Some scientists call the warming of permafrost, the so-called permanently frozen subterranean world that stretches across Alaska, Northern Canada, Scandinavia, and Russia, a time bomb that will release vast amounts of methane (CH4) as early as mid-century. Others hypothesize that the CH4 leaks will ooze constantly over the remainder of this century and beyond because of warming in the atmosphere and the ocean near the pole.

Whether a slow ooze or a bomb, the question I ask in the title of this posting has yet to be answered by government policymakers. Is permafrost included in carbon budget calculations? My guess is, it is not and that’s a huge mistake.

Canada’s Answer to the Permafrost Challenge

The northern community of Tuktoyaktuk is built on top of permafrost and located on the Arctic Ocean coastline of Canada’s Northwest Territories. Permafrost is described as being harder than concrete in its frozen state. But when warmed the subsurface thawing causes landscapes to shift. Houses and buildings begin to tilt precariously as concrete and wooden pilings give way. A more ice-free Arctic Ocean is a more active sea with winds driving waves onshore contributing to growing coastal erosion. This in combination with rising sea levels is nibbling away at Tuktoyaktuk.

A September 2021 report noted that the cost to save Tuktoyaktuk was $42 million and rising. This money is budgeted to cover the next thirty years. The plan involves shoring up the Arctic Ocean coastline with a barrier of stone very much the way it is done on Pacific and Atlantic Ocean coastlines further south. Everyone knows this is a temporary fix. No one has a long-term plan that might require a retreat from the coastline and a movement of the town to a more stable inland site where only permafrost melt would be the threat.

What’s wrong with the stone barrier plan? There isn’t a lot of rock to harvest locally near Tuktoyaktuk which means hauling rock in from further inland and south over a road infrastructure that is also threatened by permafrost melt.

Of course, none of these plans speaks to the issue of CH4 release from melting permafrost and the contribution this greenhouse gas (GHG) will make to atmospheric warming in the short term.

Canada has a CH4 leak strategy. Unfortunately, it focuses entirely on CH4 emissions from fossil fuel sites. The following words come directly from a September 23, 2022 government policy statement that notes the country will:

- Implement measures across sectors of the economy, including oil and gas, to reduce the largest sources of methane emissions;

- Strengthen the clean technology sector and provide tools to industry to achieve cost-effective methane emission reductions while creating good-paying jobs;

- Advance scientific knowledge and technical capacity to improve methane detection, measurement, and reporting;

- Meet international climate targets under the Paris Agreement and Global Methane Pledge; and

- Solidify its global leadership and provide funding, tools, and best practices for other countries to achieve emissions reductions.

Notice, there is no mention of permafrost CH4 leaks in this policy statement. Yet another government site discusses the issue of Arctic melting and notes that “Canadian scientists and community members have long raised concerns about how rapid climate change affects permafrost in Northern Arctic communities.”

The page comes with a link to a report that raises alarm bells about the amount of GHGs contained within an increasingly destabilizing permafrost zone across the country’s north. It also discusses other issues related to melting permafrost including increasing coastal erosion, ground subsidence, landslides, altered surface water dynamics (kettle lakes vanishing overnight), damage to buildings, roads, power distribution networks and more, and a growing number of health risks.

- Melting permafrost will release mercury and other heavy metals that have built up over millennia. These metals will enter the food chain and impact wildlife and human health.

- Municipal and industrial waste that has been stored in landfills in the permafrost as they thaw will begin to leak chemicals and biological materials into surrounding environments posing further health challenges.

Recommendations include the implementation and budgeting for:

- Sustainable coastline mitigation strategies.

- Redesigning infrastructure to accommodate changing conditions in permafrost.

- Better scientific and engineering monitoring of permafrost zones to get a handle on actual changes going on with an ability to forecast the future.

- Design reclamation strategies to deal with chemical and metal contaminants, and waste disposal.

Also recommended is a better use of the knowledge gained from local and native observations that can serve to advance strategies and provide solutions to contain the worst of anticipated future damages to the Arctic way of life. Unfortunately, there appears to be no budget estimate to finance the above recommendations and nothing on the website to suggest Canada’s Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change has a specific one in mind to underwrite the cost of implementing these recommendations.

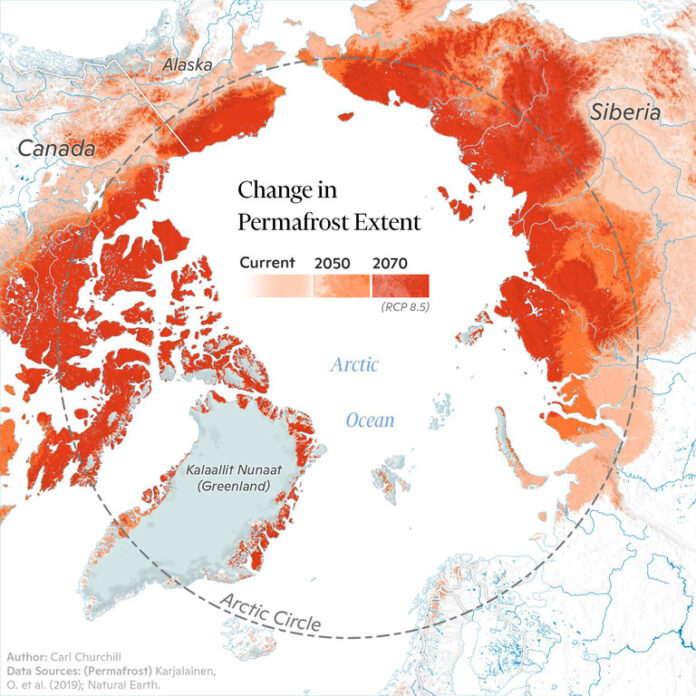

[…] map featured at the top of Part One tells you why. Southern permafrost boundaries were seen to be moving poleward decade by decade over […]