The pandemic that has embraced our entire planet for the last 18 months is being mitigated by a profusion of vaccines and the ramping up of production and distribution of them to get into peoples’ arms. But as we noted in Part 1 of this three-part series, we have a long way to go before we can create global immunity.

One of the challenges is evolution. Viruses evolve and because they exist in such large numbers, as they replicate, genetic instructions experience modifications. An RNA string mutates leading to a change in the virus. With the potential of hundreds of millions of hosts, the chances of mutations rise. So what starts off as COVID-19 becomes many COVID-19 variants. The World Health Organization (WHO) has created a video that explains how new variants get created.

From the beginning of the pandemic, virologists have expected variants. The first two deemed Alpha and Beta were first recognized in the United Kingdom and South Africa respectively. Both variants proved to be more transmissible than the original.

Since then we have seen Gamma emerge in Brazil and spread to 37 countries. And Gamma has evolved to create new mutations within Brazil itself, with a recent outbreak of the new variant in Manaus, the largest city on the Amazon River and a transportation hub.

Then there is Eta which first showed up in the United Kingdom and is now in 11 other countries including Australia, Canada, Denmark, Ghana, and the U.S.

Then there is Theta which first emerged in The Philippines, Iota and Epsilon in the U.S., and Lambda in Peru.

And now there is Delta and Kappa, both first identified in India and the leading cause of an enormous spike in cases and deaths in that country. Since Delta’s appearance, it has been detected in more than 60 other countries including the United Kingdom, U.S., Israel, Canada, and Singapore where it is proving to be the most virulent to date. In India, Delta has been associated with a spike in outbreaks of gangrene.

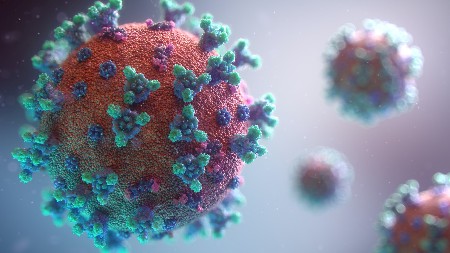

With every mutation of COVID-19, changes occur to the spikes that coat the exterior casing of the virus. It is these spikes, which are proteins, that attach to target cells and find their way inside.

So far there have been 23 mutations in the virus since it first emerged from Wuhan in late 2019. You can track the ongoing evolution of the variants, visit the WHO website.

The vaccines developed to date are built around creating inert versions of these spike proteins so that when ingested into a healthy cell, start the production of antibodies which then protect us from the virus. But if the mutated proteins are too much of a significant departure from those contained within the vaccines, the ability to protect people from infections is dramatically diminished.

Currently, two doses of the Pfizer-BionTech vaccine are proving to be 88% effective. That compares to the Alpha variant where the vaccine had been 93% effective in the United Kingdom before Delta showed up. Other vaccines have also seen their efficacy diminish with Delta and other variants, but not to the point where those who are vaccinated face hospitalization, or worse.

The WHO continues to track mutations and vaccines and therapies being used to deal with the evolving virus. But the most effective measures to stop variants from appearing remain the practices we have been asked to implement since the pandemic started: frequent hand washing, wearing a mask when indoors, social distancing whether in or outdoors, avoiding crowds, and ensuring good interior ventilation. The virus will not mutate if it can’t spread to new hosts.