When Elon Musk on stage in 2013 demonstrated how quickly one of his Model S sedans could swap out and replace a battery, it seemed like this was an opportunity to boost electric vehicle (EV) adoption. If the owner purchased a Tesla and subscribed to a battery service, the price of each vehicle would come way down. At the time Musk stated “hopefully this is what convinces people finally that electric cars are the future.” But the idea shortly died.

Now it is being revived as various EV makers and service providers are looking at it as a new business model called battery-as-a-service (BaaS). The idea of separating ownership of the car from the battery could prove to be the key accelerator to rapid adoption and the electrification of road transportation globally.

So who is doing it?

China for one where a number of its EV manufacturers see swappable batteries as an alternative or supplement to EV charger infrastructure. It also can overcome range anxiety issues if an EV owner can pop into a BaaS service centre and keep going a few minutes later with a full charge.

In May 2021, China approved a national swappable EV battery standard seeing it as a way to increase adoption, reduce vehicle costs, and provide an ample inventory of batteries that could be charged in off-peak periods and be made available to customers. BaaS could prove to be a cheaper charging service if done off-peak and EV owners could choose the size and range of battery needed when doing the swap. Chinese EV manufacturers Nio, Baic and Geely are backing the new standard with the latter recently demonstrating a 1-minute swap in a YouTube video.

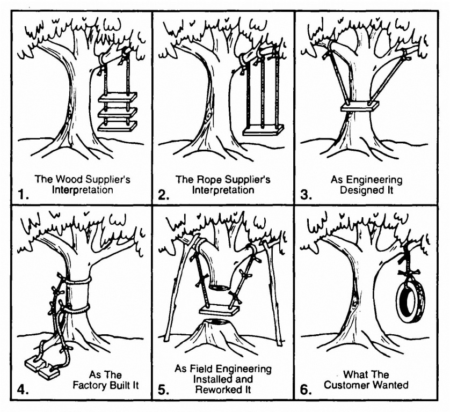

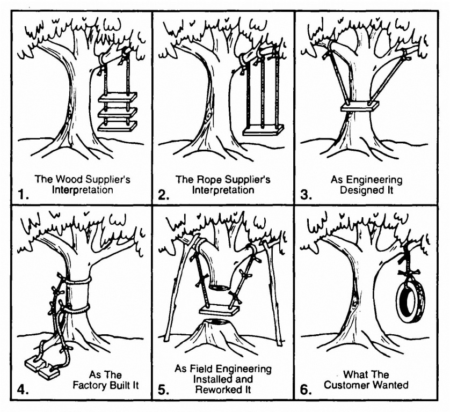

A recent IEEE Spectrum article describes battery swapping in 2021 as particularly bad, calling it a Rube Goldberg notion. The term Rube Goldberg refers to over-engineered solutions to simple problems. I’m always reminded of the comic that shows a backyard tire swing and what Rube Goldberg experts proposed as a solution.

But is the idea of BaaS truly a Rube Goldberg solution? The IEEE article describes how Nio’s BaaS is working and it certainly doesn’t sound like a fix to a non-problem. Nio cars bought with a battery swap subscription are being priced $10,000 US lower. The purchaser buys a $142 monthly lease which entitles him or her to a 70 Kilowatt-hour battery pack and six swaps a month. In April of this year, Nio reported 2 million total swaps and calculated it had extended the average EV range by approximately 200 kilometres (123 miles) through the swaps.

But is the idea of BaaS truly a Rube Goldberg solution? The IEEE article describes how Nio’s BaaS is working and it certainly doesn’t sound like a fix to a non-problem. Nio cars bought with a battery swap subscription are being priced $10,000 US lower. The purchaser buys a $142 monthly lease which entitles him or her to a 70 Kilowatt-hour battery pack and six swaps a month. In April of this year, Nio reported 2 million total swaps and calculated it had extended the average EV range by approximately 200 kilometres (123 miles) through the swaps.

What are the issues the IEEE article is raising? It argues that the battery range in new EVs well exceeds 200 kilometres today. And a growing EV fast-charging network is becoming a reality allowing operators to top up a battery in 20 to 30 minutes, or as the article states, in the time it would take to do a bathroom break and get a cup of coffee.

I question that argument as sufficient to warrant not implementing BaaS, particularly in urban settings. For city drivers looking at an EV solution, a 1, 5 or 10-minute battery swap that extends driving range greater than the average daily commute, while lowering the purchase or lease vehicle price, makes considerable sense.

That may be one of the motives behind San Francisco-based, Ample, a start-up that wants to make battery swapping ubiquitous in the U.S. Ample has opened five battery-swapping outlets in San Francisco with its first customer, Uber. Uber is using Nissan Leafs in the city. Ample keeps a supply of batteries on hand for these models as well as for some made by Kia. Ample believes EV fleet managers are a good target audience for BaaS particularly because the operation of a driving service puts a great deal of wear and tear on EV batteries frequently requiring recharges and logging hundreds of kilometres per daily shift.

The counter argument says BaaS is a headache because the batteries would have to be stored for a variety of models, a logistical nightmare for supply and distribution. The batteries would require continuous maintenance and would have to be kept charged at all times. The environmental impact in wasteful use of electricity and the potential for adding carbon emissions, plus them lying around waiting for customers presents a chaotic scene. And then there is the recycling of spent batteries.

Ample’s answer is to standardize around a limited number of models and keep a focus on fleet operators. The company intends to remove and recharge batteries in off-peak hours and source the energy from renewable providers. It believes its practices will help fleet operators get longer life from their EVs, achieve their carbon reduction goals and save on electricity bills.

The market appears to be responding positively to these new EV business models. Ample has raised $68 million US in venture capital from a fund in which Shell is a partner. And Nio is getting lots of interest in its initiative with shares increasing in value by more than 1,000% in the last year.