November 25, 2016 – The ice storm that struck Toronto back around Christmas 2013 created levels of personal awareness for most Torontonians about extreme weather. People started asking if climate change was the cause. Toronto politicians suddenly recognized that our tree canopy was a critical tool in the fight against global warming and the heat island effect of the city. A plan to replace the hundreds of thousands of damaged trees was debated at City Council.

This is what I mean by the headline of this piece. Climate change is relevant to individuals when they encounter evidence of it. For towns along Alaska’s coast that are being inundated by rising sea levels, climate change is very real. For the Maldive Islands and Kiribati climate change is personal.

In yesterday’s New York Times, Jan Urbina wrote an article entitled, “Perils of Climate Change Could Swamp Coastal Real Estate.” The question buyers of coastal properties have probably not asked themselves before now is just how far inland should they be if they plan to buy property in Miami or Virginia Beach or Ocean City or Long Island? What’s the magic number of meters or feet above sea level that will ensure they will still have a vacation home to visit or a permanent residence along a coast? What kind of emergency equipment should they be purchasing along with the house to ensure sustainability?

On HGTV, a popular cable channel that includes programming about finding that ideal shoreline retreat there is never a mention of climate change as part of the selection criteria in determining whether to buy a property or not. Think about what Hurricane Sandy did to homes on the New Jersey seashore. Sandy was called a storm of the century but climatologists are expressing a degree of certainty that storms like Sandy will become more frequent and devastating to coastlines particularly along the American eastern seaboard.

Why is that?

The science of climate change points to several factors:

- Ocean thermal expansion – ocean temperatures, not just at the surface, but extending into deeper waters, are rising. Warmer water expands and the only way it can do that is to rise.

- Gulf Stream North Atlantic conveyor belt – the continuous flow of the Gulf Stream combined with a warming of ocean surface water is concentrating warmer water along the U.S. eastern seaboard amplifying sea level rise on the western side of the North Atlantic. Curiously a decline in the strength of flow in the Gulf Stream since 2004 is correlated to acceleration in mean sea level rise along the U.S. east coast.

- Changes in Arctic ice conditions – increases in the melting of sea and Greenland ice is accelerating the rise of sea levels in the North Atlantic.

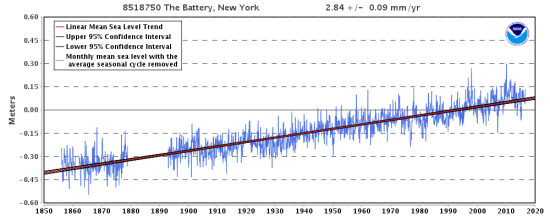

The limits of the science – tracking detailed data on sea levels is a new science barely 20 years old. The older methods of tracking sea level rise can be found in harbor records such as those kept by cities along the coast. For example New York at The Battery has been tracking mean sea levels since 1850. Data (see graph below) shows an average rise of 2.84 millimeters per year or about 1.1 inches per decade.

In 160 years that translates to 0.44 meters or 17.6 inches (almost a half yard). That is not a trivial amount. And when you consider the rate of rise in recent years is accelerating what does that mean for the long term equity in purchasing beachfront property in the Hamptons on Long Island? As a home buyer do you want to spend millions on a place that in thirty years may be seriously impacted by rising sea levels or increased frequency of extreme weather events such as a storm equivalent to Sandy? Yet developers can’t help themselves as they continue to build or rebuild as close to the seashore as in the case of New Jersey and Long Island post-Sandy. One would think there would be an awakening to the potential future costs associated with such behaviour.

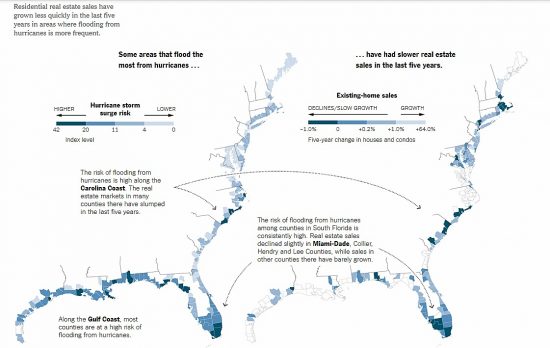

In Urbina’s Times article she notes that maybe the American public is starting to catch on. She writes, “Over the past five years, home sales in flood-prone areas grew about 25 percent less quickly than in counties that do not typically flood, according to county-by-county data from Attom Data Solutions, the parent company of RealtyTrac. Many coastal residents are rethinking their investments and heading for safer ground.” The two maps below illustrate this declining trend over the last five-year period. The map on the left illustrates areas most prone to flooding from storm surges. The map to the right shows the rate of residential real estate sales over the same geography. The alignment of the two in places like the Carolinas and South Florida is unmistakable.

Back in 2014 I wrote about Miami Beach’s ongoing fight against rising sea levels. The neighbour to the larger city of Miami is prone to flooding today. And because the city lacks the ability to raise sufficient taxes other than through property sales, to harden its shoreline it agreed to build 47 new condominiums next to the beach and get the money it needs from these additional buildings which will be under threat from rising seas. As one Florida State University climatologist stated, “When you consider current hurricane threats, and the sea level rise that could erode these properties….Common sense says no, you shouldn’t do it.”

Even Donald Trump has cited climate change in an application to the Irish government for permission to put seawalls along the coast of one of his golf resorts, the Trump International Golf Links & Hotel Ireland, in Country Clare. The application states that the request for permit is required because of “increased erosion due to rising sea levels and extreme weather.” Trump is primarily a real estate developer so even he who denies climate change claiming it is a hoax recognizes the potential peril. And what will be his Southern White House, the property at Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach, sits right along the South Florida shoreline that is considered at high risk to flooding and storm surges.

Urbina writes that Florida has 6 of the 10 most storm-surge vulnerable urban centres in the United States. She cites a report from a real estate data firm that states current tidal floods amounting to 10 per year are expected to increase to 240 per year by 2045. It is, therefore, no wonder that home sales in Miami-Dade County have dropped 7.6% in the past year compared to a national average increase of 2.6%. The annual cost of flood insurance alone is creating buyer reluctance and as premiums rise to reflect true market risk will be a further inhibitor to prospective buyers. It sort of works like an appreciating carbon tax.

And as states change real estate disclosure requirements purchases of shoreline properties may be seen by potential buyers as even more risky. In California, Washington and Pennsylvania today property sellers and their agents must disclose natural hazard risks. But along the Atlantic seashore there is less honesty in real estate dealings. Only a limited area along the Florida coast requires realtors to disclose risks from nature including flooding and wind. When you think about this in a state that periodically is hit by hurricanes, one would expect full disclosure to be a basic requirement. In tidewater Virginia that is not the case. In North Carolina among the 31 disclosure requirements is one question, “Is the property subject to a flood hazard or is the property located in a federally-designated flood hazard area?” There is no follow up to the question asking about the history of the property related to past flooding. Yet in another question about natural risk disclosure it asks about current and “past infestation of wood destroying insects.” I gather termites and carpenter ants are seen as the greater risk when selling a property.

Urbina quotwes George Kasimos, a New Jersey real estate expert who states, “A homeowner may be approved for a $300,000 mortgage with a $3,000 a year flood insurance premium.” But what if the loan is contingent on a $10,000 flood insurance premium. Kasimos sees rising insurance premiums covering natural risks as the most significant factor in reducing interest in the purchase of coastal properties particularly along the U.S. Atlantic seaboard. You can’t get more personal than the fear that you feel when you might lose a $300,000 investment to a rising Atlantic Ocean caused by warming of the water and the air above it.