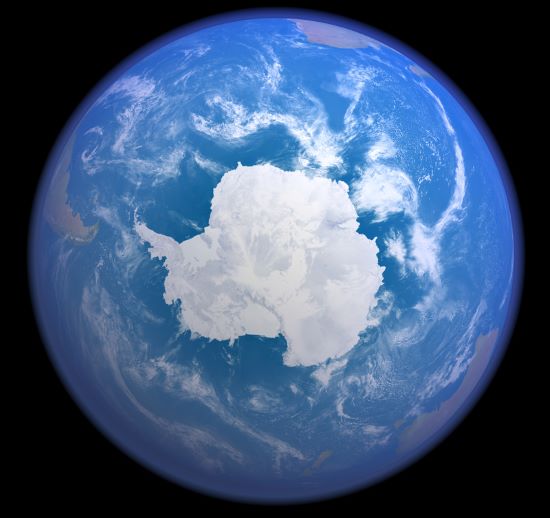

There is lots of evidence globally that alpine ice fields and glaciers are melting at faster rates than we have seen in the past. There is also lots of evidence that the ice sheets covering Antarctica and Greenland are seeing the largest melt ever recorded from human observations in this century and through analysis of ice cores dating back to the last ice advance during the Pleistocene.

All of this meltwater contributes to the rise of sea levels around the world. The Southeastern United States from Tidewater Virginia to the Texas coastline on the Gulf of Mexico bears evidence of how much the seas are rising. Chesapeake Bay provides an interesting example of the dynamic changes caused by continental ice sheets dating from 20,000 years ago, at the penultimate Pleistocene maximum, to 11,700 years ago when North America’s land ice vanished, to the present day.

The phenomenon is known as isostatic rebound or isostatic adjustment. The interior of the continent where the ice sheets lay before melting has been rising for more than 11,000 years and deforming those areas along the edge. That means where some parts of the continent rise, other parts get distorted and fall. This is the same phenomenon we observe when we leave our beds in the morning and our mattresses readjust to not being weighed down by us.

The sections of the North American continent where ice sheets existed including the Northeast and Great Lakes regions are seeing a rise in elevation. The areas on their fringes are experiencing the opposite. In the case of Chesapeake Bay and Norfolk, the continental edge and shelf upon which they sit is tilting downward. That means the land around Chesapeake Bay including the Delmarva peninsula and Tidewater Virginia to the south is subsiding. Combined with ocean thermal expansion and meltwater produced by diminishing sea ice in the Arctic and the thinning of Greenland’s ice sheet, it spells trouble for places like Norfolk and further inland, Washington, DC. Norfolk is home to America’s largest East Coast naval base. Measuring sea level rise there shows it is happening faster than anywhere else on the U.S. Eastern Seaboard. Since 1992, the rise has been twice the global average.

At some point, once the isostatic rebound ends for the areas once under ice, the continent should see a levelling out. But we are talking in terms of geological time which involves thousands to tens of thousands of years. Until then the deformation will continue.

Studying this phenomenon and sea level rise from melting polar, alpine and sea ice is producing some interesting hypotheses. A study undertaken by scientists at Ohio State University published on August 2, 2024, in the journal, Science Advances, has looked at isostatic rebound and global sea level changes into the next few centuries. It concludes that the relatively rapid uplift of Antarctica as its ice sheets melt needs to be accounted for if we are to continue to do a managed retreat from coastlines facing rising seas.

The study begins by stating:

“With nearly 700 million people living in coastal areas and estimates of the cost of sea-level rise reaching ~14 trillion dollars by the end of the century, understanding the future contribution of the polar ice sheets to global sea levels in coming years is of critical societal importance.”

It then looks at what the melting of the Antarctic ice sheets causing isostatic rebound in Antarctica could do to sea levels. The study notes that as the ice starts melting and rebound begins, the uplift can act to preserve the remaining ice and reduce the southern continent’s contribution to rising oceans by as much as 40% over current climate model predictions.

The study further notes that Antarctica’s changing shape could prove to speed up isostatic rebound so that uplifted surfaces from reduced ice volumes happen in decades and not in centuries or thousands of years. In other words, we are no longer working at the snail’s pace of geological time as in the Pleistocene, the Ice Age that preceded the Holocene.

GPS data from the Antarctic ice sheets and North America shows that the isostatic rebound of the former is currently five times faster at 5 centimetres (nearly 2 inches) compared to the latter at 1 centimetre (0.4 inches) per year. Literally, in Antarctica, once the weight of the ice is removed, the continent bobs back up. This rebound is lowering sea levels adjacent to where the ice is melting and may have unforeseen impacts elsewhere on sea levels around the world.

In other studies that look at the combination of melt and rebound another effect has been noted. The two are altering Earth’s gravitational field. A paper previously discussed appearing in Geophysical Research Letters in September 2017, described findings that showed Antarctic ice melt was causing gravitational changes elsewhere while producing enormous volumes of water that were ending up impacting shorelines far removed from the southern continent. It correlated with a 52% faster rate of sea level rise off California and Florida’s coasts equating the cause being gravitational changes occurring from the melting ice and upward bounce of Antarctica’s landmass.

The current research described here includes an expression of the need to do much more research to better understand the complex relationships between the Earth’s crust and the impact climate change has atop it. Scientists need to do more data gathering and research to help us better understand the wide-ranging influences that rising greenhouse gas emissions are having on our world for both the short and long term.

[…] research sheds light on how cratons experience isostasy, a rise similar to isostatic rebound, described previously in articles on this site, the observed continental phenomenon that causes post-Pliestocene formerly glaciated parts of land […]