When Charles Darwin first postulated his theory of natural selection leading to species evolving, his conclusions came from observing the tortoises and finches of the Galapagos Islands. While there he noted that both tortoises and birds showed differentiations from island to island. How quickly these differences arose was an unknown.

Although the molecule of life which we later called deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) had been discovered, Darwin had no idea how it worked. Nor did anyone else until the middle of the 20th century.

Today we know that changes to DNA govern natural selection. Mutations happen with great frequency in most species at the molecular level. Most of the time these mutations amount to nothing much. But sometimes they are transformative.

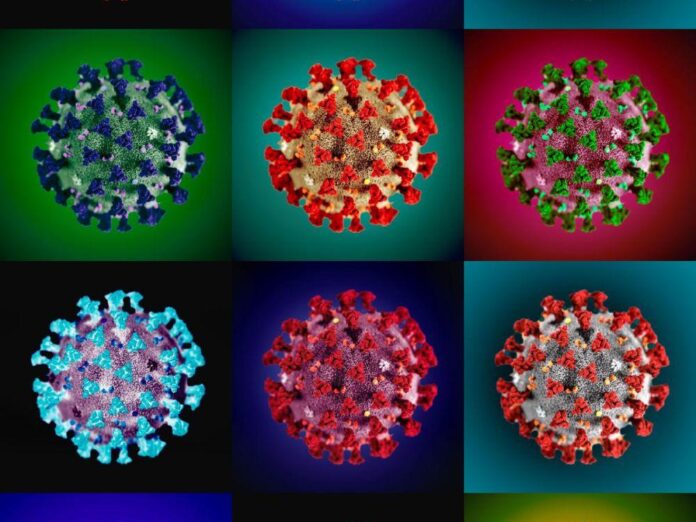

For more than 7.5 billion humans evolution appears to be a slow-moving mechanism. But for quadrillions of viruses, mutations leading to significant variations is common. That’s what we have been observing with the evolution of SARS-COV2 (COVID-19), a coronavirus that has created the current global pandemic. First, the virus mutated in jumping from its host animal species to humans. After that, with conditions optimal for transmission, it has spread around the world at jet speed, finding humans a great breeding ground for natural selection to occur.

When I was infected with COVID-19 in April of 2020 it was the first variant that predominated. Named D614G, it exhibited a spike protein used to attach to human cells. Now it is November, more than a year-and-a-half later, and COVID-19 has run through a Greek alphabet of variants from Alpha through Delta (the current predominant variant) to Mu.

What differentiates COVID-19 from other endemic viruses that humans have learned to co-exist with, is that it hasn’t yet adapted to that point where it can live in us without killing us. Because, ultimately, there is no evolutionary advantage for a species to kill its host. That’s why most of the microbiome within our bodies which makes up more of us than our bones, muscles, and organs have found us to be a benign host in which to thrive.

Scientists describe the interaction between infectious agents and hosts as an arms race. Right now, we have begun to stem the invasion through the rapid development of vaccines and medications. But, as of yet, co-existence is not where we are.

It may be only a matter of time, however, before the current pandemic which has infected more than 257million and killed over 5 million, turns into a seasonal endemic like four other coronaviruses we co-exist with today. These four are HCOV-229E, HCOV-NL63, HCOV-OC43, and HCOV-HKU1, and are responsible for upper and lower respiratory tract infections we associate with the common cold, although the cold we know is caused by a rhinovirus. All of these coronaviruses originated in host animals, whether bats, pigs, cows, or camels, before mutating to leap to human hosts. One thing is for sure, coronaviruses continue to show astonishing interspecies adaptability.

As we continue to perfect vaccinations and medications to combat COVID-19 in all its variants, scientists believe we will eventually achieve an equilibrium, a point when the virus and its hosts interact much the same way as the relationship we have today between influenza and us.

Humans today can get an annual flu shot to help us resist the influenza variants that emerge each year around the planet. Flu kills as many as 650,000 globally each year. Compare that to COVID-19 at more than 5 million dead in 18 months.

And should COVID-19 evolve to be more like other coronaviruses, we may experience the adage, three days coming, three days here, and three days going and resolving without treatment, an infection that seldom leads to the death of its hosts.