vegetation are natural carbon sinks and most of the continental land mass lies north of the equator. But when winter approaches CO2 gets released by dormant and dying vegetation and levels creep upward until they hit a peak before the start of the next summer. It’s like the atmosphere is breathing in and out. Inhaling in the summer and exhaling in the winter.

So that explains why the May 2013 400 ppm level was only temporary and seasonal. This May the annual oscillation in CO2 levels exceeded 404 ppm. But on November 1, 2015, CO2 levels had dropped to 399.06 ppm. Now compare those numbers with the same date in 2014 when CO2 levels were at 397.7 ppm. A year before that the level was 396.78 ppm. A decade ago it was 377.72 ppm. And for final comparison go back to 1750, before the Industrial Revolution got started, and look at CO2 levels from air trapped in ice cores taken from mountain and polar glaciers. The reading then was 278 ppm. We’ve gone up 122 ppm, an increase in CO2 concentrations of 42%.

In the run up to COP21 in Paris where the nations of the world are hammering out a climate change agreement the hope is to limit further increases in CO2 to not exceed 450 ppm by mid-century. That’s an increase from 1750 levels of 62%, and 12.5% greater than current CO2 levels . At the 450 mark governments hope to keep global mean temperatures from rising no more than 2 Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit). Scientists are quick to remind us that above 350 ppm we trigger global warming with 400 ppm already heading us into “uncharted waters.”

In the run up to COP21 in Paris where the nations of the world are hammering out a climate change agreement the hope is to limit further increases in CO2 to not exceed 450 ppm by mid-century. That’s an increase from 1750 levels of 62%, and 12.5% greater than current CO2 levels . At the 450 mark governments hope to keep global mean temperatures from rising no more than 2 Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit). Scientists are quick to remind us that above 350 ppm we trigger global warming with 400 ppm already heading us into “uncharted waters.”

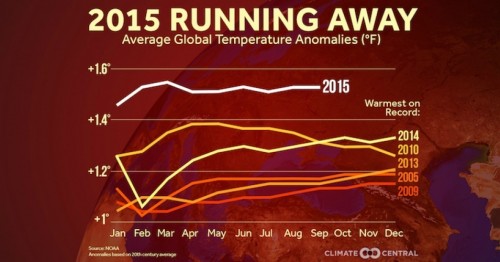

The second bit of science news “coincidentally” reported in the last week is that 2015 will be the hottest year on record for planet Earth if the remaining two months continue the trend of the first 10. According to climate scientists temperatures this year are beating past records “by a country mile” with 1 Celsius (1.8 Fahrenheit) the milestone being surpassed.

Now if you live in Eastern North America you may think this is nuts. After all didn’t we pass through a second frigid winter in a row? And this summer’s heat seemed unexceptional. So how can the scientists state this as the hottest year ever recorded? That’s because world mean temperatures are not governed solely by what happens in a single part of the world. The numbers being crunched are collected from all around the globe. In addition they reflect daytime highs and evening lows. And it is the lows that provide the biggest indicator of rising temperatures. We aren’t experiencing lows that are that low anymore. And so recorded temperatures are creeping up at rates previously unforeseen.

Then there are oscillations that we have witnessed for several decades. One of those is the mid-Pacific El Nino which this year is a further contributing factor to an exceptionally warm 2015. The impact on North and South America has been enormous and yet the El Nion has yet to peak which usually occurs just before Christmas.

Europe and Asia have not been spared the warmth. Having come back from a vacation in Central Europe, where my wife and I were witnesses to climate change first hand, we saw countries experiencing unprecedented warmth both day and night, evidence of extensive drought conditions with crops dead in the field, and a Danube River with water levels so low that our on the water cruise turned into a bus tour.

In India and Pakistan 2015 has proven unkind as well. Record heat in both day and night was described by the Indian weather services this summer, the 5th deadliest heatwave ever recorded. 2,300 died in India from the heat. In neighbouring Pakistan more than 1,000 deaths were recorded with scientists there describing it as the worst heatwave in three decades. Imagine daytime temperatures of 49 Celsius (120 Fahrenheit) in Karachi with nighttime temperatures dropping into the mid-30s (plus 90 Fahrenheit). Karachi is a city with little in the way of air conditioning.

Yes as our leaders convene in Paris we are heading into uncharted waters. And it is what we don’t know about future greenhouse gas concentrations that requires our focus because it is the one thing we humans can control if we make the effort and sacrifice.