When I read that the fossil fuel industry since 1960 has manufactured 9 billion tons of plastic of which 80% is currently clogging landfills, lakes, rivers and oceans, it was quite the revelation.

Despite best efforts and programs to recycle, our cities and governments cannot deal with the accumulating plastic waste of which a mere 9% gets reused while 12% gets burned in incinerators.

A quick survey of my home shows me that I like many are addicted to the convenience of plastic containers, bags, wraps and more. It keeps our food fresh. It doesn’t break like glass. It is woven into the clothes we wear. It is everywhere.

I remember walking on Florida beaches with my dog before the COVID pandemic and counting the plastic pollution I could see from discarded water bottles, plastic fishing lines, and variable-sized half-disintegrated bits of the stuff. This is the plastic I could see. The nanoplastic, microscopic in size, was invisible. These nanoplastics were being ingested by fish, dolphins, whales, sea turtles, birds and eventually us. The stuff could be found in internal organs and the bloodstream.

We have paid a huge environmental price for the convenience of plastic and now under the guise of the United Nations are trying to reckon with the stuff to make amends for the growing environmental nightmare of plastic pollution, just another symptom of our modern human impact on the planet.

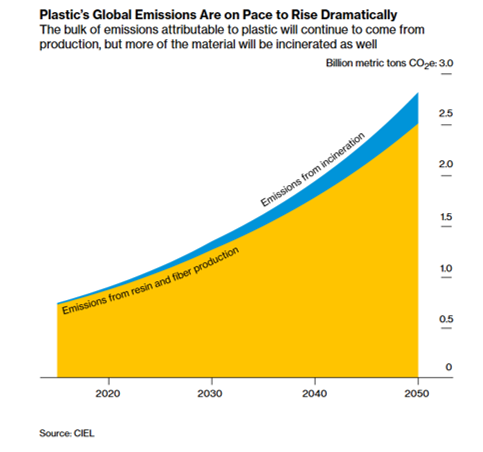

Today, the plastic lifecycle from production to distribution and disposal produces 3.4% or 1.8 gigatons of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions annually. Since plastic is made from fossil fuels, namely oil and gas, it is just a segment of the total contribution that industry makes to rising global temperatures. Left unattended and unregulated, fossil fuel producers will continue to churn out the stuff because they know the insatiable demands of our modern world have made plastic indispensable.

When the United Nations first convened a conference to look at global plastic pollution in 2022, the goal was to put a treaty in place by the end of this year. Annual conferences have been held with the last ending a mere week ago in Busan, Korea.

The conference is entitled the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee or INC. The latest just finished on December 1st and was called INC-5. Like all previous annual events aimed at curbing plastic pollution, no consensus was achieved among those in attendance.

The INC meetings are doomed because they require unanimous agreement among the nations in attendance. That means a single nation can use its veto. That’s exactly what oil and gas-producing nations have done to make it impossible to create a legally binding treaty that puts a cap on plastic production. When the votes were counted, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iran wouldn’t agree to any legally binding international treaty to address plastic pollution that included production caps.

The draft text that didn’t pass, however, is worth summing up. It calls for all parties to the agreement to take appropriate measures to prohibit or reduce the manufacture of plastic products deemed to be hazardous when entering the environment and to pose a risk to human health. It further states that the chemicals used to make plastic be identified with known risks to human health documented. It defines as banned any plastics that cannot be reused, recycled, or composted. It specifically marks microplastics as a danger. It doesn’t prohibit the development of new plastic products but calls for the creation of performance, safety, environmental impact, and other relevant standards to mitigate any risk posed by the chemicals and processes used to make them.

The text describes the establishment of a permanent Scientific Technical Economic Social Cultural Review Committee to develop and provide relevant information to assist member countries as they review existing measures and plan and implement new policies and programs to reduce plastic pollution. A yet-to-be-named plastic phaseout date hasn’t been specified for members to agree to based on their varying timetables that fit within their capacities. None of this sounds unpalatable to the vast majority seeking a way to ween us off our plastic addiction.

The fossil fuel industry and countries dependent on revenue from oil and gas, however, have a very different take. Their arguments for continuing to produce plastic are the same as those they rely on when lobbying for oil and gas production and new well exploration. The common theme was that producing plastic wasn’t the problem. Plastic waste and addressing it would solve the environmental issue. Countries like Saudi Arabia, Russia, Kuwait, and Iran advocated that any treaty coming from the INC discussions should solely focus on managing plastic waste rather than manufacturing.

ExxonMobil, an attendee at INC-5 called for investments in advanced recycling technologies. Other fossil fuel company executives and industry lobbyists argued that the benefits of plastic particularly for countries in the Developing World outweighed the risks.

In the end, INC-5 came up with no agreed text, but like the COP meetings on climate, kicked the can down the road. A concession was not to wait a full year but instead, convene INC-5.2 to happen sometime this coming summer when delegates will renew the battle to establish a global cap on plastic production as a necessary step to reduce its environmental risk.

The majority of nations attending INC meetings want the voting rules changed. They no longer support unanimity and want to see majority rule votes. They want curbs put in place on plastic production. They are opposed by fossil fuel-producing countries and the industry that increasingly is turning to plastic as a key revenue stream to counter the push to clean energy. For the fossil fuel industry, it remains all about the money and not about the environment and the safety of humanity.