New Orleans sits on the banks of the Mississippi River. Like so many American cities, it lies close to the coastline of the continental United States. And like so many American cities on coastlines, it is witnessing rising sea levels caused by thermal expansion, and increased melting of polar sea and land ice.

Saltwater is heavier than freshwater. Coastal freshwater aquifers which are often the source of drinking water in cities are increasingly under threat as saltwater invades. In South Florida, cities like Fort Lauderdale and Miami in search of freshwater are tapping the inland aquifers of the state because those wells closest to them are contaminated by saltwater. South Florida isn’t alone in facing this threat. Texas and other coastal communities from Louisiana to New England face saltwater intrusion into their freshwater sources.

Desalination of seawater is increasingly seen as the solution for those areas of the U.S. coast under threat. Current desalination technology, however, remains pricey and wherever it is constructed, poses a threat to marine and freshwater habitats in proximity to these facilities.

New Orleans has a different freshwater challenge than saltwater intrusions into local aquifers. The Mississippi River for the last few years has faced prolonged drought in those areas of the country that feed freshwater into it. The result has been a drop in water levels and a decrease in the rate of flow. New Orleans relies on the river as its freshwater source which is all well and good if the areas from where you draw the water are not compromised by these changing river conditions.

So what is happening near the mouth of the Mississippi River? It appears that with changes to the continental climate conditions of the river’s watershed, saltwater from the Gulf of Mexico is creeping upstream. This saltwater intrusion is a direct threat to the 1.2 million who live in Greater New Orleans.

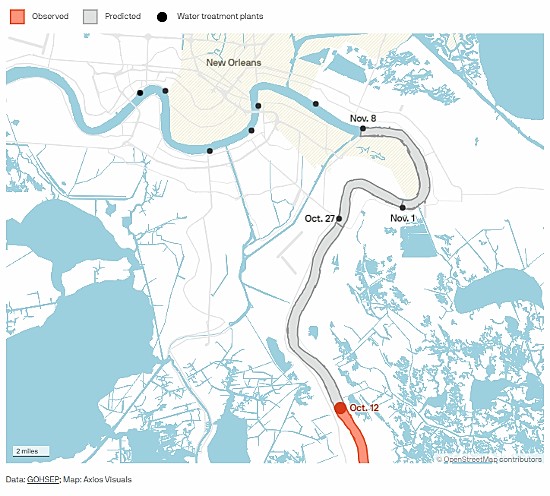

In September, Joe Biden declared the situation to be a state emergency and authorized funding and federal government resources to implement protective measures to secure the city’s water supply. Described as a wedge of saltwater, New Orleans has been monitoring its progress which until a few days ago appeared to be putting most of its freshwater treatment plants under threat. Since then the saltwater has retreated almost 9 kilometres downstream. Conditions inland, however, don’t hold much promise for a return to normal Mississippi River levels and rates of flow. The result is that federal funds and resources will help to build a new pipeline to draw freshwater from further upstream.

The changes in the Mississippi are not all caused by climate change. The river provides for the movement of goods throughout much of the continental United States. Dredging by the Army Corps of Engineers to deepen the river near the Port of New Orleans to accommodate larger ships is enabling saltwater to move upstream. The Army Corps is no stranger to the city and the river. It has been re-engineering the latter since the 19th century. It has built barriers on the river floor to block saltwater intrusion. The latest this year constructed a 7.5-metre (25-foot) barrier on the river bed to inhibit the saltwater intrusion. The barrier failed with saltwater flowing over it.

The new pipeline is a temporary fix because climate conditions in the Mississippi’s extensive river valley and surrounding watershed, according to climatologists, will continue to see the drying of the continental interior.

Tyler Antrup, at the Tulane School of Architecture, who is a green infrastructure expert recently stated “A lot of folks here don’t understand the way that the river works…We’re not expecting everyone to be hydrologists…I think the fact that the primary driver of this event is a drought in the Ohio River Valley is something that is very difficult for an average resident to understand….We need to work on how do we better demystify the whole watershed for our residents because it passes by our front door.” The Ohio River is the main eastern tributary of the Mississippi.

The Netherlands has faced the challenge of saltwater intrusion for centuries. Dutch hydrogeologists point to alternative sources for freshwater supply. These include rainwater catchments, stormwater capture systems, and greywater recycling by homes and businesses to reduce the need to draw water from the Mississippi.

Uprooting the people who live in New Orleans and other coastal communities under similar threat may be, in the end, the ultimate solution as sea levels continue to rise. But it is not our nature to give up on places where humans have established roots for centuries. The Netherlands is a prime example. So I expect desalination and other technologies along with freshwater conservation will help New Orleans get through much of the remainder of this century.