August 23, 2015 – I’m listening to cicadas outside my apartment window this morning. The steady high-pitched buzz saw singing that often is mistaken by those who are uninformed for the sound of electricity passing through wires. On my morning walks these past few weeks with Maya, my red miniature poodle, it has been hard not to notice cicadas. They always emerge from the ground in mid to late summer, usually overnight. They climb up posts and sheds or crawl to a tree where they shed their larval casing, emerge an entirely different looking creature and after an hour or two fly off.

I’ve seen every stage of this emergence this summer (see image below) and have even picked up a larva or two emerging from the ground to put them out of reach of roving ants and other predators. I’ve watched their exoskeletons split and seen the adult emerge from its prison. I’ve observed them in flight. And I’ve watched them die after a short adult life spent signaling to find mates.

It has made me think about life in general. What evolutionary tricks made the cicada what it is? A life largely spent under ground, in some cases up to 17 years and then a 24 to 48-hour end stage with a dramatic denouement. It blows me away.

We humans may not appreciate just how different life is from the life we live. Our lifespans in North America stretch on average well into our 80s. In some parts of the world, so called “blue zones” people live even longer lives. Centenarians are becoming more common place as we advance through the 21st century. In fact it seems we are at the precipice in the sciences of genomics, meta data analysis and stem cell therapy to extend human life well beyond what we have always considered our natural lifespan. Some time ago I wrote that by the end of the 21st century we may even see the birth of the first human millenarian, a person living 1,000 years.

J. Craig Venter, the first scientist to sequence the human genome back in 2001, is a co-founder of Human Longevity Inc. (HLI), a company focused on helping us live longer and healthier lives. HLI is using the latest advances in our understanding of genomics, the human microbiome, proteomics, informatics, and cell therapies to tackle aging and biological decline. In its investigations the company is also addressing cures for aging diseases – cancer, diabetes, obesity, heart and liver disease, and dementia. The company hopes to build the largest database containing human genotype and phenotype information and through it extend our lifespan well beyond a century.

That’s a far different life experience than most of the species on this planet. The bulk of life is born, lives and dies in periods marked by hours, days and weeks. Look at the cicada with an adulthood that lasts a blink of the eye in the creature’s total lifespan.

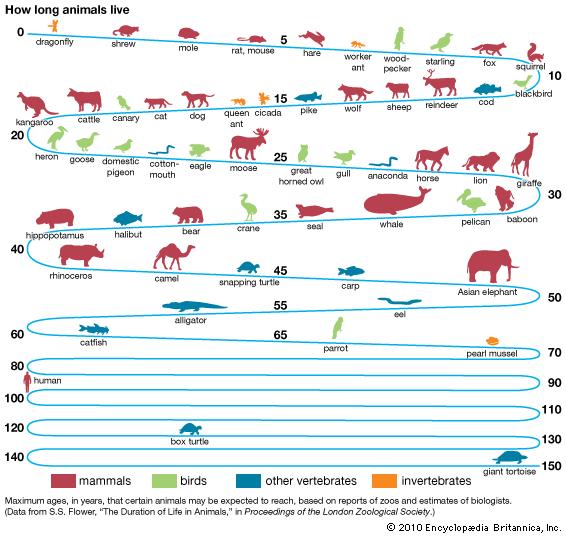

Here are some comparative statistics on the maximum life spans of a number of companion species that share our planet:

- worker ants – from egg to adult up to 12 weeks

- worker honeybees – from egg to adult up to 7 weeks

- fruit flies – from egg to adult up to 40 to 50 days

- Monarch butterflies – 6 to 8 weeks

- dogs – up to 29 years

- horses – up to 62 years

- mice – up to 4 years

- rats – up to 7 years

- Asian elephants – up to 86 years

- Galapagos tortoises – up to 190 years

- Bowhead whales – up to 200 years

- macaws – up to 100 years

The chart below supplied by Encylcopedia Britannica provides a frame of reference on comparative lifespans. Note when you get up to the century mark the number of living species capable of this feat can be counted on the fingers of two hands. And also note the species types bear little resemblance to one another. You have pearl mussels, parrots, catfish, eels, humans, turtles and tortoises.

Note what’s missing from this list. All the micro flora and fauna that if we define in terms of lifespan actually achieve immortality. How can that be? Whether bacteria or a single-celled animal like the amoeba, death of a single cell may occur but through replication all of the genetic information of the original cell is endlessly copied and preserved.

I can still hear the cicadas outside my window as I conclude this posting. I am amazed at the diversity of both life and lifespans from natural selection, from randomness and circumstance over billions of years. It is marvelous to behold and something I wanted to share on a late summer day with the sun shining through the trees casting dappled shadows outside my window.