May 31, 2016 – Some of you who regularly visit 21st Century Tech blog may not know that my academic background is Medieval and Islamic Studies. In my six years at University of Toronto (two years lost to illness and a disastrous accident that nearly killed me) I focused on studying world empires including the rise of Islam and the Mongols.

In 1241 the Mongol Empire reached out to Europe in an invasion that took its armies to the shores of the Adriatic Sea and the Danube River basin. Nothing any European state threw at them could stop their progress. They captured cities and fortresses. Villages emptied and locals fled to forest sanctuaries. Rulers were enslaved and many pledged loyalty to the Great Khan back in Karakorum in Mongolia. The Mongols after plundering much of Eastern Europe set up administrative districts and appeared to be ready to establish their rule over the native population. They organized villages and encouraged the remaining inhabitants to return to farming and cultivating the land. They set up a tax system and placed Mongol tribesmen in positions of leadership over the local population. And then they vanished. Conventional history states that it was the death of the Great Khan back in Asia that led to the summoning of the Mongol armies to return to the steppes of Asia where they would convene to elect a new leader.

But a new research paper suggests otherwise. Authored by Ulf Buntgen, of the Swiss Federal Research Institute, and Nicola di Cosmo, of Princeton University, the paper appears this month in the journal, Scientific Reports. In it the authors argue that “even small climatic fluctuations and time-specific environmental conditions….can have a decisive impact” on historical events.

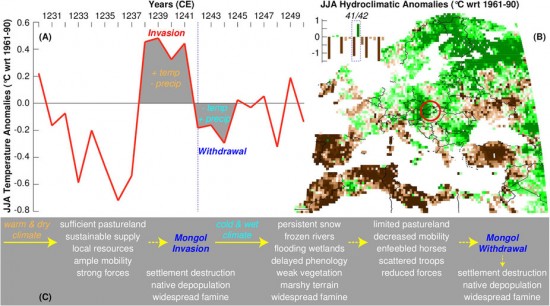

It appears a European climate anomaly may have “done the Mongols in.” The Danubian plain that is the dominant feature of Hungary is normally fairly dry. It tends to enjoy warmer than average temperatures compared to the regions around it because the mountains to the north and west shield it from the worst that European winters produce. But conditions in 1242, the year after the initial invasion, were anything but normal. Paleoclimatological records provide evidence that the invaders experienced considerable challenges as heavy rains then freezing weather and snow, closely followed by an early spring thaw produced poor conditions for maintaining the Mongol’s vast horse cavalry. Those sturdy Mongol horses that survived the Asian steppes succumbed to conditions in Hungary that year. By the end of summer prolonged drought led to crop failures and famine. A diagram from the paper illustrates the climate events prior to, during and after the invasion.

Military historians note that the Mongols conducted most of their campaigns over the fall and winter and used spring and summer for recuperation. This is called military seasonality and in the Mongols’ case bears little resemblance to our normal understanding of warfare. The explanation for this variance is the Mongol reliance on its herds of horses for both transport and sustenance. But the campaign in Hungary in 1242 appears to have been turned upside down by climate conditions. The end result, to avoid a disaster the army reversed its course and turned east in a move in search of fodder for its horses and food for its troops. That turn crossed Serbia and Bulgaria, Transylvania and modern Romania, whose rulers were conquered or submitted to Mongol suzerainty.

So how do we know what the climate was like in Hungary in the period prior to, during and after the Mongol invasion? The evidence comes from paleoclimatological data including tree-ring studies covering a range from northern Scandinavia through to the Hungarian basin as well as year-to-year climate reconstruction from studying peat profiles, alpine glaciers, river sediments, solar radiance and volcanic eruption records. From this evidence the authors conclude that “data presented here support the view that the climatic conditions that occurred in Hungary between 1241 and 1242 had a considerable impact on the productivity of the land as well as on the suitability of the terrain for military operations of the type performed by the Mongols…relying on high mobility and swift storming of fortified places.”

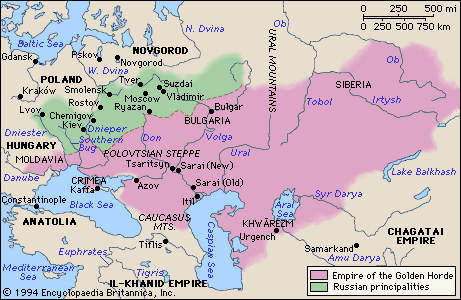

The behavior of the Mongol armies after 1242 lends support to the influence that the climate may have had. Uncharacteristically the Mongols subsequently never returned to Hungary. Instead they established themselves where today Ukraine and parts of Russia exist. They sent armies into Poland and sought submissions from the rulers of Moscow, minor princelings at the time, and eventually created a western branch of the larger Mongol world empire ruled from Karakorum. We know this western Mongol presence as the Khanate of the Golden Horde (see map below) with its capital at Sarai on the Volga River.

Why didn’t they return after the summons to Karakorum in 1242? The leader of the Mongol army at the time, Batu, was one of Genghis Khan’s descendants and the first Khan of the Golden Horde. He never got as far as Karakorum and instead remained in the western steppes of Ukraine and Belarus. So one could argue that the opportunity to expand westward remained. But the authors of this paper argue that the “vulnerability of the Hungarian plains to even relatively short-term climate events made it obvious that the regions was unsuitable for military occupation by a large army relying mostly on horses.” Hence Batu made a conscious strategic decision to avoid uncertain climate conditions and seek greener pastures, a fascinating theory to explain how history subsequently unfolded.

There are some interesting coincidental facts that lend support to this hypothesis. Nowhere else were the Mongols dissuaded from repeated invasions. Even their campaign to conquer Japan in the late 13th century saw multiple attempts. In Southwest Asia Mongol armies invaded Iraq, Palestine and Syria. They overthrew the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. They briefly encountered the last vestiges of the Crusader presence on the shores of the Mediterranean and they engaged the rulers of Egypt, the Mamluk Turks, where they finally met their match, an army that included many Mongol slave mercenaries in its ranks.

When we think of climate change and its modern impact it is interesting to look back and see how human history and climate have interacted. Reading this paper gave me the opportunity to rethink a subject with which I was familiar and I couldn’t help myself in wanting to share its content with you. In a sense I have come full circle in writing this posting, combining my love of science and technology with my academic background. I hope you have found it interesting.