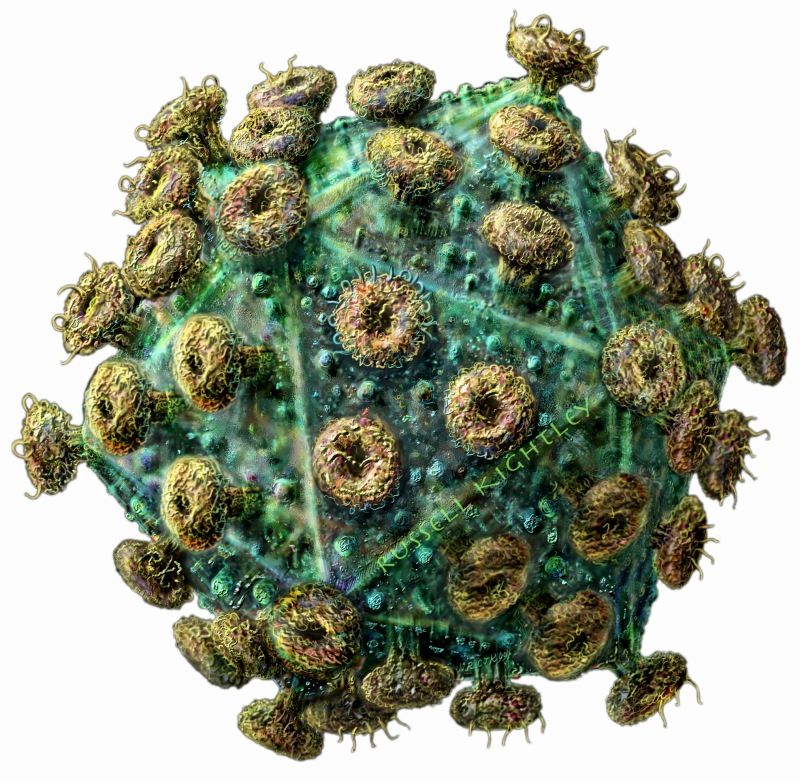

In the last two weeks cures for HIV (the virus depicted in the picture below) have made it into the news. The first documented case of a child born infected with HIV and now “functionally cured” comes from Mississippi where a two-and-a-half-year-old is reportedly free of all signs of the virus. The case was reported at the 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) held this month in Atlanta, Georgia. The attending physician, Hannah Gay, working out of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, described the cure as functional, meaning all standard testing results for the virus came back negative. That doesn’t mean HIV may still be present in the infant, it is just in such low volume that it cannot be screened. Dr. Gay stated, “After at least one year of taking no medicine, this child’s blood remains free of virus even on the most sensitive tests available….this baby has great chances for a long, healthy life. We are certainly hoping that this approach could lead to the same outcome in many other high-risk babies.”

What did Dr. Gay’s team do that was different from other protocols on babies born with HIV? The HIV in the mother was undetected during pregnancy until she was in labour when a routine test came back positive. This put the baby at significant risk so the doctors started administering three antiretroviral drugs 30 hours after the child was born. Typically babies born to HIV=infected mothers have received a course of one retroviral drugs.

After a few days blood drawn from the baby had shown signs of HIV infection and the doctors continued to treat with the cocktail of antiretrovirals. Within a month HIV levels in the blood started falling. Both mother and child continued to be treated but after awhile stopped attending clinics. From age 18 to 23 months the child received no drug therapy and when the mother and child returned to the clinic the doctors fully expected to see higher levels of HIV present. But all the tests came back negative. They even sent samples to labs at Massachusetts Medical School and John Hopkins in Baltimore to corroborate the results. Both these labs had far more sensitive testing equipment. Both found small traces of HIV but no viruses capable of infecting cells and reproducing.

What the medical team concluded was that the child’s cure came about because of the aggressiveness of the treatment after birth. The drugs blocked the HIV virus from infecting short-lived, active immune cells present at birth. The continued treatment also blocked HIV from infecting CD4 white-blood cells. These cells are known to allow HIV to hide in them for years before spreading and becoming AIDS. The doctors believe that the treatment provided would not have worked once CD4 cells were infected. Therefore it is not suitable for older children or adults infected with HIV.

In a second study published on the Ides of March, involving 14 adult patients, the authors of the journal article described their patients as in long-term functional remission seven years after retroviral treatments ended. Again, the key here was aggressive early treatment to control the HIV infection. All patients in this study received treatment within ten weeks after infection. The medication course included a cocktail of antiretroviral drugs administered for a median time of three years. In the study reports the authors state, “Emerging evidence shows that early treatment has long-term benefits. Treatment initiation during primary HIV-1 infection rather than during chronic HIV-1 infection may i) further reduce residual viral replication, ii) limit viral diversity and viral reservoirs, iii) preserve innate immunity and T and B cell functions and iv) accelerate immune restoration.”

The key in both of these case studies for baby and adult is treatment after early detection and before the HIV invades CD4 white blood cells. It will be interesting to follow changes to protocols and treatment plans as physicians adopt similar strategies with HIV-infected patients.