June 1, 2018 – The term “carbon budget” only recently entered the public lexicon. What does it mean?

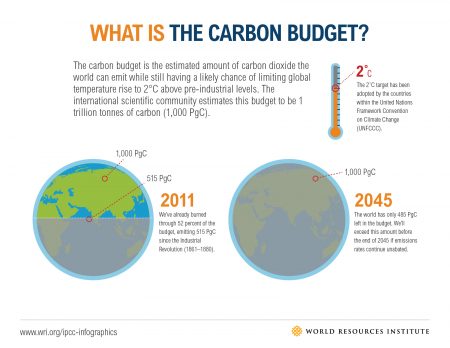

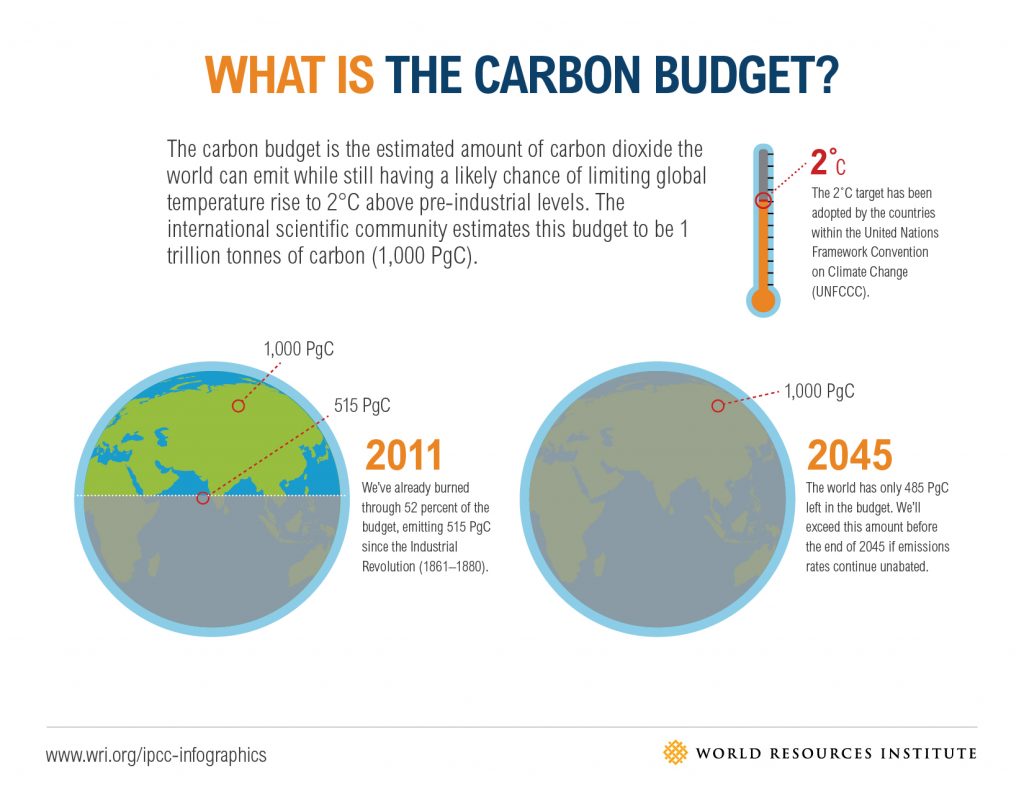

When the nations of the world got together in Paris and agreed to pursue a limit on global warming to less than 2 Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) and preferably no more than 1.5 Celsius (2.4 Fahrenheit), it was accompanied by national pledges on total emissions of 6 greenhouse gases deemed responsible for rising temperatures and increasing extreme weather events. The primary greenhouse gas of concern was carbon dioxide (CO2). Countries looked at the 2 and 1.5-degree limits and their CO2 emissions and determined the amount of the gas they could continue to produce to stay within the targeted temperatures. That meant looking at the source of emissions currently and expected in the future and establishing budgeted amounts of allowable CO2 going forward.

Establishing a carbon budget is not an easy task. You need a baseline to start which means you have to measure all greenhouse gas emissions from all sources in your country. Some of those are natural (forests, farmland, permafrost, wetlands, volcanoes, etc.) And some of those are human-produced (extracting and burning fossil fuels, heating, cooling, transportation, etc.) Distinguishing the source requires sophisticated tools for doing the calculation.

Beyond a baseline, a carbon budget needs milestone dates in the future with acceptable emission volumes tagged to those dates. The effort to mitigate emissions is seen as critical today if the nations of our planet intend to achieve the lower or upper limit Paris targets to which all have agreed. Setting an upper limit on CO2 emissions is only one of a total of 6 greenhouse gases that we need to mitigate. Some of the others such as methane (CH4) could be addressed with shorter timelines through changes to industrial practices resulting in more rapid reductions in total emissions. This has a benefit for nations struggling with CO2 which is a much harder greenhouse gas to deal with. Carbon budget deadlines for CO2 can have longer timelines if other greenhouse gases are reduced sooner.

The easiest way for nations to tackle a carbon budget based on 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius is to look at fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas). Current consumption of fossil fuels and their carbon contribution can be allocated a baseline total by which mitigation efforts can be measured. Similarly, industrial emissions from factories, for example, cement, can also establish a baseline from which mitigation efforts can be assessed. End of pipe emissions from transportation sources can have established baselines as well. The best way to determine a measure would be to have the manufacturers of various transportation (cars, trucks, trains, ships, airplanes, etc.) establish individual baselines right off the assembly line.

You can imagine the complexity in the calculation to come up with the right numbers. That’s why researchers try to simplify the calculation through modeling Earth systems after using satellites and airborne observation platforms to try and establish both the natural and human (anthropogenic) contributions of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Modeling is indeed a simpler way to come up with an overall carbon budget.

Executing a strategy to achieve lower carbon emissions can only start when you know the current numbers. Then the government can set carbon-limits on different greenhouse gas emissions and monitor overall results by measuring amounts in the atmosphere. Less will mean the carbon limit policy is working. If it is not then governments need to get more granular. This can be done by monitoring greenhouse gas emissions at every smokestack and tailpipe, or by determining specific carbon emission content in fuels when combusted at the point of production. Granular would require far greater regulatory oversight.

One way or the other, every nation and its citizens have to make a choice. Do nothing and neither the 1.5 or 2-degree limits will be achievable. At current greenhouse gas emission annual contributions, climatologists see 4 to 4.5-degrees as the rise in global warming by the end of the 21st century. Remember, that is a mean temperature calculation and unevenly distributed over the globe. In places closer to the poles, a mean of 4.5 degrees will turn into an average rise of 15 Celsius or more in places like Alaska, northern Canada, Scandinavia, and Siberia. We have yet to produce models to show us what that will mean to the flora and fauna that live in these areas of the planet. Nor do we know what that will mean to changes in the permafrost and the greenhouse gases we know that are trapped in this no longer permanently frozen ground.