May 3, 2017 – In our modern consumer society, we have trouble discerning fact from fiction in the face of clever marketing campaigns. One of the most unfortunate gimmicks of the North American food industry are the following messages printed on the things we eat each week. These messages include:

- “Best before”

- “Sell by”

- “Use by”

- “Expires by”

These instructions encourage food vendors and consumers to toss perfectly viable product in dumpsters, compost bins, and the garbage.

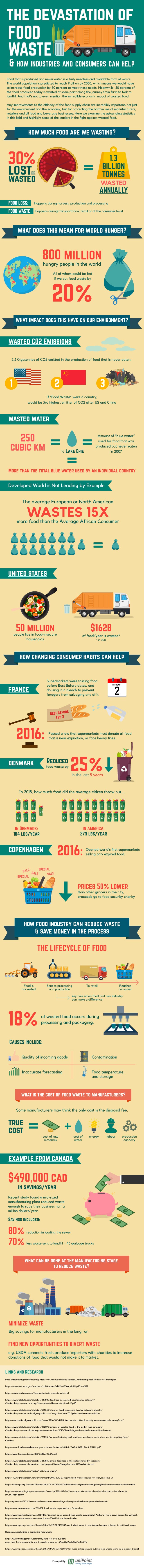

Back in December of 2015 I wrote that “we humans waste 1.3 billion tons of food every year.” The worst offenders at the consumer level live in Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand. Retailers uniformly contribute to food waste through improper refrigeration, bottlenecks in supply chains, importing food that can be locally produced and sourced, and poor stock rotation practices. And in the Developing World, the problems of wastage pervade the entire food chain from the field, to harvest, to post-harvest storage, to shipment, to retail, and finally to the consumer.

At the non-profit foundation website of ReFED, it describes the “patchwork of state regulations around date labeling….that leads to 20% of consumer waste of safe, edible food.” In the United States, because of this confusing patchwork, a law entitled, the Food Date Labeling Act of 2016 was introduced in Congress to create standardized messaging for all food manufacturers. The act proposed only two labels should be put on food, one to indicate quality, “best if used by,” and the other safety, “expires on.” The act also called for educating consumers about date labels, and about what could be done with food past its quality date. Unfortunately, the act never passed in either the House of Representatives or Senate and is not the law of the land.

Today in the United States, consumers throw out perfectly good food to the tune of $30 billion annually because of “sell by” and “best by” date stamps. How did this come about? It goes back to Europe where Marks & Spencer’s began using the two criteria in the 1950s in warehousing operations and later introduced it on in store shelves to consumers in 1970. Open dating started appearing on North American products soon thereafter, voluntarily adopted by supermarkets. So instead of the sniff test to determine if food was fresh, consumers became hooked on date stamps.

The end result in the 21st century has been an explosion in food waste. In a study published in July of 2016, entitled, “Household Food Waste: Multivariate Regression and Principal Components Analyses of Awareness and Attitudes among U.S. Consumers,” the authors write in the introduction, “About one-third of the world’s edible food is lost or wasted annually, while the challenge to feed the projected world population of 9.3 billion people by the mid-century will require 60% more food than is currently produced.” Consumer food waste awareness, state the authors, has been built on a false premise that food after an expiry date may cause illness, or minimally not taste fresh.

In 2015 President Obama acknowledged that food waste in a country where 42 million Americans went to bed hungry each night, was unconscionable. At the same time, he referenced the contribution that food waste was making to global warming. To date, 95% of the food thrown out by U.S. consumers goes into landfill, a primary source of greenhouse gasses. And to add insult to injury, the average American family of four throws away between $1,365 and $2,275 in food annually. Knowing this the President announced a goal of reducing food waste in the country by 50% by 2030.

The problem of food waste, of course, is not limited to the United States. One of my readers, Rebecca Hill, was kind enough to do her own research and created a visual reference that appears below. It includes useful links to research on the issue. Kudos to Rebecca for creating this excellent infographic.

For the rest of us who are still addicted to the “sell by” and “best before” labeling of food, we need to recognize that our eyes and noses are a better indicator of food freshness than any date stamp. In doing so we may waste less, help feed more of the hungry and reduce our contribution to undesirable climate change.