SpaceX has yet to demonstrate that Starship will work in NASA’s Artemis Program aimed at returning humans to the Moon’s surface for the long term. NASA has built its Space Launch System (SLS) and the Orion capsule to deliver crews to orbit the Moon. The SLS is technology that harkens back to the days of the Apollo Program and has been beset by cost overruns and delays setting back the return to the Moon timetable several years.

The SpaceX Starship has been made an integral part of the Artemis Program. It too is behind schedule which is not uncommon for the development of this type of technology. SpaceX builds and breaks to learn what works and what doesn’t. It is an iterative process that is different from NASA’s process.

Three demonstration flights of the SpaceX Starship are a case in point. Starship has yet to meet the challenge of becoming a reliable technology for getting to space and back. The latest flight was in March 2024. A Starship along with its Super Heavy booster performed nominally during launch and through separation. The Starship made it to space and orbit. In the end, however, the Super Heavy, designed to be reusable, failed at a controlled descent. Starship, as well, had problems during its re-entry and descent into the Indian Ocean. SpaceX noted that some things worked well and acknowledged some didn’t.

One that appears to have worked is a critical requirement for the Artemis Program in its effort to develop space infrastructure to support future lunar habitability. NASA’s agenda includes the building of a gas station in space. This would be a place or means for a spaceship to refuel.

Refuelling a car here on Earth is pretty simple. We take it for granted. That’s because the technology is well established with infrastructure and supply lines in place. What appears routine here on the ground doesn’t exist in space. Refuelling there is more complicated. NASA calls the fuel transfer technology it wants in place, On-orbit Cryogenic Fluid Management or CFM.

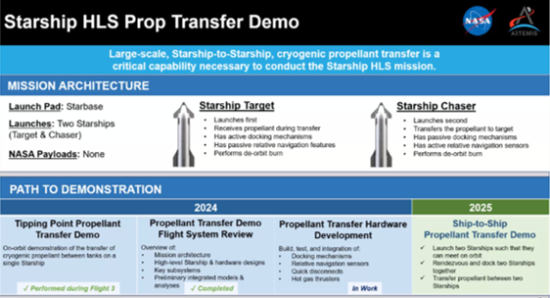

SpaceX was awarded the contract to demonstrate CFM in 2020. In this last Starship test flight, an intertank transfer was performed in orbit. The demonstration moved 10 tons of liquid oxygen from one tank to another on the Starship. This needs to be repeated using two Starships in a future mission planned for 2025. It will involve a rendezvous and docking of two Starships, a fuel transfer, and then a deorbit of both spaceships to land on Earth.

The March demonstration showed liquid propellant can be moved between two tanks in one ship, but not between two. Artemis will need CFM transfers that do the latter and handle numerous challenges including:

- Slosh – managing irregular movements of liquid during transfers.

- Ullage – dealing with tank volume changes and the partial emptying of them during transfers.

- Boiloff – controlling vaporization that occurs during fuel transfers, something seen when a rocket is fuelled before launch.

- Leaking – potential volatility from fuel leaks that could occur during transfers and their effects on orbital stability.

The Artemis 3 mission depends on CFM being successful. A version of the Starship called the Human Landing System (HLS) is to be fuelled this way during a demonstration flight to the Moon currently scheduled for late 2026. An uncrewed HLS will be fuelled in low-Earth orbit and then sent to the Moon where it will land and launch proving the technology works.

Artemis 3 will launch on the SLS with Orion and an astronaut crew on board. Orion will rendezvous with the HLS in lunar orbit before taking the lander to the Moon’s surface for a one-week stay before using the lander to get back to the Orion.

As Starship launches more demonstration flights, no doubt, SpaceX will repeat the intertank transfer demonstration to refine the performance of the technology. These future launches will correct performance defects from previous flights. The iterative process SpaceX uses is different than how NASA developed Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and the Space Shuttle. It has taken those who watch the pursuit of space some getting used to, but if the Falcon 9’s success is any measure of validation, the methodology appears to work.