Last night I listened to Joseph Robertson, Citizens’ Climate International Executive Director speak to CCL Canada members about the importance of Canada in leading by example for the international community in the battle to reverse anthropogenic climate change. From an outsider’s perspective, Robertson described how Canada has put in place a market mechanism for reducing carbon pollution and created a system that allows for local initiatives to accomplish the goals of the national standard which involves a progressive increase in the price of carbon emissions produced at the source with a system of offsetting compensation going back to individual taxpayers. Robertson believes that our asymmetric federal carbon pricing model and the agreement from our provinces and territories, albeit after a number of legal battles, can be the model for a future standard of practice focused on carbon border adjustments among nations. He also noted that words matter, that by not calling it a carbon tax but rather a price on pollution, and by putting in place compensatory policies to offset the cost, the system has become a standard for other nations to follow.

Robertson’s words were spoken as Canada’s federal government was revealing its 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan and a $9.1 billion federal investment to be included in next week’s budget. The plan’s subtitle states “Canada’s Next Steps to Clean Air and a Strong Economy,” a balanced statement appealing to those at the forefront of climate change action advocacy, and those with concerns that any regulatory or financial sticks that come with the $9.1 billion budget carrot don’t negatively impact the country’s economic wellbeing.

The 2030 plan is really the second act in Canada’s national strategy to achieve a net-zero economy by 2050. Net-zero means an economy that offsets any greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) produced by reducing them at the source or using technologies and processes that negate their production.

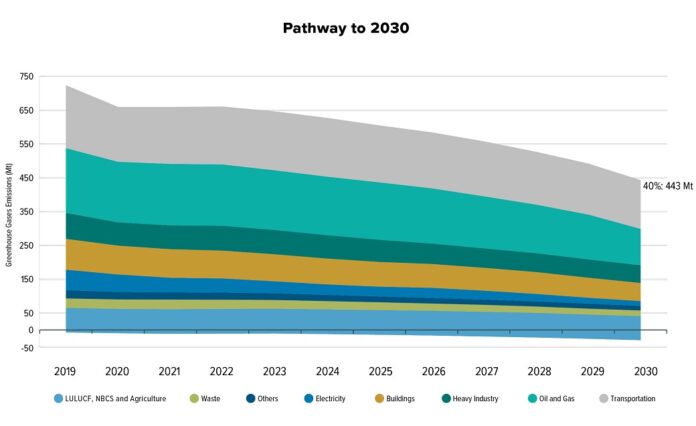

To get to net-zero, the plan sets a 40% reduction target in GHG emissions by 2030 from 2005-measured levels. In preparing the plan, the government site acknowledges that some 30,000 Canadians provided input. I was one of them.

Canada, a country that spans thousands of kilometres both east and west, as well as north and south, has to recognize the regional challenges of the expanse. The remote northern and Indigenous communities have specific environmental, energy, and economic requirements. The same is true for the maritime regions of the country both west, east and north. There are the sustainability challenges of Canada’s growing urban setting where currently more than 80% of the population resides. Farmers across the various geographies of the country have their own particular challenges brought on by the threat that climate change poses to their economic and national food security. The fossil fuel industry, which largely resides offshore on the east coast, and in the Canadian prairie provinces, is the largest contributor of GHGs in the country. The industry’s economic well-being and those employed by it, therefore, need a sustainable path to the future.

Constructing a plan that addresses the range of differences among Canadians, therefore, has caused a number of false starts over the past few years. Supposed to have been tabled by 2020, the global pandemic and the emergency it created in terms of addressing the economic fallout from it, led to a number of postponements.

But now we have it. And what does it encompass?

Most importantly, the principle of putting a price on carbon pollution is now enshrined as policy to continue for the foreseeable future as a constraint on polluting industries, and on the use of fossil fuels for transportation and heating.

All benchmarks as starting points for measuring progress forward will be based on documented GHG emissions from the period beginning in 1990 and ending in 2019. In that last year national carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions topped 730 million tons with the oil and gas sector leading, followed by transportation, housing and buildings, heavy industry, and agriculture. Oil and gas, and transportation from 2005 to 2019 increased emissions by 20 and 16% respectively. The others all showed variable declines.

How the government will measure progress is based on modelling being used internationally. The pathway to 2030 reductions looks at each sector of the economy, their economic interdependencies, and the progress made in each between now and the end of the decade. There will be measurable milestones and interim targets. Failure to achieve them will lead to adjustments in policy and strategy so that each sector can match the model target reductions. The first report is scheduled for December 2022 with following progress to be reported by late 2023. Reports are mandatory biennially (every two years).

In Part 2 of this look at the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan, we will start a drill down on the path that the fossil fuel and energy sectors need to take to keep us on target for 2030 and net-zero by 2050.