The world’s first commercially operating Direct-Air-Carbon-Capture (DAC) facility in Iceland has turned carbon dioxide (CO2) into stone. Nothing like it has been seen since the biblical Sodom and Gomorrah.

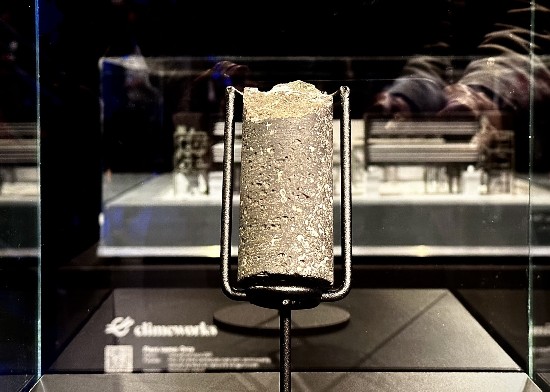

The last week at Climeworks’ DAC Summit in Switzerland, a lump of gray rock was on display, a sample of what this technology can produce to remove carbon from the atmosphere. But before too many raise their hands and shout hosannas, for DAC to make an appreciable dent in the CO2 emitted by us annually, we will need thousands of these facilities.

Right now the International Energy Agency (IEA) reports that there are 18 DAC plants in operation. Yet DAC technology has been around for a while. Back in 2015, I wrote about Carbon Engineering, a Calgary, Alberta-based startup with a pilot DAC plant demonstrating the removal of CO2 from ambient air. Since then pilot plants using similar technologies have cropped up in a few countries.

Beyond the 18 operational DAC plants, there are 11 in advanced development. If these come online before 2030, it will mean DAC capacity will grow to 5.5 Megatons. This is 700 times the current carbon capture rate and a mere fraction of what is needed to bend the carbon curve downward. But 18 and even 29 are woefully small numbers if we intend to remove a gigaton of carbon from the atmosphere annually as needed between now and 2030 according to the IEA. The plant in Iceland that was praised at the conference in Switzerland can capture a mere 4,000 tons of carbon dioxide and turn it into stone annually.

What has been holding DAC back?

The technology to direct-air-capture carbon dioxide has been known for some time. The cost per captured ton was seen as a barrier to market entry. Then there was the lack of carbon pollution pricing to offset the cost of implementing DAC. In 2007, the Province of Quebec was the first jurisdiction in Canada to put a price on carbon. In the same year, Alberta priced carbon emissions from fossil fuel and power generation operations. British Columbia followed in 2008 creating carbon pricing, a strategy that became the model for Canada’s future national carbon price which began at $10 CDN (approximately $7.50 US) per emitted ton in 2018. Annual increases have raised the price to $65 CDN (approximately $49 US), and it will continue to rise annually until it reaches $170 (approximately $128 US) by 2030.

Elsewhere, in the United States, California instituted a carbon market in 2012 which in 2022 set the price of carbon credits at $29 US per ton. The European Union’s carbon market currently puts a high price on carbon pollution at €89.9 ($98 US). Earlier this year the price briefly surpassed €100 ($109 US).

DAC facilities’ costs to capture carbon currently range from $125 to $335 USD per ton. So removing carbon from operations remains at best marginal and at worst wildly uneconomic. Right now unless governments are willing to chip in with large subsidies or tax breaks. there is little likelihood that polluters will adopt DAC widely.

Some encouraging news recently has one Texas-based fossil fuel energy provider planning to build and deploy 70 to 135 DAC plants between now and 2035. But where is everybody else?

At the conference in Switzerland last week, the stone from captured carbon had many in attendance giddy. Some described the atmosphere as celebratory. All that remained stated attendees now was to get the cost of deployment and operations down followed by massive deployment to save the planet.

Here too, governments need to change their act by speeding up approval processes for DAC deployment. The Holy Grail for carbon capture technology is to get to $100 per ton. Current industry experts believe a rapid build-out between now and 2030 could drop the cost per ton of captured carbon to that Holy Grail amount. If that were the case, the 2030 Canadian carbon levy at $128 US would make the building of more of these facilities far more attractive.