March 10,. 2016 – China wants to mine the Moon. Russia wants to establish a permanent lunar colony. And now even SpaceX sees Americans returning to the Moon as a more realistic goal.

I was twenty years old when Apollo 11 landed at Tranquility Base. Today I am 67 and, in all of my speculations, would never have guessed that the three years and six flights of the Apollo Program would be the sum extent of human exploration of our nearest celestial neighbour. Like Stanley Kubrick, whose film 2001: A Space Odyssey included human presence on the Moon, I too believed by now we would be permanent residents.

The race to land on the Moon was a child of Cold War politics. Once won the Moon lost its panache and human presence in space descended to low-Earth orbit missions. The old Soviet Union and the United States eventually established a tenuous partnership based on near-Earth missions. The Soviets built the space station MIR. The Americans launched the shuttle. Eventually they agreed to cooperate along with other nation partners in building the International Space Station (ISS). When the Soviet Union disintegrated there was no longer a raison d’etre for competition in space. That is until the Chinese showed up with their own program of human missions to low-Earth orbit.

But for a brief time back in 1969 the United States was considering a more “Kubrickian” future of human missions to the Moon to establish a permanent lunar base. A task group established by President Nixon considered three options:

- a century-end human mission to Mars

- a sped up mission to the Red Planet by 1986

- a lunar colony.

None of these initiatives gained traction or financial backing. Real politics got in the way.

When George H. W. Bush became President the idea of a Moon colony was revived with plans for a permanent base by 2009 to be followed by a mission to Mars in 2019. Under President Bush’s son, George W. contemplated a return to the Moon by 2020. But this too was shelved when President Obama came to office. Since then the United States through NASA has talked about a return to the vicinity of the Moon but not its surface. The idea is to do a series of Deep Space missions beyond the Moon establishing long-term habitability at Lagrange Points above the Moon’s dark side.

Going back to the Moon permanently has always been seen through the eyes of national space agencies like NASA, Roscosmos, and ESA, with big budget numbers the main detractors to any action. NASA now has its sights set on a human mission to Mars in the mid-2030s. But not Russia, China or ESA. All three believe the Moon is the logical first step to establish human habitation. That a lunar base would be the test bed for building a permanent presence for humanity off the Earth. On the Moon humans could learn to survive. They could extract water, hydrogen and oxygen, helium-3, and other lunar resources useful in building Deep Space capacity. They could perfect habitats and life support systems.

In the March issue of the journal, New Space, nine articles appear outlining how a lunar base could be established in the near term and at costs considerably less than estimates given by NASA. These articles represent the culmination of a gathering of like-minded individuals at a 2014 conference hosted by Peter Diamandis and Singularity University.

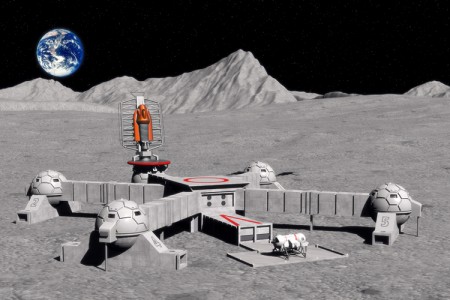

In the first article, Toward a Low-Cost Lunar Settlement, it describes a scenario in which the United States establishes a small lunar base with a crew complement of 10 at one of the Moon’s poles. The base wouldn’t have permanent residents but instead would work like ISS with rotating crews. The permanent residents would be autonomous robots and machines overseen from Earth. But why establish that kind of base when international cooperation among several nations and commercial space operators is already demonstrating success on International Space Station? No one country needs to be taking on the challenge when we already have cooperation among nations and space companies.

In another New Space article entitled, Lunar Station: The Next Logical Step in Space Development, the authors point to ISS as a proof of concept that a long-duration habitation using existing technologies could be constructed on the Moon’s surface. Harvesting best practices from the assembly of ISS would be the blueprint for developing human lunar presence. Not all of the materials needed to construct a lunar habitation would have to be shipped from Earth. Much could be constructed from lunar materials at hand using technologies like 3D printers. Oxygen and water could be harvested from the Moon’s surface. Getting materials to the Moon would mean companies like SpaceX would have to perfect reusability in their launch systems. So far they have only one successful landing of a Falcon-9 after deploying a satellite. And launch capacity would have to be significantly greater. But that too seems to be in development with a SpaceX Falcon Heavy flight planned for later this year, and development of new chemical propulsion systems, a liquid oxygen/methane system called Raptor that will be used by SpaceX to launch even larger payloads to Earth orbit and beyond. Add Bigelow Aerospace and its BEAM habitations, one being tested this year on ISS, and you have the capability to erect inflatable habitations on the lunar surface. Finally, the economics of a lunar base is starting to make sense. Extracting Helium-3 from the lunar regolith alone would make a permanent habitation cost justifiable. Russia through Roscosmos and the European Union through ESA are making similar plans. And so are the Chinese. All are inviting private companies to participate in what is seen as economically viable. What’s more interesting is the estimated cost for a such a settlement housing between 6 and 10 lunar colonists. Not the $100 billion price tag associated with those stillborn projects of the Nixon and Bush years, but rather 1/2oth the number, $5 billion.

Where to settle appears in the New Space article entitled, Site Selection for Lunar Industrialization, Economic Development, and Settlement. With the need to establish a continuous power supply from available sunlight a polar location makes the most sense. The more power generated on the Moon’s surface means the less material needed to be shipped from Earth. Today the cost to deliver a kilogram of supplies from Earth amounts to $100,000. That’s why manufacturing and resource extraction in situ is so important. It simplifies the supply chain making the economy of a Moon base far more attractive.

In choosing between the North and South lunar poles, the best solar return in terms of maximum illumination would be the latter rather than the former. But the terrain of the South is far more rugged and would be harder to tame in establishing a base. So the jury remains undecided. But in any event to ensure continuous sunlight, solar arrays at or near the poles would stand up to 30 meters above the surface to provide a continuous source of light. These poles at the poles would serve a dual capacity providing a means for receiving and sending transmissions to Earth and Deep Space. The technology tested by NASA’s recent LADEE orbiter mission used lasers for communication. Deemed a success, laser communication should provide more than adequate bandwidth for transmission between Earth and a lunar settlement. By adding a space-based relay placing a satellite at a Lagrange point near the Moon, the infrastructure would be even more robust ensuring continuous up and down links and expanding network coverage to off-base lunar vehicles.

Non-human actors would be the principal builders of the lunar settlement. We are talking about autonomous and Earth-controlled robotic systems that would prepare landing pads, design and grade roads, convert lunar regolith into building materials, and harvest water ice from craters for life support and fuel. Robots would deploy the solar and communication towers and as they extended the communication network would facilitate access to even more remote terrain for exploitation.

Once a lunar station gets established, replicating it should become less costly each time. The initial price tag of $5 billion for the first 10 humans would dramatically drop as each new colony was established. The end result would be a lunar economy, largely self sustaining. And with a proven success on the Moon, getting to Mars would be the next big step. But the surface settlement model would be proven and the resources of the Moon would be available to help construct and fuel the journey.

The final question is why should the United States, Russia, the European Union or China do any of this on their own? Why shouldn’t there be a public-private partnership in such an endeavour? International cooperation as demonstrated on ISS has proven itself. All that’s missing in terms of large state actors is for the Chinese to be invited to participate in a joint effort focused on establishing the first permanent human lunar settlement. And why not make this happen sooner by including China in ISS. Doing this would make the lunar endeavour a global one. And lunar success would be the blueprint for Martian success.