At Virginia Commonwealth University’s Smell and Taste Disorders Center, two researchers, Dr. Richard Costanzo and Dr. Daniel Coelho are working on the development of a bionic nose. Costanzo was recently awarded the Max Mozell Award for Outstanding Achievement in the Chemical Senses recognizing his contributions to this field of research which usually doesn’t make headlines. But COVID-19 has put a new focus on the subject because many infected with the virus have lost their sense of smell. For some it is temporary but for others it is permanent. Therapies to treat their loss have included steroid injections, nasal sprays, stem cells, and attempts to retrain nasal senses through electro stimuli. But Costanzo believes the answer lies with technology. The end results are early-stage neuroprosthetic bionic noses designed to detect everyday odours.

Losing your sense of smell is a big deal. As we age it happens to many of us. Diseases can cause temporary or permanent loss of our olfactory abilities. Traumatic brain injuries can lead to similar outcomes. Without your sense of smell, a condition called anosmia, there are dangers that can occur if you are home, for example, and cannot detect the smell of a gas leak. Without your sense of smell, you also lose your sense of taste. The tongue has limited taste receptors (sweet, sour, hot and cold) but without the nose working, odours draw a blank. A year ago, we hired painters to redo our apartment. One of them told us he got COVID-19 and lost his sense of smell. He had yet to get it back. To him, food tasted like metal or garbage.

How A Neuroprosthetic Works

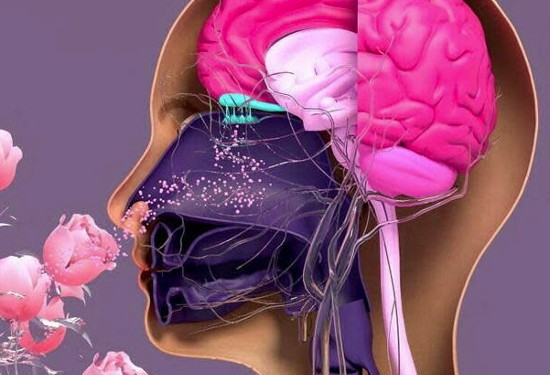

In the presence of an odour, one of hundreds of sensors in the neuroprosthetic recognizes a distinct smell and transmits the signal to an implant linked directly to the olfactory bulb of our brain which is responsible for identifying odours. The prosthetic works similarly to cochlear and retinal implants, devices used to restore hearing and sight.

The neuroprosthetic has to be a pretty complex device to come close to matching our noses. The 400 or so receptors we naturally have in our noses distinguish one trillion different smells. When a smell converted to an electrical signal reaches our olfactory bulb its sets off other brain interactions triggering mood, memory, and cognition. Smells bring back childhood memories. Smells can even be used therapeutically to overcome post-traumatic stress.

The Current State of Odour Detectors

Commercial and industrial odour sensors are specific. For example, we have in our apartment smoke and carbon monoxide detectors. Homes may have detectors for natural gas leaks, or radon gas leaking into basements. A detector, however, that can discriminate among these limited number of odours doesn’t exist at present. That’s why we have three or four. Creating a form factor that contains multiple sensors is both an engineering and size problem. So imagine trying to build a neuroprosthetic that detects not four by forty or four hundred different smells.

Where the VCU Team Is At

In experiments using rats as subjects so far, the VCU researchers have demonstrated they can create odour maps when areas of the olfactory bulb are stimulated. Working with human subjects is on the agenda with plans for a first-generation device to detect and differentiate dozens of smells. The device would incorporate several hundred microsensors. The VCU team is even talking about creating specialty neuroprosthetics to detect particular smells, for example, an e-nose for bakers or one for hikers to differentiate the smells of the forest.

Recently an article appeared in IEEE Spectrum describing the work being done at VCU and in other universities tackling the loss of sense of smell, largely being driven by the growing number of Long COVID sufferers. States Costanzo, “It’s a long process to make a device and get it to the point where you can safely implant it in patients…But the scientific part of it has moved very nicely. We laid the groundwork with injury and repair research, and after studying it for 40 years, have finally come up with something that might actually work.” When? He predicts within ten to fifteen years.