Farmers for Climate Solutions (FCS) is a farmer-led organization in Canada focused on how this sector of the economy can provide solutions to address climate change. The focus is on programs and policies that help farmers reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and build climate resilience best practices.

Farmers see themselves as stewards of the land. They are the first to notice the impacts of climate change as even small differences in temperature and precipitation can impact yield amounts and the quality of crops.

Canadian farms are presently responsible for 12% of the country’s GHG emissions coming from practices heavily dependent on fossil fuels for the energy needed for transportation and operations, and for fertilizers and pesticides.

In pursuit of GHG emission reductions, an FCS task force recently completed an interim report with the final one to be released in June that describes the sector at present and offers recommendations to farmers, food industry stakeholders and governments on developing best management practices (BMPs) for climate change mitigation and adaptation. It lists 18 recommendations that Canadian farms can apply to reduce their GHG emissions, increase carbon sequestration, and adapt to the changing climate conditions.

The BMPs recommended for adoption call for Canadian governments (federal and provincial) to provide funds up until 2030 amounting to $1.8 billion in total. Recommendations are organized into six categories: improvements to nitrogen, manure, soil, wetlands, woodlots, and livestock practices. Implementing BMPs gleaned from the best in Canadian farms will allow the agricultural sector to reduce emissions by 11.6 million tons of carbon dioxide by 2030.

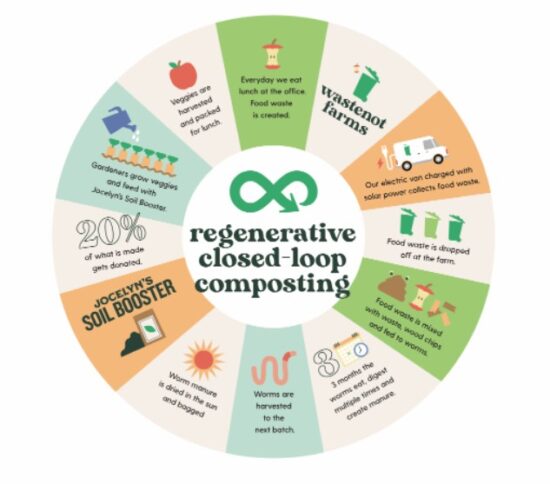

Some Canadian farms are specializing. One such is Wastenot Farms near Caledon, Ontario. Wastenot is diverting organic waste from Toronto-area companies and methane captured from landfill sites to improve manure and soils which have become the farm’s principal products. Wastenot calls itself a vermicomposting biorefinery. If not familiar with the term, vermicomposting refers to a process where earthworms are used to convert organic waste into manure rich in nutritional plant content.

Of course, farming practices are largely determined by geography and weather. Outside Canada, the pursuit of smarter farming practices is leading to creative climate mitigation and adaptation solutions. Here are three examples:

- In Oregon, climate-informed forestry and agricultural practices are being used to lower GHG emissions. Oregon farmers are planting cover crops and using no-till methods, and are allowing trees in forests and woodlots to mature longer to sequester more carbon and create healthier soils and habitats.

- In Costa Rica, small-scale farmers are using microfinancing institutions to help fund climate-smart agriculture, beekeeping, agroforestry, and livestock farming. The western side of the country lies in a dry belt that characterizes much of the Pacific Ocean side of Central America from Panama to Guatemala. The projects are less about climate mitigation than they are about adaptation. Microloans are helping to fund the building of rainwater collection and drip irrigation systems, and greenhouses to reduce evaporation. In the Central Valley of Costa Rica with its highly variable climate, Costa Rica has established an organic fertilizer laboratory that is producing improved soils and seeds. In this more hilly and mountainous terrain, sustainable farming practices include planting fruit trees and perennial herbs on slopes to stabilize soils and reduce erosion.

- And in Mozambique, goats are replacing other types of livestock in areas where climate change is leading to water uncertainty. They are low maintenance and hardy and can survive dry spells, and find nourishment even in failed crops.

Getting back to Canada and the FCS report’s ask of the different levels of government to invest $1.8 billion between now and 2030, that number is less than what is estimated to be the money Canada’s oil and gas industry has received in subsidies coming from federal, provincial and local governments. That number is around $1.9 billion. Which would you say is a better use of the public’s money?