October 13, 2015 – My daughter was born with congenital heart disease. I’ve written about her complex heart lesion in the past. Because of it she has had to undergo three heart procedures. The first two were open heart. The third was minimally invasive using a catheter. All repaired the heart. The first two meant weeks of hospitalization and long recovery periods lasting months. The last one had her home in three days and back at work within two weeks.

Cardiac catheterization is a technology first conceived in 1929 and implemented in clinical practice starting in the 1940s. Initially a diagnostic tool, catheters (thin tubes) were inserted into a vein or artery in the arm or leg and threaded guided by x-ray into close proximity to or inside the heart. Using contrast dye injected into the heart and blood vessels through the catheter, doctors were able to see their structure two-dimensionally. This was revolutionary for diagnosis.

But in the 1960s catheterizations evolved beyond diagnosis and became useful as a compliment to surgery. Doctors started using them to change the internal blood flow. A catheter could poke a hole where needed. Or it could be used to carefully open a blood vessel. But this really didn’t get going until the 1970s when catheters with inflatable balloons were first used to open blocked coronary arteries. By the 1990s interventional catheterizations were common practice in hospitals around the world.

Devices of all kinds from stents (little wire mesh structures that could be embedded in blood vessel walls) to patches were among the many tools that doctors could now insert into patients. No need to cut open the patient. In the case of my daughter’s last procedure she received a pulmonary valve that was inside a stent. When implanted through a balloon catheter the stent was opened up and with it the bovine valve. It meant she could avoid another open heart surgical procedure. It’s now six years and she’s been going strong with her new valve.

But it gets even better. In the last month researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital and the Wyss Institute of Harvard University announced the next generation of catheterization technology, a specialized catheter for repairing holes in the heart using biodegradable adhesive patches. Their research is reported in an article entitled, “A light-reflecting balloon catheter for atraumatic tissue defect repair,” in the September 23, 2015 issue of Science Translational Medicine. The new catheter and adhesive features several innovations. The former features a balloon with a highly reflective surface and an ultraviolet pinpoint light source that can be directed to a a specific site. The latter a patch containing a biodegradable adhesive coating.

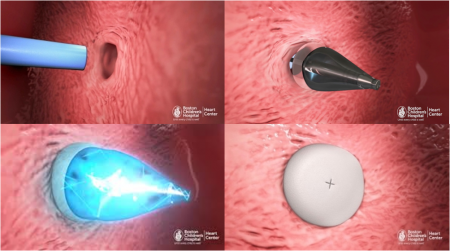

During a procedure such as the closing of a septal defect (a hole in the heart wall separating the organ’s pumping chambers), the catheter tip is directed to the repair site. The patch is deployed and the ultraviolet light source is switched on. The light reflects off the balloon surface. This activates the adhesive coating in the patch. The glue then cures. The balloon is deflated and the catheter is removed. The patch takes less than five minutes to cure. The four images below illustrate the procedure. The upper left shows the catheter insertion. The upper right the deployment of the balloon on one side of the hole. The lower left shows the adhesive patch being deployed and bathed in ultraviolet light to cure it. The lower right shows the patch after removal of the catheter.

The remarkable, light-activated adhesive agent is a product of Gecko Biomedical. It is highly viscous and hydrophobic making it capable of working in wet environments such as the inside of a blood-filled beating heart. Fully biodegradable and elastic so it conforms to the tissue surface to which it adheres, and once in place the patch gets replaced by the body’s own cells which grow over it as it dissolves. The biodegradable rate is adjustable for patches that need to be in place for a longer period of time to ensure viability of the repair. In the end the heart is left with no foreign materials that can become places where bacteria can collect leading to endocarditis (inflammation of the lining of the heart).

“This really is a completely new platform for closing wounds or holes anywhere in the body,” states Conor Walsh, Assistant Professor of Mechanical and Biomedical Engineering, Harvard Biodesign Lab. The potential for the technology’s use in repairing internal wounds goes far beyond cardiology. The variable rate of biodegradability makes the adhesive patch usable for all kinds of procedures. As for cardiology the technology is revolutionary, further extending the use of minimally invasive procedures to replace complicated open heart surgery which usually involves stopping a beating heart and going on bypass machines to maintain life support.