July 14, 2017 – For those of us who read this blog and live in North America, depleting aquifers is not a new subject. The Central Valley of California, the agriculture epicenter for almost half of all produce grown in the United States, because of recent drought and overuse of groundwater, faces a very iffy future. The Great Plains breadbasket of America is similarly challenged because of excessive drawing of water from the Ogallala aquifer. These water sources are tens of thousands of years old and replenishing them is not something we humans can do easily. We have to rely on natural processes and not our ingenious interventions.

A similar and even more dire situation exists in the food producing regions of the Indian Subcontinent. Both India and Pakistan have been pumping water out of the ground at record levels to irrigate the South Asian breadbasket.

In a 2010 paper written by Sushil Gupta and Sanjay Marwaha, presented at the International Conference on Transboundary Aquifers, the researchers write that “ground water is a fugitive resource,” that they “extend hydrological interdependence across national frontiers” and that “managing that interdependence is one of the great human development challenges facing the international community.”

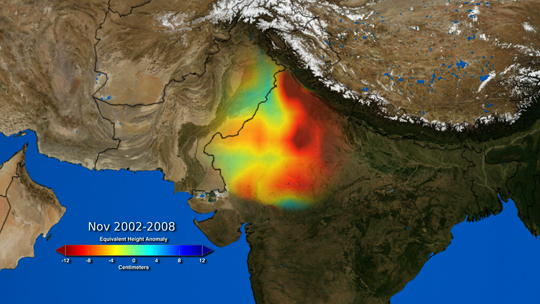

For India and Pakistan, sharing a common resource is particularly challenging. These countries remain at odds over a number of geopolitical issues and have fought several wars in the post-colonial era. Now the Punjab, an area that straddles the border between the two countries, containing a significant underground aquifer, is in danger of turning into a desert within two decades.

In 2016 the Union Ministry of Water Resources in India instituted a study to map the aquifer to a depth of 300 meters (1,000 feet). The Central Ground Water Board was to have completed it by March of this year but as of yet has not reported its findings. Meanwhile, India continues to deplete its groundwater sources at record levels.

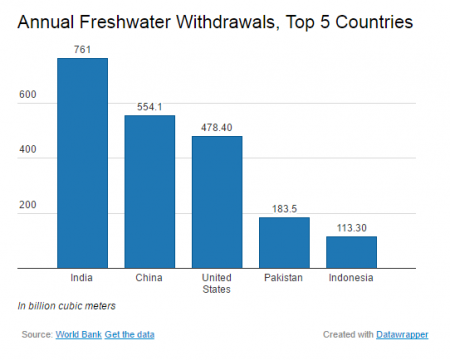

In 2016 India’s amount totaled 761 billion cubic meters, a rate 37% greater than China, and 59% greater than groundwater withdrawals in the United States. The result, India reports only 35% of monitored wells indicate water levels rising or the same, while the remaining balance of wells are in steep decline with drop rates in Punjab of 2 meters (7 feet) annually.

For Pakistan, which shares the Punjab Aquifer and in 2016 reported annual freshwater withdrawals of 183 billion cubic meters, the hydrological interdependence with its neighbour is slowly turning into a nightmare.

The Punjab in many ways resembles the Great Plains in the United States. It is defined as a semi-arid climate. The aquifer resource beneath it has turned it into the most intensively irrigated land on Earth just as the Ogallala has in the U.S. In the summer the crop is rice. In the winter it is wheat. And the two countries with a combined population of more than 1.5 billion overdraws the resource and uses wasteful irrigation practices. Meanwhile, the governments of both countries provide little in the way of disincentives to stop their respective farmers from excessive water consumption.

India is making some attempts in the Punjab to mitigate the future crisis. It has begun experimenting with recharge systems designed to channel surface water into wells and thus replenish the aquifer. In addition, the government is implementing educational programs to teach farmers how to create pond reservoirs from which they can irrigate their fields. But the water table continues to drop and climate change within the next two decades will only exacerbate the challenges.

Today, other than the aquifer, much of Punjab’s water comes from Himalayan glaciers and snowmelt and the annual monsoon. Global warming is likely to alter these climatological patterns. We may temporarily see an increase in surface water resources as glaciers melt faster. But on the other hand snowpacks may thin offsetting glacial melt. And the monsoon may become less reliable. So no one knows for sure what the state of surface or groundwater will be in the breadbasket of these two countries in 30 or 40 years from now.

That’s not a good situation for two countries perilously close to not meeting the food needs of their respective populations. And considering the fractious nature of the history between them, we may see future wars provoked by water woes, and not just by religion and shared history.

There are answers. India and Pakistan can explore using genetically modified drought tolerant rice. wheat, corn and soybeans. Or the two countries can switch to entirely different crops able to grow in increasingly arid conditions. The list includes chickpeas, lentils, beans, millet, and sorghum. All are protein rich and nutritionally dense. They can also consider mixed agricultural strategies rather than planting single crops. That way if one staple fails, the other surviving plants will thrive.