Burial sites in the Eastern Mediterranean from the period around 2000 BCE show evidence of outbreaks of disease that likely contributed to the fall of three great civilizations: the Minoan on the island of Crete, the Akkadian in what is Turkey today, and Egypt’s Old Kingdom.

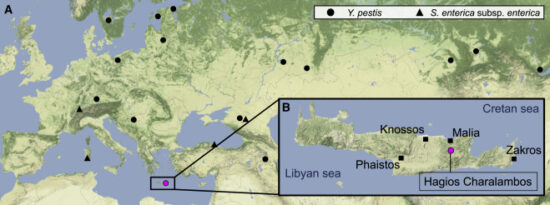

The pathogens found in the DNA of old bones indicate significant outbreaks of typhoid fever and the plague. The emergence of widespread disease in this area of the world at that time may be related to climate change, or pressures from new waves of human migration coming from outside the region. But a paper published in Current Biology on July 25, 2022, shows widespread infections involving the bacterium Yersinia pestis, responsible for the many incidents of plague that occurred in ancient civilizations all the way to the era of Justinian 1st in the 6th century CE Eastern Roman Empire which modern scholars labelled Byzantine. Also found in burial sites is widespread evidence of Salmonella Enterica the cause of typhoid/enteric fever.

This evidence coincides with a period of major geopolitical transformation from 2290 to 1909 BCE. During this time the Old Kingdom, the Akkadian Empire, and the Middle Minoan civilization were all disrupted. The periods are associated with societal and population declines throughout much of the Eastern Mediterranean. Did these depopulating diseases come from elsewhere brought in by migration and invasion? Were there environmental factors such as a change in the climate? Was there degradation of agricultural lands leading to famine, and a general weakening of the local population?

The authors of the published paper argue that the sites point to this being the premier plague of the Mediterranean world joining other pandemics in that region’s history including the plague of Justinian, and the Black Death in Medieval times.

Did these disease outbreaks coincide with a changing climate? Although this new paper doesn’t attempt to draw a link, there is significant evidence that warming periods, external population shifts, local population growth from increased agricultural yields, and increased global trade preceded these pandemics. Is this evidence correlation or causation?

And what can it teach us here in the 21st century as COVID-19 continues to persist contributing to more deaths globally than any plague in the past? The closest analogy in terms of impact would be the Black Death. Our interconnected world today is a vehicle for disease transmission on a global scale. Pandemics in the modern world spread through airline and shipping lanes. And considering that this current pandemic is coincident with rising global temperatures, I ask again, is this evidence of correlation or causation?

The recent advances in genomics and the sequencing of ancient DNA from bones in burial sites are revealing a whole new understanding of the past. A study reported last year showed that remains from a burial site dating from the late Paleolithic/early Neolithic indicated the presence of the plague even back then. And as more old bones are analyzed from burial sites in both cold and warm climates (see the map appearing at the beginning of this posting) it is apparent that epidemics occurred frequently in human populations.

What is not known based on this Eastern Mediterranean study is the carrier that first introduced the diseases to the local populations before human activities facilitated the spread. Were these infections first spread by insects? Were fleas involved?

[…] the human species show that disease and war have played a part in altering the DNA of populations. Disease outbreaks have been transformational. Empires have risen and fallen because of them. Some disease outbreaks […]