November 16, 2013 – For those who have been reading my blog for sometime you may remember that I have talked about congenital heart disease (CHD) in a rather personal way because my daughter was born with a complex heart lesion that required multiple surgical procedures over the years. She’s 29 now and doing well but her heart disease will remain a major challenge for her throughout her life.

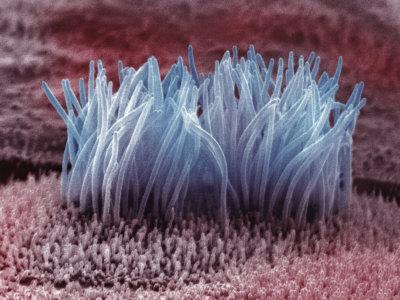

But we are learning far more about the genetic mutations that lead to congenital heart disease and a recent study from Yale University sheds some light on this subject. As reported in the November 13 online edition of Nature, a deletion in the gene Galnt11 is associated with a birth defect that affects the left-right orientation of organs in a developing embryo. It does this because it affects the motility of the cilia, hair-like structures in the body seen in the image below that drive fluid around within the embryo. With the deletion the balance of motile and immotile cilia is altered and this causes improper embryonic development.

Improper orientation of developing organs is the end result. This can lead to a number of CHD conditions including holes developing in the septum of the heart, the wall that separates the left and right pumping chambers. Or reversal of the heart with the weaker pumping chamber pushing blood to the aorta rather than the pulmonary artery.

CHD today is the most common major birth defect with an average of 1 in 100 live births having some form of heart lesion. When first forming the heart begins as a symmetric tube that eventually loops around to form its four chambered array. The role of the cilia in ensuring proper left-right asymmetry has been known for some time. But now because of the Yale study we know of a particular gene mutation that interferes with the process.

Galnt11 joins a group of identified known genetic causes responsible for CHD. And what we are seeing is a preponderance of associated birth defects in 25 to 40% of children who receive a CHD diagnosis. For example 50% of children born with the genetic defect known as Trisomy 21 have a range of heart defects affecting the pumping chambers and septum separating them. Trisomy 13, another genetic defect, is associated with septal defects, as well, in 80% of CHD cases. About one-third of females born with a missing chromosome, known as Monosomy X, suffer from left-side malformations of the heart leading to diseases such as aortic stenosis or hypoplastic left-heart syndrome. About half of males born with Klinefelter syndrome, a condition where the child is born with 47 instead of the normal 46 chromosomes, suffer from patent ductus arteriosus, a condition where the pre-birth circulatory ducts do not close in the normal fashion leading to pulmonary hypertension, and ASD, a condition where holes appear in the septum that separates the upper two heart chambers. The latter condition if untreated eventually increases blood pressure in the lungs leading to hypertension as well.

Where are discoveries like Galnt11 taking us? In finding genetic origins to diseases we are beginning to unlock the mechanism of DNA. This is giving us insight into new methods of treatment and intervention. The emerging field of pharmacogenetics is leading to the development of targeted treatments that can insert corrected genetic information using synthetic proteins or adenoviruses containing missing genetic information. We are only now in the last two decades starting down this amazing path which will lead to early intervention, even in utero, so that babies will no longer be born with heart and other birth defects.

I personally liked the idea of indulging oneself in the creative activities we love in order to relieve ourselves from any stress. But it is as much important for us to help our kids realize their heart problems. I knew a kid from the park, who was never allowed to play in teams because he was out of breath after only two minutes of running. His parents thought it was a case of improper nutrition and forced him to eat more and more. Until, one day he fainted and was rushed to hospital, only to be diagnosed with a congenital heart disorder.” Little such complaints from kids are often ignored by parents assuming them to be signs of growing up. Hope that after reading this article, you’ll be more attentive to your kids complaints. http://workouttrends.com/symptoms-of-heart-diseases-in-children

Hi Siddarth, My daughter has congenital heart disease diagnosed at birth. The technology to see the genetics associated with such birth defects may soon allow us to repair a defect in utero by splicing new genetic information into a developing baby. The dark side of this progress would be the science of eugenics.