April 15, 2017 – What separates the rich from the poor these days is looking more and more like technology. The rise of Silicon Valley and its billionaire entrepreneurs coincides with a growing gap between rich and poor.

Technology was always seen as a means to raise all out of poverty. The phrase “raising all boats” comes to mind. It is one used by those who have achieved high levels of success through technological advancements. But the boats aren’t all being lifted when one starts looking at labour data and income. it is not proving to be true for the most part. Yes, a farmer in East Africa who possesses a smartphone and cheap Internet access is better informed about the larger world. And he or she can find out the latest prices for crops being grown. It is also true that Google and other Internet resources bring information to the masses as never before.

Yes, a farmer in East Africa, who possesses a smartphone and cheap Internet access, is better informed about the larger world. And he or she can check on the latest prices for crops being grown which may mean boats will get lifted here.

And it is also true that through Google and other Internet resources, information is now disseminated to the entire planet in an instant making it possible for knowledge sharing on a global scale. Knowledge shared provides the means to opportunity.

But there is a darker side to the technological advancements of the 20th and 21st century. Automation and innovation are stranding many workers, eliminating not only front line, manual labour but also many middle-tier jobs. In blue collar U.S. states, coal miners no longer are needed. Warehousing operations and manufacturing assembly lines no longer need the number of workers used in the past.

The rise of the age of computing, its evolution to the Internet, the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), and the development of robotics, coincide with flatlining in wage growth in the U.S. and other advanced industrial countries. And although these innovations and inventions are making a small minority extremely rich, they are leaving many behind. The growing disparity between the rich and the rest of us is palpably visible.

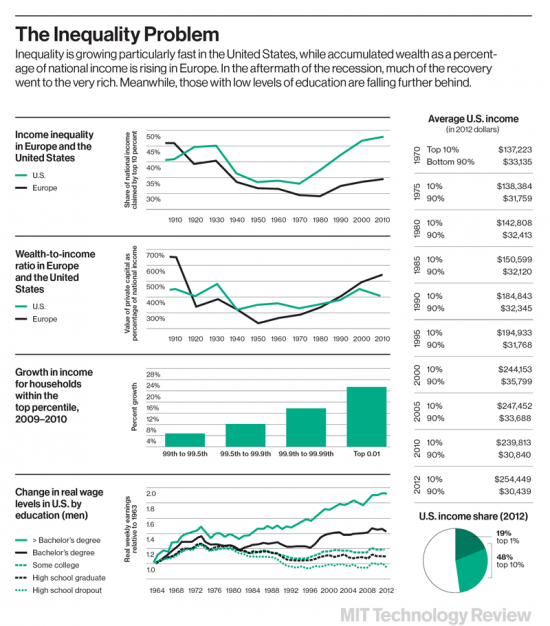

I share with you some interesting U.S. statistics:

- In 2010 the richest 1% in the country controlled 34% of the total personal wealth.

- 0.1% controlled 15%.

- From 2009 to 2012, the top 1% received 95% of the total income growth.

- Presently, the top 10% in earnings represent just under half of total personal wealth.

- The top 1% represent 20% of the total personal wealth in the country.

- And the top 0.1% represent 9% of that total.

The chart below, which appeared in the MIT Technology Review back in 2014, compared income inequality between Europe and the U.S. Although the disparities in Europe were less than that seen in America, the general trend reflected a common correlation. The vast majority of people in advanced economy countries were not experiencing the rising of all boats equally. Income disparity between the bottom and top was widening at a significant rate.

Chief Economist for The World Bank, Kaushik Basu, has written that in high and middle-income countries “total labour income as a percentage of GDP is declining across the board and at rates rarely witnessed.” In a report to The World Bank, Basu points to drops in labour income from a number of example countries covering the years from 1975 to 2015:

- For the U.S. a drop from 61 to 57%,

- For Australia from 66 to 54%,

- For Canada from 61 to55%,

- For Japan from 77 to 60%, and,

- For Turkey from 43 to 34%.

Whereas developing countries on the receiving end of automation and technological innovation have experienced to some degree the lifting all boats phenomenon, Basu believes the effect will be short-term. Basu believes what has happened in advanced economies will also occur in developing states, and writes, “as the march of technology continues, these strains will eventually spread to the entire world, exacerbating global inequality – already intolerably high – as workers’ earnings diminish. As this happens, the challenge will be to ensure that all income growth does not end up with those who own the machines and the shares.”

Innovation and technological advances have created a new working class, particularly among those entering the workforce in advanced countries today. These young people are part of the precariat class. The definition of their economic state is represented in the name. They are precariously employed. They experience unpaid internships, and part-time or contract work. Today in Ontario, where I live:

- 22% of all jobs are classified as precarious with low hourly wages and no benefits.

- 33% of part-time employees are also receiving low wages and no benefits.

- Conditions of employment are such that precarious and part-time workers are experiencing higher risks caused by greater stress from job insecurity, a need to hold multiple jobs to meet basic needs, and the impact of irregular hours on overall health.

The growing gap in income, declining opportunity for those in the workforce where jobs are vanishing, and precarious employment among those entering the job market is a recipe for disruptive change across the board. One can point to the lack of economic opportunity and a future of despair for the political and social dissent that led to the Arab Spring that began in 2011, or the Brexit vote in 2016, or the election of Donald Trump in November of last year. It may fuel the rise of new authoritarian regimes around the world, and to new wars.

Back in the 18th and 19th century, technological innovation created more wealth and sparked explosive growth in employment with the attendant rising of all boats. But John Maynard Keynes back in the 1930s foresaw what he described as the future disease of technological unemployment as automation reduced the need for labour. Today we are infected with the disease.

One remedy may be a universal basic income (UBI) for all citizens. Back in December, I shared with you, my readers, the thoughts of Peter Diamandis on this very subject. Diamandis referenced a Canadian UBI experiment in one small Manitoba community, conducted from 1974 to 1979, that indeed did raise all boats.

Diamandis describes UBI as a needed social policy to counter the consequences of innovation and technological advancement. Why? Because he points to a McKinsey study which predicts 45% of all current jobs will be automated within the next 20 years. McKinsey isn’t alone in foretelling this future.

So maybe ending the growing disparity between the innovators and inventors that bring us technological advancement, and the rest of humanity, by governments instituting progressive social programs, like UBI, will alleviate poverty and raise those from the bottom of the earnings chart to levels of sustainability, and possibly give the UBI recipients the time and opportunity to become innovators and inventors themselves.