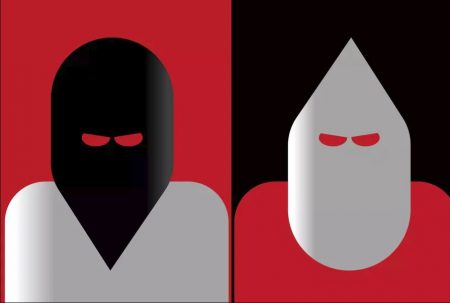

April 24, 2019 – Using violence against public targets seems to be the present fashion of terrorist groups whether jihadists, religious extremists, white supremacists, fascists, militants, armed militias, and other disparate action groups that believe violence gives them a voice. This is nothing new to the human experience, but in the 21st-century accessibility to those amenable to extremist messages is creating a growing population prepared to be cannon fodder for militant causes.

I remember the morning of September 11, 2001, when while driving back from a physiotherapy session I first heard the news on the radio about an airplane hitting the first of the two towers in New York City. I ran into the house and turned on CNN and watched a correspondent talking to the television audience while behind him another airplane struck the second tower. I knew people who worked in those two buildings and spent much of the morning on the telephone talking to people in the United States who also had acquaintances and friends working there. In the face of such violent acts, all I could feel was helplessness.

Post 9/11 we seem to live in a world that has come to expect acts of terror whether carried out on the streets of Paris, the Christmas market in Strasbourg, and in churches on an Easter Sunday in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Terrorism in 1914 came with a bullet and led to the start of World War One. Contrived terror in Germany fed by Nazis conspirators led to fascist Germany and World War Two. But since then when acts of terror have occurred they have largely been confined to intractable conflicts such as Israel and its Palestinian and Arab neighbours, Northern Ireland, Kashmir, Mumbai, and civil wars within countries from Asia, to Africa, Central, and South America.

Past acts of terror if they victimized more than 10 people were extremely rare before 1988 the year when a Pan Am 747 was blown up by an onboard bomb over Lockerbie, Scotland killing all 243 passengers, 16 crew, and 11 on the ground. It seems since then that the scale of political terror aimed at civilians has grown to create as many deaths as possible through single acts of violence. And that violence has created new kinds of warriors outfitted in suicide vests who are prepared to martyr themselves as did occur in Sri Lanka this last weekend.

In the United States where the gun is king, acts of mass murder occur weekly with those who are perpetrators often loners, and more often white and male. Guns with semi-automatic features are the weapons of choice.

But for jihadists, the scale is much greater. Whether turning an airplane into a bomb to kill more than 3,000 or seeking even more powerful weapons of mass destruction, terrorism in the 21st century is all about increasing the scale of the killing.

What seems to be common to those who seek violence in the name of their causes, is some kind of ritual purification that comes with the act, some perverse sense of heroism associated with bomb throwing, or self-immolation while wearing a suicide vest. It is no wonder that those who are terrorists often have a strong sense of identity with a religious or ethnic cause.

This isn’t new stuff. After all the Crusades were a series of conflicts spanning more than two centuries inspired by the Catholic Church. Jihadism was an element of Islam’s birth as the faith spread by fire and sword expanded from its Arabian base to claim North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia.

But what is new is the damage that small, intensely hateful social groups can, through an interconnected world find like-minded individuals to organize and carry out acts of extreme violence against so many with nihilistic intent.

Walter Laqueur and Christopher Wall, in their recently published book, “The Future of Terrorism,” with the subtitle “ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and the Alt-Right” describe modern terrorist acts as the fetishizing of violence. In other words, it is in violence that these groups find their purpose, driven by hate, inspired by a cause, and prepared to be heroes to it.

What can society do in the face of terrorism’s ability to scale in our technologically enhanced 21st-century world?

We cannot allow civil society to become so obsessed with the fear of terrorist acts that we lose individual freedoms and increasingly live in a militaristic and armed camp. To put some perspective on the total impact of terrorism in terms of lives lost, a study appearing in “Our World in Data” shows that in 2010, terrorism accounted for 13,186 deaths globally.

Compared to childhood deaths before the age of five from illness, and malnutrition, amounting to more than 12 million in that same year, terrorism deaths amount to 0.1%.

Tobacco in 2011 killed 6 million, obesity, 2.8 million, and alcoholism, 2.5 million.

Air pollution in both indoor and outdoor kills millions every year.

In the world study, they don’t mention weather and climate change-related deaths which, as we know, is becoming an existential threat to the planet.

So if society wants to pick the right battles to win, there are many far more worthy than a war on terror which the West has embarked upon since 9/11. This neverending fight has drawn America and allies into conflicts and civil wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria, and elsewhere and has expended trillions of dollars without ending terrorist acts.

Richard Clarke, who worked at the National Security Council in the United States between 1992 and 2003, has talked about the U.S. involvement in Iraq as just one example of a failed policy, stating:

“Far from addressing the popular appeal of the enemy that attacked us [he is talking about 9/11], Bush handed that enemy precisely what it wanted and needed, proof that America was at war with Islam, that we were the new Crusaders come to occupy Muslim land.”

Even more perplexing is how technological innovation has made the ideology of terrorist groups widely available across the globe. The Internet, and social media today provide the means by which the propaganda of hate and violence is widely dispensed. Recruitment has become easy and costs little. Fundraising a cinch. Short of putting up virtual walls around Internet, and social media access as is being done in China, North Korea, and more recently in an experiment in Russia, it is impossible for us to block terrorist ideology and hate from audiences that feel the content appeals to them.

Has terrorism to-date succeeded in winning anything?

ISIS, the attempt to recreate a new iteration of Islam’s Caliphate no longer has a physical state although it remains a potent force for recruiting hate splinter groups to speak in its name or carry out isolated terror such as occurred in Sri Lanka. The Palestinian cause which was fuelled in its early stages by acts of terror has failed to achieve a nation-state. The Irish Republican Army even in the latest act of terror in its name has never reunited Ireland. The terrorist attacks in Paris, Germany, and other European countries have not overthrown governments.

What terrorist acts from extremist groups have done is unsettle us and make us expend a great deal of capital with little effect. We have given them what they seek, notoriety. And we have given them the global stage which has to end.

The more serious threat that can hurt far more of us lies in state-sponsored acts such as penetration of public and private networks that manage national infrastructure, communications, banks, government, the military, and that disrupt free elections. This is the terror that requires governments, business organizations, and citizens to be more cognizant and vigilant, particularly in the age of the Internet.