Malaria, Lyme Disease, West Nile Virus, Dengue Fever, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Chagas, Chikungunya and many other diseases infect humans through insect carriers. Ticks and mosquitoes are the primary disease agents. Birds are secondary agents because they get bitten by insects, host the viruses, and then transmit them to uninfected insects who then bite us. Scientists refer to the infective agents borne by insects and animals as zoonoses.

Where does climate change fit into this disease model?

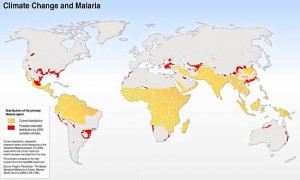

Insects in general are more active in warmer temperatures. Insects like mosquitoes breed in water and when atmospheric heating leads to increased rainfall and standing pools, mosquito populations explode. So warmer and wetter weather means higher rates of human illness and death from insect-borne diseases. Global warming, therefore, means humans previously outside the disease zones are becoming infected as the bearers of these infections migrate and expand their range.

How significant is climate change in the equation of zoonoses? The World Health Organization estimates that an increase in global average temperatures of 2 to 3 degrees Celsius (3 to 5 Fahrenheit) will increase the population at risk for malaria by 3-5% which translates to millions of new infections every year.

The latest alert comes from the United States Center for Disease Control (CDC) which reports in one state alone, Wisconsin, an 70% increase in reported cases of Lyme Disease. CDC admits that the number of reported cases may be 12 times higher. In fact the CDC estimates that zoonoses account for 75% of emerging diseases in the United States.

Insects make great disease intermediaries. Why? Because they have a short life cycle and reproduce often, and although they are cold-blooded, they readily can adapt to variable weather conditions exploiting any positive environmental change.

How significant is climate change in the equation of zoonoses? The World Health Organization estimates that an increase in global average temperatures of 2 to 3 degrees Celsius (3 to 5 Fahrenheit) will increase the population at risk for malaria by 3-5% which translates to millions of new infections every year.

In North America the winter of 2011-12 has virtually been non-existent for much of the continent. What does this mean for the spread of insect-borne diseases? Unfortunately, an increase in the area in which these diseases get reported. And as climate change alters the weather patterns leading to prolonged drought in areas like the Southwestern United States and Northerm Mexico, some insect-borne disease native to those regions will disappear and migrate north. The CDC and Health Canada are tracking the spread of diseases formerly unheard of in the northern U.S. and Canada. Among these is Lyme. At the current rate of range expansion of 46 kilometers (32 miles) per year, incidents of Lyme will certainly increase. Canadian researchers note that the average annual temperature in Canada over the last 60 years has increased by 1.4 degrees Celsius (2.5 Fahrenheit). This is putting more of the population of the country within Lyme’s range, a growth from 18% of the population to 80%.

Human migration is further contributing to new insect-borne disease population patterns. Chagas, previously confined to South and Central America, is rapidly becoming a concern in both the United States and Canada because of a large influx of Latino immigrants. And Chagas is far more insidious a disease. Spread by the Kissing Bug, most infected humans appear asymptomatic at first but 10 to 20 years after being bitten develop cardiovascular symptoms.