August 3, 2016 – In March 2016 scientists from the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) used computer models to predict where Zika transmission through mosquitoes would impact the United States. Miami was first on the list. The reason, the city had the right summer climate and breeding conditions for Aedes aegypti. When I wrote last week that 4 cases of mosquito-transmitted Zika had been identified in that city I knew this was the tip of the iceberg. As of today the number has risen to 15 and unfortunately will continue to grow spreading through mosquito contact in as many as 50 U.S. cities in the lower half of the country throughout the rest of this summer and into the fall.

The Center for Disease Control in Atlanta has predicted that the range will extend from California to Utah, Denver, Kansas City, southern Illinois, Indiana and Ohio and from there to New Jersey, New York City and Long Island. In March CDC Director, Tom Frieden was quoted in the Associated Press stating, “there are more places at risk than realize they’re at risk, given where the mosquito is likely to be present.”

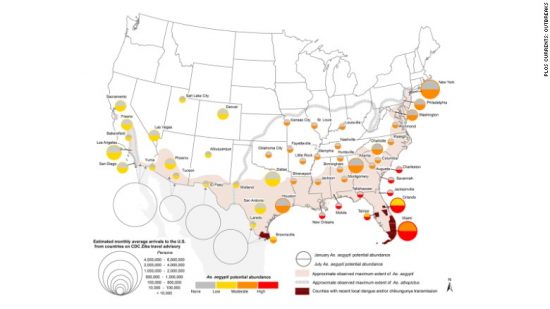

The extent of the threat is best presented in the following NCAR map which appears in a research article that was published way back in March. It appeared in the scientific journal PLOS. The map shows the suspected range of Aedes Aegypti and Zika virus in the continental United States for 2016 based on two simulations. The various sized circles represent cities within the identified range and the number of air travelers on average per three months that will be arriving from identified Zika-outbreak countries. All locales shown on the map are meteorologically suitable for the mosquito to breed with the most significant geographic transmission inhibitors the Appalachian and Rocky Mountains. Proximity to the ocean was also seen as a factor in the spread.

Based on the simulations they showed August and September as being the peak of the spread with the Gulf states the area of highest outbreak concentration. Note the hot spots appearing in deep red.

Cities most at risk include Miami, Orlando, Tampa, Jacksonville, Tallahassee, Savannah, Charleston, Mobile and New Orleans. Cities at moderate risk include New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Kansas City, Oklahoma City and Houston. Winter should confine the risk to Southern Florida and a small portion of the Texas Gulf Coast and Rio Grande valley. Over winter the threat is deemed moderate.

In the past Aedes aegypti was thought to be found exclusively in urban locales in the Gulf states but changes to precipitation patterns and temperatures in recent decades, attributed to global warming, has extended the insect’s breeding range.

As for the potential threat of Zika spreading from athletes and tourists heading to Rio de Janeiro, a mathematical model created by epidemiologist, Mikkel Quam, shows that August will not be as much of a threat as some suspect. Quam states that the cooler and drier conditions of winter in Rio will lead to about 4% of Olympic attendees getting bitten by Zika-carrying mosquitoes. The calculation amounts to 1 in 31,000 among 500,000 game attendees getting infected. That tabulates to 16 cases of Zika from the Olympics.

Zika pandemic modelers, therefore, predict that the Olympics will not play a significant role in its global spread. States, Alessandro Vespignani, of Northeastern University in Boston, “there are already so many cases around the world that adding a little bit more cases is not going to make a difference at this point.”

Of course the almost 200 scientists who signed a letter to the World Health Organization a few months ago continue to disagree describing the running of the Olympics in the face of a global pandemic as being “ethically dubious.”