November 8, 2013 – Is China on an unsustainable course? Is the pursuit of economic goals leading to an outcome that will make life for China’s citizens an environmental hell? Is China facing what many writers and researchers are calling an “airpocalypse?”

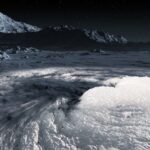

Witness the recent headlines about the smog that enveloped Harbin, a city in northern China. If you are not familiar with the story, in October China shut down Harbin, a city of 11 million. Particulate matter (PM) readings in the air reached 1,000. The World Health Organization (WHO) standard is 20 and anything above 300 is considered hazardous to health. PM indices focus on particles with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers. Harbin’s air (see picture below) was so filled with this gritty soot that visibility was reduced to 10 meters (33 feet) and city buses were getting lost because they couldn’t see their routes. The smog was initially blamed on the beginning of the heating season but it persisted for days. If this were an isolated incident then maybe it could be considered tolerable. But last winter Beijing’s air reached a particulate matter reading of over 900 on one day in January.

Recently the WHO released a report that provided a statistical correlation between incidents of cancer associated with smog-filled air containing PM of 2.5 microns. In addition the report concluded that human lifespans were being shortened by air containg PM levels that today blanket so many of China’s cities.

Although the Chinese government has issued a carbon trading system in its major cities to begin to combat the problem of air pollution, it would seem that economic growth, the continuing mantra of the Communist government, runs counter to its anti-pollution initiative.

Currently the Ministry of Environmental Protection in China lists 4,189 factories and plants as the major contributors of air pollutants in the country. The Ministry claims that these facilities contribute 65% of China’s industrial smog. But what about the growing transportation sector in China and its contribution to pollution? And what about China’s many coal-fired power plants?

But can business as usual continue in China under such brutal environmental conditions? Not likely state the experts including those within China. If Harbin and Beijing’s recent experiences provide clues, business as usual is not possible. Harbin saw the government stop all construction and factory production. Cars and buses were forced off the street. People were told to stay in their homes. Economic paralysis was the result.

China is trying to cut coal use by heavily investing in renewable and nuclear energy. The country expects to double energy capacity by 2030 but how can it do this on renewables alone? At the same time China is considering putting restrictions in place for car ownership by charging congestion fees.

In a recent Massachusetts Institute of Technology study, the researchers concluded that high PM levels from pollutants were expected to reduce the life expectancy by 5.5 years for some 500 million living in Northern China. Michael Greenstone, one of the authors of the study was quoted, “We can now say with more confidence that long-run exposure to pollution, especially particulates, has dramatic consequences for life expectancy.” The study produced a metric that can be applied to any country. For every increased PM reading by 100 micrograms, life expectancy is lowered by 3 years. China between 1981 and 2001 consistently has had PM readings of 400. Compare that to the average in the U.S. during the same period at PM readings of 45. And shorter life spans from air pollution have been equated with reducing the Chinese workforce by one-eighth.

So the China we know today has to make fundamental choices about its future sustainability. Can the economy continue to be the central thrust of the Communist government’s policy? Or does the government have to rethink what is more important, unrestricted growth or the quality of life of its citizens? Greenstone states, “It’s not that the Chinese government set out to cause this….this was the unintended consequence of a policy that must have appeared quite sensible.” That quite sensible policy Greenstone refers to was the introduction of a great deal of private enterprise initiative into the Chinese economy and to develop the energy capacity to support a growing economy.

But back in July the government of China promised to invest $275 billion to combat air pollution. Will it be enough and will it be soon enough to reverse decades of environmental degradation not only to the air but also the land and water?