With the meetings in Doha, Qatar, coming to an end, is there a successor to Kyoto on the global community horizon? Kyoto was an abject failure but at least it identified strategies for curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Countries that signed the accord in the Developed World, for the most part, achieved the limited treaty goals. But Developing World countries were excluded from having to keep emissions under control. That’s where Kyoto proved to be an absolute failure.

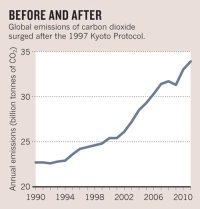

Fossil fuel consumption (particularly coal) continues to increase the volume of CO2 entering the atmosphere. As the graph displayed below shows, Kyoto had no impact on CO2. Only the recession of 2008 caused a slowdown in the upward curve.

Kyoto wasn’t just about CO2. It also attempted to establish curbs on the growth of methane, nitrous oxide, sulphur hexafluoride, hydro-fluorocarbon and per-fluorocarbon. The accord gave license to some countries who were party to it the right to increase emissions while other countries agreed to cap and reduce their contribution of greenhouse gases. A cap and trade system was put in place but even signatories like the United States and Canada did not institute this system of controls.

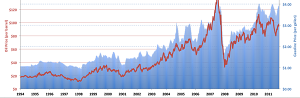

Kyoto was built on a false premise – that fossil fuel increasing scarcity as we entered into the 21st century would naturally impact CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions. But in fact that has not been the case with proven reserves and reserve estimates increasing to the point where the world is awash in oil, natural gas and coal. And even though the cost of oil has generally increased since Kyoto (see graph below), consumption continues to grow.

So where do we go from here? At Doha 200 countries are meeting to discuss the next steps. Delegates have listened to reports from scientists that show rising greenhouse gases and relate Greenland and Arctic ice melts, rising sea levels, and ocean acidification to changing levels of CO2. If all the countries agree to extend Kyoto past the December 31 deadline it will not be a victory for our planet because the protocol, as we stated above, has been largely a failure.

Any new target agreement must recognize that current emission levels need to be capped within the next decade if we are to limit human influenced global temperature rises. That means all countries need to buy into cap and trade and the funding of emission reduction projects including increased research and development on green renewable energy projects. It means investing more heavily in energy conservation than ever before for countries in the Developed World. It means establishing financial resources to assist Developing World countries with their energy needs as they attempt to improve their lot. And it means making these commitments in a period of economic uncertainty in Europe and North America with economies awash in red ink since the recession of 2008.

Every country on the planet will need to cut emissions. Some have set 2020 as the start date for this effort with no distinction between have and have-not countries. We have less and less wiggle room and can no longer punt the ball down the road hoping the next generation can pick it up and score.

Update to this article:

The Doha conference on climate change agreed on December 8, 2012, to extend the Kyoto Protocol to 2020.

In addition the attendees agreed to the following:

- To postpone discussion on the financial needs of Developing World nations to help them cope with the consequences of global warming.

- To adopt by 2015 a wider treaty to apply to all countries including those not currently signatories to Kyoto.

The United States has never implemented Kyoto. Neither has China. And my country, Canada, withdrew from Kyoto in 2011. Let’s hope that sanity prevails and the nations of the world get their acts together.