February 11, 2016 – The problem with greenhouse gases is they don’t recognize political boundaries. Carbon dioxide emitted in China and the United States impacts the entire globe. In a recent study appearing on Nature.com, authors Glenn Althor, James Watson and Richard Fuller state “20 of the 36 highest emitting countries are among the least vulnerable to negative impacts of future climate change.” They continue, “conversely, 11 of the 17 countries with low or moderate GHG emissions, are acutely vulnerable to negative impacts of climate change.”

Only 28 countries, according to this study, demonstrate a balance between the emissions they produce and the vulnerability they are or will experience. And as global warming continues the research shows the inequality described above will even worsen producing countries described by the authors as “free riders causing others to bear a climate change burden.”

What does this mean in our battle to combat global warming?

If a country is putting out gigatons of greenhouse gases and not being significantly impacted by warming, what incentive is there for that country to lower its emissions? The issue raised here is one of environmental equity even in the face of minimal impacts. For those nations who see little vulnerability to global warming in their future, will that lack thereof create indifference to the issue?

Today the top ten greenhouse gas emitting countries produce greater than 60% of total global emissions. The three biggest are China (21.1%), the United States (14.1%) and India (5.2%). Are these nations vulnerable? Absolutely. On an index between 0 and 100, however, they get a 64% score.

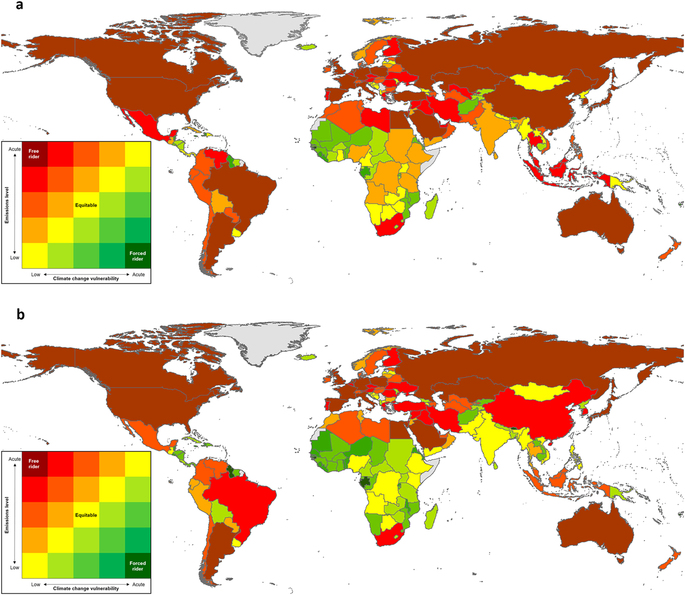

But the island countries of the world’s oceans, plus African countries, contributing very little to greenhouse gas emissions, are acutely vulnerable. From the study I have reproduced the following map.

The world map seen in Figure A shows climate change equity as of 2010. Figure B shows changes by 2030. Free riders appear in brown. The second level of near free riders are countries with high emissions and low vulnerability and they appear in dark red. Countries described as forced riders, those with the lowest emissions and highest vulnerability, appear in dark green. Countries appearing in yellow produce greenhouse gas emissions equal to their vulnerability. Greenland appears grey because there is insufficient data to make a determination.

Today there are 20 countries described as free riders and 90 others with emissions higher than their vulnerability. The countries described today as forced riders number 6 in total. They are Comoros, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Sao Tome and Principe, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. That number will grow by 2030.

The answer to this inequity at COP21 was agreement to commit to financing $100 billion U.S. per year by 2020 to help those nations most vulnerable. But no legally binding mechanism was attached to the commitment and history has shown that funding promises aren’t the same as funding delivery.

It is this latter issue that is being highlighted by today’s meeting here in Canada, (deemed in the study a free rider nation), between our Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, and the UN Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon. The two are expected to talk about climate change among a number of topics, and Canada’s pledge at COP21 to contribute $2.65 billion to vulnerable countries. I suspect the Secretary General will be making similar appeals to other free rider nations in the coming months.

In the study’s conclusion the authors state, “The Paris Agreement [COP21] may be a significant step forward in global climate negotiations. However, as the Agreement’s key policies are yet to be realized, member states have both an exceptional opportunity and a moral impetus to use these results to address climate change equity in a meaningful manner.”

That means holding climate free riders to account to ensure equitable outcomes and the ability of forced rider countries the means to adapt rapidly to climate change.