August 31, 2014 – As we waited for the gate to open for the Buffalo Bisons-Pawtucket Red Sox baseball game last week on the last evening of our vacation, I noticed a gentleman nearby wearing a Chincoteague Island t-shirt. Sherry and I have been to Chincoteauge and its sister outer banks island of Assateague several times. Both hug the shoreline of the Delmarva Peninsula crossing three state boundaries, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia.

So naturally curious I asked the gentleman when he had been to Chincoteague. It turns out he and his wife had just come back from there after spending two weeks on vacation renting a beach cottage. And that led to a further conversation about the changing nature of the American Atlantic coast as sea levels continue to rise, a fact attributed to climate change.

The gentleman told me that they took a boat ride along the coast and their guide pointed to a house sitting hundreds of meters offshore completely isolated from the barrier island. The guide told them that just a few years ago that house was part of the island but erosion and rising water levels had cut it off leaving it sitting on its own.

It was this tale that reminded me about a recently released report from the National Research Council in the U.S. which describes a dramatic rise in property losses along the entire Atlantic coast from Maine to Florida.

Hurricane Sandy showed us how the combination of rising sea levels and an extreme weather event can lead to devastating loss of property and shoreline. The question then becomes should the focus be on rebuilding what has been lost, or coming up with a different strategy.

Assateague Island is one of many barrier islands on the Atlantic coast that could disappear in the near future, maybe a century, maybe longer. There is little built on this island. It is home to a herd of wild quarter horses first established on the island as survivors of shipwrecks or as contraband livestock hidden by mainlanders trying to avoid colonial taxes. They’ve been on Assateague since the 17th century. And here they have survived and thrived. But within a century their home may disappear into the Atlantic like so many of the barrier islands along the U.S. eastern seaboard.

A new study entitled Atlantic National Seashores in Peril – The Threats of Climate Disruption, published by the Rocky Mountain Climate Organization and The Natural Resources Defense Council, describes the threat to Cape Cod, Fire Island, Assateague, Cape Hatteras, Cape Canaveral and other Atlantic sites. The report shows that Assateague has seen average temperatures rise 0.5 Celsius (0.8 Fahrenheit) degrees since 1971. Projections to 2090 indicate average temperature increases of 3.4 Celsius (6.2 Fahrenheit) degrees. But along with rising temperatures we will see a far more active atmosphere and that means stronger Atlantic storms accompanied by storm surges. Assateague has been identified as one of the “hot spots” for higher storm surges. Now add another threat to the list. Assateague has also been identified as an island particularly susceptible to rising sea levels with a very high vulnerability rating.

In 2010 Assateague Island visits contributed $142,650,000 to the local economy and was visited by over 2 million. It’s wetlands and sand dunes covering over 53 kilometers (33 miles) provided a home for the herd of wild ponies, a sea turtle sanctuary and hatchery, and a thriving environment for seabirds.

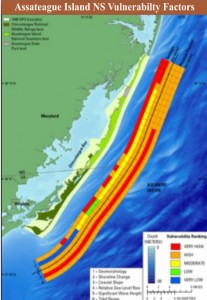

The story about that home now lying isolated offshore from Assateague is not uncommon along the Atlantic coast of America. Beach erosion, overwash from storm surges, flooding, marshland dessication are all happening now. A recent map from the U.S. Geological Survey ranks areas of Assateague most vulnerable to all of these occurrences. You can see by the red indicators those areas along the shore most likely to succumb to one or more of these events.

And although Assateague is less impacted by hurricanes than other eastern barrier islands the tracking of local sea level rise is much greater than the global average making it even more of a hot spot. Recently Assateague suffered numerous breaches from storm surges. Such an incident occurred to the gentleman with whom I was speaking who suddenly found his afternoon at the beach cancelled by an overwash.

A recent study using a modeling program known as SLAMM (Sea Level Affecting Marshes Model), and commissioned by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, concludes that “nothing less than a wholesale transformation of the refuge” will occur. “Vast swaths of wetlands, and the precious shorebird habitats contained within, would likely be radically altered – or even under water – in 2100….producing a cascade effect on the refuge’s habitats.”

To lose Assateague Island in all its beauty is an indictment against humanity. We have already set the course for its destruction. But we can mitigate further destruction beyond 2100 if we pay more than lip service to the issue of carbon reduction.

By the way we enjoyed our evening at the ballpark even though the Bisons lost the baseball game. But I must admit the conversation that preceded lingered in my mind well after. Hence this posting.

[…] A Conversation About Vanishing Islands Before a Baseball Game […]